activityopendns

opendns 时间:2021-05-20 阅读:()

TowardsaModelofDNSClientBehaviorKyleSchomp,MichaelRabinovich,MarkAllmanCaseWesternReserveUniversity,Cleveland,OH,USAInternationalComputerScienceInstitute,Berkeley,CA,USAAbstract.

TheDomainNameSystem(DNS)isacriticalcomponentoftheInternetinfrastructureasitmapshuman-readablehostnamesintotheIPaddressesthenetworkusestoroutetrac.

Yet,theDNSbehaviorofindividualclientsisnotwellunderstood.

Inthispaper,wepresentacharacterizationofDNSclientswithaneyetowardsdevelopingananalyticalmodelofclientinteractionwiththelargerDNSecosystem.

WhilethisisinitialworkandwedonotarriveataDNSworkloadmodel,wehighlightavarietyofbehaviorsandcharacteristicsthatenhanceourmentalmodelsofhowDNSoperatesandmoveustowardsananalyticalmodelofclient-sideDNSoperation.

1IntroductionThemodernInternetreliesontheDomainNameSystem(DNS)fortwomainfunctions.

First,theDNSallowspeopletoleveragehuman-friendlyhostnames(e.

g.

,"www.

cnn.

com")insteadofobtuseIPaddressestoidentifyahost.

Second,hostnamesprovidealayerofabstractionsuchthattheIPaddressassignedtoahostnamecanvaryovertime.

Inparticular,ContentDistributionNetworks(CDNs)employthislatebindingtodirectuserstothebestcontentreplica.

PreviousworkshowsthatDNSlookupsprecedeover60%ofTCPconnections[14].

Asaresult,individualclientsissuelargenumbersofDNSqueries.

Yet,ourunderstandingofDNSquerystreamsislargelybasedonaggregatepopula-tionsofclients—e.

g.

,atanorganizational[6]orresidentiallevel[3]—leavingourknowledgeofindividualclientbehaviorlimited.

ThispaperrepresentsaninitialsteptowardsunderstandingindividualclientDNSbehavior.

WemonitorDNStransactionsbetweenapopulationofthousandsofclientsandtheirlocalresolversuchthatweareabletodirectlytielookupstoindividualclients.

OurultimategoalisananalyticalmodelofDNSclientbehaviorthatcanbeusedforeverythingfromworkloadgenerationtoresourceprovisioningtoanomalydetection.

InthispaperweprovideacharacterizationofDNSbehavioralongthedimensionsourmodelwillultimatelycoverandalsoanecdotallyshowpromisingmodelingapproaches.

Note,oneviewholdsthatDNSisa"sideservice"andshouldnotbedirectlymodeled,butrathercanbewellunderstoodbyderivingtheDNSworkloadfromapplicationssuchaswebbrowsingandemailtransmission.

However,derivingaDNSworkloadfromapplicationbehaviorisatbestdicultbecause(i)clientThisworkwasfundedinpartbyNSFgrantCNS-1213157.

cachingpoliciesimpactwhatDNSqueriesareactuallysentinresponsetoanapplicationevent,(ii)someapplicationsselectivelyusepre-fetchingtolookupnamesbeforetheyareneededand(iii)suchaderivationwouldentailunder-standingmanyapplicationstopulltogetherareasonableDNSworkload.

There-fore,wetaketheapproachthatfocusingontheDNStracitselfisthemosttractablewaytounderstand—andeventuallymodel—namelookups.

Tomotivatetheneedforamodel,weprovideanexemplarfromourpreviouswork.

In[14],weproposethatclientsshoulddirectlyresolvehostnamesinsteadofusingarecursiveresolver.

Ideally,anevaluationofthisendsystem-basedmech-anismwouldbeconductedinthecontextofendsystemsthemselves.

However,thebestdatawecouldobtainwasatthelevelofindividualhouseholds—whichweknowtoincludemultiplehostsbehindaNAT.

Therefore,theresultsofourtrace-drivensimulationsareatbestanapproximationoftheimpactofthemech-anismwewereinvestigating.

OurresultswouldhavebeenmoreprecisehadwebeenabletoleverageamodelofindividualclientDNSbehavior.

Broadly,theremainderofthispaperfollowsthecontoursofwhatamodelwouldcapture.

Werstfocusonunderstandingthenatureoftheclientsthem-selvesin§3,ndingthatwhilemostaretraditionaluser-facingdevices,thereareothersthatinteractwiththeDNSindistinctways.

Nextweobservein§4thatDNSqueriesoftenoccurclosely-spacedintime—e.

g.

,drivenbyloadingobjectsforasinglewebpagefromdisparateservers—andthereforewedevelopamethodtogathertogetherqueriesintoclusters.

Wethenassessthenumberandspacingofqueriesin§5andnallytacklethepatternsinwhathostnamesindividualclientslookupin§6.

Wendthatclientshavefairlydistinct"workingsets"ofnames,andalsothathostnamepopularityhaspowerlawproperties.

2DatasetOurdatasetcomesfromtwopackettapsatCaseWesternReserveUniversity(CWRU)thatmonitorthelinksconnectingthetwodatacentersthathouseallveoftheUniversity'sDNSresolvers—i.

e.

,betweenclientdevicesandtheirre-cursiveDNSresolvers.

WecollectfullpayloadpackettracesofallUDPtracinvolvingport53(thedefaultDNSport).

ThecampuswirelessnetworksituatesclientdevicesbehindNATsandthereforewecannotisolateDNStractoin-dividualclients.

Hence,wedonotconsiderthistracinourstudy(although,futureworkremainstobetterunderstandDNSusageonmobiledevices).

TheUniversityAcceptableUsePolicyprohibitstheuseofNATonitswirednetworkswhileoeringwirelessaccessthroughoutthecampus,andthereforewebelievethetracwecapturefromthewirednetworkdoesrepresentindividualclients.

OurdatasetincludesallDNStracfromtwoseparateweeksandispartitionedbyclientlocation—intheresidentialoroceportionsofthenetwork.

DetailsofthedatasetsaregiveninTable1includingthenumberofqueries,thenumberofclientsthatissuethosequeries,andthenumberofhostnamesqueried.

Validation:DuringtheFebruarydatacollection,wecollectquerylogsfromthevecampusDNSresolverstovalidateourdatasets1.

Comparingthepacket1Weprefertracesoverlogsduetothebettertimestampresolution(msecvs.

sec).

DatasetDatesQueriesClientsHostnamesFeb:ResidentialFeb.

26-Mar.

432.

5M1359(IPs)652KFeb:Residential(lter)Feb.

26-27,Mar.

2-416.

4M1262(MACs)505KFeb:Residential:Users15.

3M1033499KFeb:Residential:Others1.

11M2297.

94KFeb:OceFeb.

26-Mar.

4232M8770(IPs)1.

98MFeb:Oce(lter)Feb.

26-27,Mar.

2-4143M8690(MACs)1.

87MFeb:Oce:Users118M59861.

52MFeb:Oce:Others25.

0M2704158KJun:ResidentialJun.

23-Jun.

2911.

7M345(IPs)140KJun:Residential(lter)Jun.

23-26,296.

22M334(MACs)120KJun:Residential:Users5.

81M204116KJun:Residential:Others408K1304.

13KJun:OceJun.

23-Jun.

29245M8335(IPs)1.

61MJun:Oce(lter)Jun.

23-26,29133M8286(MACs)1.

52MJun:Oce:Users108M54951.

42MJun:Oce:Others25.

0M279163.

1KTable1.

Detailsofthedatasetsusedinthisstudy.

tracesandlogswenda0.

6%and1.

8%lossratesintheFeb:ResidentialandFeb:Ocedatasets,respectively.

Webelievetheselossesareanartifactofourmeasurementapparatusgiventhatthelossrateiscorrelatedwithtracvolume.

TrackingClients:Weaimtotrackindividualclientsinthefaceofdynamicaddressassignment.

SimultaneouslywiththeDNSpackettrace,wegatherlogsfromtheUniversity'sthreeDHCPservers.

Therefore,wecantrackDNSactivitybasedonMACaddresses.

Note,wecouldnotmap1.

3%ofthequeriesacrossourdatasetstoaMACaddressbecausethesourceIPaddressinthequeryneverappearsintheDHCPlogs.

TheselikelyrepresentstaticIPaddressallocations.

Further,withoutanyDHCPassignmentswearecondentthattheseIPsrepre-sentasinglehost.

FilteringDatasets:Wendtwoanomaliesthatskewthedatainwaysthatarenotindicativeofuserbehavior.

First,wendroughly25%ofthequeriesrequesttheTXTrecordfordebug.

opendns.

com.

(Thenextmostpopularrecordrepre-sentslessthan1%ofthelookups!

)Wendthisqueryisnotinresponsetousers'actions,butisautomaticallyissuedtodeterminewhethertheclientisusingtheOpenDNSresolver(indicatedintheanswer)[1].

Weobserve298clientsqueryingthisrecord,whichweassumeuseOpenDNSonothernetworksorusedOpenDNSinthepast.

Weremovethesequeriesfromfurtheranalysis.

Thesecondanomalyinvolves18clientswhoseprominentbehavioristoqueryfordebug.

opendns.

comandotherdomainsrepeatedlywithoutevidenceofaccomplishingmuchwork.

Thecampusinformationtechnologydepartmentveriedthattheseclientsserveanoperationalpurposeandarenotuser-facingdevices.

Therefore,weremovethe18clientsastheyarelikelyuniquetothisnetworkanddonotrepresentusers.

Wedonotattempttofurtherltermisbehavinghosts—e.

g.

,infectedormisconguredhosts—asweconsiderthempartoftheDNSworkload(e.

g.

,sincearesolverwouldberequiredtocopewiththeirrequests).

Timeframe:TomoredirectlycompareresidentialandocesettingsweexcludeSaturdayandSundayfromourdatasets.

Table1showsthemagnitudeofourltering.

Wendcommonalityacrossthepartitionsofthedata,sowefocusontheFeb:Residential:Usersdatasetforconcisenessanddiscusshowotherdatasetsdierasappropriate.

MarkerClients%All1262100%Googleanalytics98378%Searchengine101080%Google100680%Anyother60248%Gmail88170%LDAPLogin84066%Any103382%Table2.

Feb:Residentialclientsthattmarkersforgeneralpurposedevices.

3IdentifyingTypesofClientsSinceourfocusisoncharacterizinggeneralpurposeuser-facingdevices,weaimtoseparatethemfromothertypesofendsystems.

Weexpectgeneral-purposesys-temsareinvolvedintasks,suchas(i)webbrowsing,(ii)accessingsearchengines,(iii)usingemail,and(iv)conductinginstitutional-specictasks2.

Therefore,wedevelopthefollowingmarkerstoidentifygeneral-purposehosts:Browsing:AlargenumberofwebsitesembedGoogleAnalytics[8]intheirpages,thusthereisahighlikelihoodthatregularuserswillqueryforGoogleAnalyticshostnamesonoccasion.

Searching:WedetectwebsearchactivityviaDNSqueriesforthelargestsearchengines:Google,Yahoo,Bing,AOL,Ask,DuckDuckGo,Altavista,Baidu,Lycos,Excite,Naver,andYandex.

Email:CWRUusesGoogletomanagecampusemailandthereforeweusequeriesfor"mail.

google.

com"toindicateemailuse.

Institutional-SpecicTasks:CWRUusesasinglesign-onsystemforauthen-ticatingusersbeforetheyperformavarietyoftasksandthereforeweusequeriesforthecorrespondinghostnameasindicativeofuserbehavior.

Table2showsthebreakdownoftheclientsintheFeb:Residentialdataset.

Ofthe1,262clientsweidentify1,033asuser-facingbasedonatleastoneoftheabovemarkers.

Intuitivelyweexpectthatmultiplemarkerslikelyapplytomostgeneralpurposesystemsandinfactwendatleasttwomarkersapplyto991oftheclientsinourdataset.

Resultsforourotherdatasetsaresimilar.

Wenextturntothe229clients(≈18%)thatdonotmatchanyofourmark-ersforuser-facingclients.

TobetterunderstandtheseclientsweaggregatethembasedonthevendorportionoftheirMACaddresses.

First,wendasetofven-dorsandquerystreamsthatindicatespecial-purposedevices:(i)48Microsoftdevicesthatqueryfornameswithinthexboxlive.

comdomain,whichweconcludeareXboxgamingconsoles,(ii)33Sonydevicesthatqueryfornameswithintheplaystation.

netdomain,whichweconcludeareSonyPlaystationgamingcon-soles,(iii)16Appledevicesthathaveanaverageof11Kqueries—representing96%oftheirlookups—fortheapple.

comdomain,eventhoughtheaverageacrossalldevicesthatlookupanapple.

comnameis262queries,whichweconcludeareAppleTVdevicesand(iv)7Linksysdevicesthatissuequeriesfores-uds.

usatech.

com,whichweconcludearetransactionsystemsattachedtothelaundrymachinesintheresidencehalls(!

).

2Inourcase,thisiscampus-lifetasks,e.

g.

,checkingthecoursematerialsportal.

Inadditiontothese,wenddevicesthatwecannotpinpointexplicitly,butdonotinfactseemtobegeneral-purposeclientsystems.

Wend41DelldevicesthatdierfromthelargerpopulationofhostsinthattheyqueryformorePTRrecordsthanArecords.

Apotentialexplanationisthatthesedevicesareserversobtaininghostnamesforclientsthatconnecttothem(e.

g.

,aspartofsshd'svericationstepsortologclientconnects).

Wealsoidentify12KyoceradevicesthatissuequeriesforonlythecampusNTPandSMTPservers.

Weconcludethatthesearecopymachinesthatalsooeremailingofscanneddocuments.

FortheIPaddressesthatdonotappearintheDHCPlogs(i.

e.

,addressesstaticallyconguredonthehosts),wecannotobtainavendorID.

However,wenotethat97%ofthequeriesand96%oftheuniquedomainnamesfromthesemachinesinvolveCWRUdomainsandthereforeweconcludethattheyservesomeadministrativefunctionandarenotgeneralpurposeclients.

Theremaining61devicesaredistributedamong42hardwarevendors.

Intheremainderofthepaperwewillconsiderthegeneralpurposeclients(Users)andthespecialpurposeclients(Others)separately,aswedetailinTable1.

Wendthatourhigh-levelobservationsholdacrossalloftheUsersdatasets,andthuspresentresultsfortheFeb:Residential:Usersdatasetonly.

4QueryClustersApplicationsoftencallformultipleDNSqueriesinrapidsuccession—e.

g.

,aspartofloadingallobjectsonawebpage,orprefetchingnamesforlinksusersmayclick.

Inthissection,wequantifythisbehaviorusingtheDBSCANalgorithm[4]toconstructclustersofDNSqueriesthatlikelyshareanapplicationevent.

TheDBSCANalgorithmusestwoparameterstoformclusters:aminimumclustersizeMandadistanceεthatcontrolstheadditionofsamplestoacluster.

Weusetheabsolutedierenceinthequerytimestampsasthedistancemetric.

Ourrsttaskistochoosesuitableparameters.

Ourstrategyistostartwitharangeofparametersanddeterminewhetherthereisapointofconvergencewheretheresultsofclusteringdonotchangegreatlywiththeparameters.

Basedonthestrategyin[4],westartwithanMrangeof3–6andanεrangeof0.

5–5seconds—notethatM=2simpliestothresholdbasedclustering,butdoesnotproduceapointofconvergence.

Wendthat96%oftheclustersweidentifywithM=6areexactlyfoundwhenM=3andhenceatM=3wehaveconvergedonareasonablystableanswerwhichweuseinthesubsequentanalysis.

Additionally,wendthatforε∈[2.

5,5],thetotalnumberofclusters,thedistributionofclustersizes,andtheassignmentofqueriestoclustersremainsimilarirrespectiveofεvalueandthereforeuseε=2.

5secondsinouranalysis.

WedenetherstDNSqueryperclusterastherootandallsubsequentqueriesintheclusterasdependents.

IntheFeb:Residential:Usersdataset,wend1Mclustersthatencompass80%oftheroughly15Mqueriesinthedataset.

Tovalidatetheclusteringalgorithmwerstinspectthe67Kuniquehost-namesthealgorithmlabelsasnoise.

Wendavarietyofhostnameswiththemostfrequentbeing:WPAD[7]queriesfordiscoveringproxies,GoogleMailandGoogleDocs,softwareupdatepolling(e.

g.

,McAfeeandSymantec),heart-beatsignalsforgamingapplications(e.

g.

,Origin,Steam,Blizzard,Riot),videoFig.

1.

Numberofqueries,hostnames,andSLDspercluster.

Fig.

2.

Queriesissuedbyeachclientperday.

streaming(e.

g.

,Netix,YouTube,Twitch),andtheNetworkTimeProtocol(NTP).

AllofthesenamescanintuitivelycomefromapplicationsthatrequireonlysporadicDNSqueries,astheyareeithermakingquickcheckseveryonceinawhile,orareusinglong-livedsessionsthatleverageDNSonlywhenstarting.

Tovalidatetheclustersthemselves,weobservethattherearefrequentlyoc-curringroots.

Indeed,the1Mclustershaveonly72Kuniqueroots,withthe100mostfrequentlyoccurringrootsaccountingfor395K(40%)oftheclusters.

Fur-ther,the100mostpopularrootsincludepopularwebsites(e.

g.

,www.

facebook.

com,www.

google.

com).

Thesearethetypeofnameswewouldexpecttoberootsinthecontextofwebbrowsing.

Anothercommonrootissafebrowsing.

google.

com[9],ablacklistdirectoryusedbysomewebbrowserstodetermineifagivenwebsiteissafetoretrieve.

Thisisadistinctlydierenttypeofrootthanapopularwebsitebecausetherootisnotdirectlyrelatedtothedependentsbythepagecontent,butratherviaaprocessrunningontheclients.

ThisinsomesensemeansSafeBrowsing-basedclustershavetworoots.

WhileuseofSafeBrowsingisfairlycommoninourdataset,wedonotndadditionalprevalentcasesofthis"tworoots"phenomenon.

Fromamodelingstandpointwehavenotyetdeterminedwhether"tworoots"clusterswouldneedspecialtreatment.

Figure1showsthedistributionofqueriespercluster.

Whilethemajor-ityofclustersaresmall,therearerelativelyfewlargeclusters.

Wendthat90%ofclusterscontainatmost26queriesforatmost22hostnames.

Addi-tionally,wend90%oftheclustersencompassatmost10SLDs.

Thelargestclusterspans95secondsandconsistsof9,366queriesfornamesthatmatchtothe3rdlevellabel.

Thesecondlargestclusterconsistsof6,211queriesformyapps.

developer.

ubuntu.

com—whichislikelyaUbuntubug.

5QueryTimingNextwetacklethequestionofwhenandhowmanyqueriesclientsissue.

Webeginwiththedistributionoftheaveragenumberofqueriesthatclientsissueperday,Fig.

3.

Timebetweenqueriesfromthesameclientinaggregateandperclient.

Fig.

4.

Durationofclusters,inter-clusterquerytimeandintra-clusterquerytime.

asgiveninFigure2.

WendthatclientsinUsersissue2Klookupsperdayatthemedianand90%ofclientsinUsersissuelessthan6.

7Kqueriesperday.

TheOthersdatasetsshowgreatervariabilitywhererelativelyfewclientsgeneratethelion'sshareofqueries—i.

e.

,thetop5%ofclientsproduceroughlyasmanytotalDNSqueriesperdayasthebottom95%intheFeb:Residential:Othersdataset.

Arelatedmetricisthetimebetweensubsequentqueriesfromthesameclient,orinter-querytimes.

Figure3showsthedistributionoftheinter-querytimes.

The"Aggregate"lineshowsthedistributionacrossallclients.

Thearea"90%"showstherangewithinwhich90%oftheindividualclientinter-querytimedistributionsfall.

Themajorityofinter-querytimesareshort,with50%oflookupsoccurringwithin34millisecondsofthepreviousquery.

However,wealsondaheavytail,with0.

1%ofinter-querytimesbeingover25minutes.

Intuitively,longinter-querytimesrepresentoperiodswhentheclient'suserisawayfromthekeyboard(e.

g.

,asleeporatclass).

TheOthersdatasetsshowwiderangingbehaviorsuggestingthattheyarelessamenabletosuccinctdescriptioninanaggregatemodel.

FortheUsersdataset,weareabletomodeltheaggregateinter-querytimedistributionusingtheWeibulldistributionforthebodyandtheParetodistri-butionfortheheavytail.

Wendthatpartitioningthedataataninter-querytimeof22secondsminimizesthemeansquarederrorbetweenthedataandthetwoanalyticaldistributions.

Next,wettheanalyticaldistributions—splitat22seconds—toeachoftheindividualclientinter-querytimedistributions.

Wendthatwhiletheparametersvaryperclient,theempiricaldataiswellrepre-sentedbytheanalyticalmodelsasthemeansquarederrorfor90%ofclientsislessthan0.

0014.

Thus,parametersforamodelofqueryinter-arrivalswillvaryperclient,butthedistributionisinvariant.

Next,wemovefromfocusingonindividuallookupstofocusingontimingrelatedtothe1Mlookupclustersthatencompass12M(80%)ofthequeriesinourdataset(see§4).

Figure4showsourresults.

The"Intra-clustertime"lineshowsthedistributionofthetimebetweensuccessivequerieswithinthesamecluster.

Thistimeisboundedtoε=2.

5secondsbyconstruction,butover90%oftheinter-arrivalsarelessthan1second.

Ontheotherhand,theline"Inter-clusterFig.

5.

Fractionofqueriesissuedforeachhostnameperclient.

Fig.

6.

FractionofclientsissuingqueriesforeachhostnameandSLD.

time"showsthetimebetweenthelastqueryofaclusterandtherstqueryofthenextcluster.

Again,mostclustersareseparatedfromeachotherbymuchmorethanεtime,theminimumseparationbyconstruction.

Theline"Clusterduration"showsthetimebetweentherstandlastqueryineachcluster.

Mostclustersareshort,with99%lessthan18seconds.

Additionally,wendthatmostofclientDNStracoccursinshortclusters:50%ofclusteredqueriesbelongtoclusterswithdurationlessthan4.

6secondsand90%areinclusterswithdurationlessthan20seconds.

FortheOthersdatasets,asmallerpercentageofDNSqueriesoccurinclusters—e.

g.

,60%intheFeb:Residential:Othersdataset.

6QueryTargetsFinally,wetacklethequeriesthemselvesincludingrelationshipsbetweenqueries.

PopularityofNames:Weanalyzethepopularityofhostnamesusingtwomethods—howoftenthenameisqueriedacrossthedatasetandhowmanyclientsqueryforit.

Figure5showsthefractionofqueriesforeachhostname(withthehostnamessortedbydecreasingpopularity)intheFeb:Residential:Usersdataset.

Per§5,weplottheaggregatedistributionandarangethatencompasses90%oftheindividualclientdistributions.

Ofthe499Kuniquehostnameswithinourdataset,256K(51%)arelookeduponlyonce.

Meanwhile,thetop100hostnamesaccountfor28%ofDNSqueries.

Figure6showsthefractionofclientsthatqueryforeachname.

Wendthat77%ofhostnamesarequeriedbyonlyasingleclient.

However,over90%oftheclientslookupthe14mostpopularhostnames.

Additionally,13ofthesehostnamesareGoogleservicesandtheremainingoneiswww.

facebook.

com.

Theplotshowssimilarresultsforsecond-leveldomains(SLDs),where66%oftheSLDsarelookedupbyasingleclient.

Thedistributionsofbothqueriespernameandclientspernamedemonstratepowerlawbehaviorinthetail.

Interestingly,thePearsoncorrelationbetweenthesetwometrics—popularitybyqueriesandpopularitybyclients—isonly0.

54indicatingthatadomainnamewithmanyqueriesisnotnecessarilyqueriedbyalargefractionoftheclientpopulationandviceversa.

Asanexample,update-keepalive.

mcafee.

comisthe19thmostqueriedhostnamebutisonlyqueriedby8.

1%oftheclients.

Atthesametime,55%oftheclientsqueryfors2.

symcb.

com,butintermsoftotalqueriesthishostnameranksasonlythe1215thmostpop-ular.

ThisphenomenonmaybepartiallyexplainedbydierencesinTTL.

Therecordfors2.

symcb.

comhasaonehourTTL—limitingthequeryfrequency.

Meanwhile,updatekeepalive.

mcafee.

comhasa1minuteTTL.

GiventhisshortTTLandthatthenameimpliespollingactivity,thelargenumbersofqueriesfromagivenclientisunsurprising.

Thus,amodelofDNSclientbehaviormustaccountforthepopularityofhostnamesintermsofbothqueriesandclients.

TheheavytailsofthepopularitydistributionsrepresentalargefractionofDNStransactions.

However,wecannotdisregardunpopularnames—eventhosequeriedjustonce—becausetogethertheyareresponsibleforthemajorityofDNSactivitythereforeimpactingtheentireDNSecosystem(e.

g.

,cachebehavior).

Co-occurrenceNameRelationships:Inadditiontounderstandingpopular-ity,wenextassesstherelationshipsbetweennames,asthesehaveimplicationsonhowtomodelclientbehavior.

Thecrucialrelationshipbetweentwonamesthatweseektoquantifyisfrequentqueryingforthepairtogether.

Webeginwiththerequestclusters(§4)andleveragetheintuitionthattherstquerywithinaclustertriggersthesubsequentqueriesintheclusterandisthereforetherootlookup.

Thisfollowsfromthestructureofmodernwebpages,withacontainerpagecallingforadditionalobjectsfromavarietyofservers—e.

g.

,anaveragewebpageusesobjectsfrom16dierenthostnames[10].

Findingco-occurrenceiscomplicatedduetoclientcaching.

Thatis,wecannotexpecttoseetheentiresetofdependentlookupseachtimeweobservesomerootlookup.

Ourmethodologyfordetectingco-occurrenceisasfollows.

First,wedeneclusters(r)asthenumberofclusterswithrastherootacrossourdatasetandpairs(r,d)asthenumberofclusterswithrootrthatincludedependentd.

Second,welimitouranalysistothecasewhenclusters(r)≥10toreducethepotentialforfalsepositiverelationshipsbasedontoofewsamples.

IntheFeb:Residential:Usersdataset,wend7.

1K(9.

9%)oftheclustersmeetthesecriteria.

Withintheseclusterswend7.

5Mdependentqueriesand2.

2Munique(r,d)pairs.

Third,foreachpair(r,d),wecomputetheco-occurrenceasC=pairs(r,d)/clusters(r)—i.

e.

,thefractionoftheclusterswithrootrthatincluded.

Co-occurrenceofmostpairsislowwith2.

0M(93%)pairshavingaCmuchlessthan0.

1.

Wefocusonthe78KpairsthathavehighC—greaterthan0.

2.

Thesepairsinclude98%oftherootsweidentify,i.

e.

,nearlyallrootshaveatleastonedependentwithwhichtheyco-occurfrequently.

Also,thesepairscomprise28%ofthe7.

5Mdependentquerieswestudy.

Wenotethatintuitivelydependentnamescouldbeexpectedtosharelabelswiththeirroots—e.

g.

,www.

facebook.

comandstar.

c10r.

facebook.

com—andthiscouldbeafurtherwaytoassessco-occurrence.

However,wendthatonly27%ofthepairswithinclusterswithco-occurrenceofatleast0.

2sharethesameSLDand11%sharethe3rdlevellabelastheclusterroot.

Thissuggeststhatwhilenotrare,countingonco-occurringnamestobefromthesamezonetobuildclustersisdubious.

Asanextremeexample,GoogleAnalyticsisadependentof1,049uniqueclusterroots,mostofwhicharenotGooglenames.

Fig.

7.

Cosinesimilaritybetweenthequeryvectorsforthesameclient.

Fig.

8.

Cosinesimilaritybetweenthequeryvectorsfordierentclients.

Finally,wecannottestthemajorityoftheclustersandpairsforco-occurrencebecauseoflimitedsamples.

However,wehypothesizethatourresultsapplytoallclusters.

WenotethatthedistributionofthenumberofqueriesperclusterinFigure1issimilartothedistributionofthenumberofdependentsperrootwheretheco-occurrencefractionisgreaterthan0.

2.

Combiningourobservationsthat80%ofqueriesoccurinclusters,28%ofthedependentquerieswithinclustershavehighco-occurrencewiththeroot,andtheaverageclusterhas1rootand10dependents,weestimatethatataminimum800.

2810/11=20%ofDNSqueriesaredrivenbyco-occurrencerelationships.

Weconcludethatco-occurrencerelationshipsarecommon,thoughtherelationshipsdonotalwaysmanifestasrequestsonthewireduetocaching.

TemporalLocality:Wenextexplorehowthesetofnamesaclientquerieschangesovertime.

Asafoundation,weconstructavectorVc,dforeachclientcandeachdaydinourdataset,whichrepresentsthefractionoflookupsforeachnameweobserveinourdataset.

Specically,westartfromanalphabeticallyorderedlistofallhostnameslookedupacrossallclientsinourdataset,N.

WeinitiallyseteachVc,dtoavectorof|N|zeros.

WetheniteratethroughNandsetthecorrespondingpositionineachVc,dasthetotalnumberofqueriesclientcissuesfornameNiondayddividedbythetotalnumberofqueriescissuesondayd.

Thus,anexampleVc,dwouldbeinthecasewheretherearevetotalnamesinthedatasetandondaydtheclientqueriesforthesecondnameonce,thefourthnametwiceandthefthnameonce.

WerepeatthisprocessusingonlytheSLDsfromeachquery,aswell.

Werstinvestigatewhetherclients'queriestendtoremainstableacrossdaysinthedataset.

Forthis,wecomputetheminimumcosinesimilarityofthequeryvectorsforeachclientacrossallpairsofconsecutivedays.

Figure7showsthedistributionofminimumcosinesimilarityperclientintheFeb:Residential:Usersdataset.

Ingeneral,thecosinesimilarityvaluesarehigh—greaterthan0.

5for80%ofclientsforuniquehostnames—indicatingthatclientsqueryforasimilarsetofnamesinsimilarrelativefrequenciesacrossdays.

Giventhisresult,itisunsurprisingthatthegurealsoshowshighsimilarityacrossSLDs.

Fig.

9.

MeanhostnamesandSLDsqueriedbyeachclientperday.

Fig.

10.

Meanandmedianstackdistanceforeachclient.

Nextweassesswhetherdierentclientsqueryforsimilarsetsofnames.

Wecomputethecosinesimilarityacrossallpairsofclientsandforalldaysofourdataset.

Figure8showsthedistributionofthemaximumsimilarityperclientpairfromanyday.

Whenconsideringhostnames,wendlowersimilarityvaluesthanwhenfocusingonasingleclient—withonly3%showingsimilarityofatleast0.

5—showingthateachclientqueriesforafairlydistinctsetofhostnames.

ThesimilaritybetweenclientsisalsolowforsetsofSLDs,with55%ofthepairsshowingamaximumsimilaritylessthan0.

5.

Thus,clientsqueryfordierentspecichostnamesanddistinctsetsofSLDs.

TheseresultsshowthataclientDNSmodelmustensurethat(i)eachclienttendstostaysimilaracrosstimeandalsothat(ii)clientsmustbedistinctfromoneanother.

Analaspectweexploreishowquicklyaclientrepeatsaquery.

AsweshowinFigure2,50%oftheclientssendlessthan2Kqueriesperdayonaverage.

Figure9showsthedistributionoftheaveragenumberofuniquehostnamesthatclientsqueryperday.

Thenumberofnamesislessthantheoverallnumberoflookups,indicatingthepresenceofrepeatqueries.

Forinstance,atthemedian,aclientqueriesfor400uniquehostnamesand150SLDseachday.

Toassessthetemporallocalityofre-queries,wecomputethestackdistance[12]foreachquery—thenumberofuniquequeriessincethelastqueryforthegivenname.

Figure10showsthedistributionsofthemeanandmedianstackdistanceperclient.

Wendthestackdistancetoberelativelyshortinmostcases—withover85%ofthemediansbeinglessthan100.

However,thelongermeansshowthatthere-userateisnotalwaysshort.

Ourresultsshowthatvariationinrequeryingbehaviorexistsamongclients,withsomeclientsrevisitingnamesfrequentlyandothersqueryingalargersetofnameswithlessfrequency.

7RelatedWorkModelsofvariousprotocolshavebeenconstructedforunderstanding,simulat-ingandpredictingtrac(e.

g.

,[13]foravarietyoftraditionalprotocolsand[2]asanexampleofHTTPmodeling).

Additionally,thereispreviousworkoncharacterizingDNStrac(e.

g.

,[11,6]),whichfocusesontheaggregatetracofapopulationofclients,incontrasttoourfocusonindividualclients.

Finally,wenote—aswediscussin§1—thatseveralrecentstudiesinvolvingDNSmakeassumptionsaboutthebehaviorofindividualclientsorneedtoanalyzedataforspecicinformationbeforeproceeding.

Forinstance,theauthorsof[5]modelDNShierarchicalcacheperformanceusingananalyticalarrivalprocess,whilein[14],theauthorsusesimulationtoexplorechangestotheresolutionpath.

BothstudieswouldbenetfromagreaterunderstandingofDNSclientbehavior.

8ConclusionThisworkisaninitialsteptowardsrichlyunderstandingindividualDNSclientbehavior.

Wecharacterizeclientbehaviorinwaysthatwillultimatelyinformananalyticalmodel.

WendthatdierenttypesofclientsinteractwiththeDNSindistinctways.

Further,DNSqueriesoftenoccurinshortclustersofrelatednames.

Asasteptowardsananalyticalmodel,weshowthattheclientqueryarrivalprocessiswellmodeledbyacombinationoftheWeibullandParetodistributions.

Inaddition,wendthatclientshavea"workingset"ofnamesthatisbothfairlystableovertimeandfairlydistinctfromotherclients.

Fi-nally,ourhigh-levelresultsholdacrossbothtimeandqualitativelydierentuserpopulations—studentresidentialvs.

Universityoce.

Thisisaninitialindicationthatthebroadpropertiesweilluminateholdthepromisetobeinvariants.

References1.

OpenDNS.

http://www.

opendns.

com/.

2.

P.

BarfordandM.

Crovella.

GeneratingRepresentativeWebWorkloadsforNet-workandServerPerformanceEvaluation.

InACMSIGMETRICS,1998.

3.

T.

Callahan,M.

Allman,andM.

Rabinovich.

OnModernDNSBehaviorandProperties.

ACMSIGCOMMComputerCommunicationReview,July2013.

4.

M.

Ester,H.

-P.

Kriegel,J.

Sander,andX.

Xu.

ADensity-BasedAlgorithmforDiscoveringClustersinLargeSpatialDatabaseswithNoise.

InAAAIInternationalConferenceonKnowledgeDiscoveryandDataMining,1996.

5.

N.

C.

FofackandS.

Alouf.

ModelingModernDNSCaches.

InACMInternationalConferenceonPerformanceEvaluationMethodologiesandTools,2013.

6.

H.

Gao,V.

Yegneswaran,Y.

Chen,etal.

AnEmpiricalRe-examinationofGlobalDNSBehavior.

InACMSIGCOMM,2013.

7.

P.

Gauthier,J.

Cohen,andM.

Dunsmuir.

TheWebProxyAuto-DiscoveryPro-tocol.

IETFInternetDraft.

https://tools.

ietf.

org/html/draft-ietf-wrec-wpad-01(workinprogress),1999.

8.

WebsitesUsingGoogleAnalytics.

http://trends.

builtwith.

com/analytics/Google-Analytics.

9.

GoogleSafeBrowsing.

https://developers.

google.

com/safe-browsing.

10.

HTTPArchive.

http://httparchive.

org.

11.

J.

Jung,A.

W.

Berger,andH.

Balakrishnan.

ModelingTTL-BasedInternetCaches.

InIEEEInternationalConferenceonComputerCommunications,2003.

12.

R.

L.

Mattson,J.

Gecsei,D.

R.

Slutz,andI.

L.

Traiger.

EvaluationTechniquesforStorageHierarchies.

IBMSystemsJournal,1970.

13.

V.

Paxson.

EmpiricallyDerivedAnalyticModelsofWide-AreaTCPConnections.

IEEE/ACMTransactionsonNetworking,1994.

14.

K.

Schomp,M.

Allman,andM.

Rabinovich.

DNSResolversConsideredHarmful.

InACMWorkshoponHotTopicsinNetworks,2014.

TheDomainNameSystem(DNS)isacriticalcomponentoftheInternetinfrastructureasitmapshuman-readablehostnamesintotheIPaddressesthenetworkusestoroutetrac.

Yet,theDNSbehaviorofindividualclientsisnotwellunderstood.

Inthispaper,wepresentacharacterizationofDNSclientswithaneyetowardsdevelopingananalyticalmodelofclientinteractionwiththelargerDNSecosystem.

WhilethisisinitialworkandwedonotarriveataDNSworkloadmodel,wehighlightavarietyofbehaviorsandcharacteristicsthatenhanceourmentalmodelsofhowDNSoperatesandmoveustowardsananalyticalmodelofclient-sideDNSoperation.

1IntroductionThemodernInternetreliesontheDomainNameSystem(DNS)fortwomainfunctions.

First,theDNSallowspeopletoleveragehuman-friendlyhostnames(e.

g.

,"www.

cnn.

com")insteadofobtuseIPaddressestoidentifyahost.

Second,hostnamesprovidealayerofabstractionsuchthattheIPaddressassignedtoahostnamecanvaryovertime.

Inparticular,ContentDistributionNetworks(CDNs)employthislatebindingtodirectuserstothebestcontentreplica.

PreviousworkshowsthatDNSlookupsprecedeover60%ofTCPconnections[14].

Asaresult,individualclientsissuelargenumbersofDNSqueries.

Yet,ourunderstandingofDNSquerystreamsislargelybasedonaggregatepopula-tionsofclients—e.

g.

,atanorganizational[6]orresidentiallevel[3]—leavingourknowledgeofindividualclientbehaviorlimited.

ThispaperrepresentsaninitialsteptowardsunderstandingindividualclientDNSbehavior.

WemonitorDNStransactionsbetweenapopulationofthousandsofclientsandtheirlocalresolversuchthatweareabletodirectlytielookupstoindividualclients.

OurultimategoalisananalyticalmodelofDNSclientbehaviorthatcanbeusedforeverythingfromworkloadgenerationtoresourceprovisioningtoanomalydetection.

InthispaperweprovideacharacterizationofDNSbehavioralongthedimensionsourmodelwillultimatelycoverandalsoanecdotallyshowpromisingmodelingapproaches.

Note,oneviewholdsthatDNSisa"sideservice"andshouldnotbedirectlymodeled,butrathercanbewellunderstoodbyderivingtheDNSworkloadfromapplicationssuchaswebbrowsingandemailtransmission.

However,derivingaDNSworkloadfromapplicationbehaviorisatbestdicultbecause(i)clientThisworkwasfundedinpartbyNSFgrantCNS-1213157.

cachingpoliciesimpactwhatDNSqueriesareactuallysentinresponsetoanapplicationevent,(ii)someapplicationsselectivelyusepre-fetchingtolookupnamesbeforetheyareneededand(iii)suchaderivationwouldentailunder-standingmanyapplicationstopulltogetherareasonableDNSworkload.

There-fore,wetaketheapproachthatfocusingontheDNStracitselfisthemosttractablewaytounderstand—andeventuallymodel—namelookups.

Tomotivatetheneedforamodel,weprovideanexemplarfromourpreviouswork.

In[14],weproposethatclientsshoulddirectlyresolvehostnamesinsteadofusingarecursiveresolver.

Ideally,anevaluationofthisendsystem-basedmech-anismwouldbeconductedinthecontextofendsystemsthemselves.

However,thebestdatawecouldobtainwasatthelevelofindividualhouseholds—whichweknowtoincludemultiplehostsbehindaNAT.

Therefore,theresultsofourtrace-drivensimulationsareatbestanapproximationoftheimpactofthemech-anismwewereinvestigating.

OurresultswouldhavebeenmoreprecisehadwebeenabletoleverageamodelofindividualclientDNSbehavior.

Broadly,theremainderofthispaperfollowsthecontoursofwhatamodelwouldcapture.

Werstfocusonunderstandingthenatureoftheclientsthem-selvesin§3,ndingthatwhilemostaretraditionaluser-facingdevices,thereareothersthatinteractwiththeDNSindistinctways.

Nextweobservein§4thatDNSqueriesoftenoccurclosely-spacedintime—e.

g.

,drivenbyloadingobjectsforasinglewebpagefromdisparateservers—andthereforewedevelopamethodtogathertogetherqueriesintoclusters.

Wethenassessthenumberandspacingofqueriesin§5andnallytacklethepatternsinwhathostnamesindividualclientslookupin§6.

Wendthatclientshavefairlydistinct"workingsets"ofnames,andalsothathostnamepopularityhaspowerlawproperties.

2DatasetOurdatasetcomesfromtwopackettapsatCaseWesternReserveUniversity(CWRU)thatmonitorthelinksconnectingthetwodatacentersthathouseallveoftheUniversity'sDNSresolvers—i.

e.

,betweenclientdevicesandtheirre-cursiveDNSresolvers.

WecollectfullpayloadpackettracesofallUDPtracinvolvingport53(thedefaultDNSport).

ThecampuswirelessnetworksituatesclientdevicesbehindNATsandthereforewecannotisolateDNStractoin-dividualclients.

Hence,wedonotconsiderthistracinourstudy(although,futureworkremainstobetterunderstandDNSusageonmobiledevices).

TheUniversityAcceptableUsePolicyprohibitstheuseofNATonitswirednetworkswhileoeringwirelessaccessthroughoutthecampus,andthereforewebelievethetracwecapturefromthewirednetworkdoesrepresentindividualclients.

OurdatasetincludesallDNStracfromtwoseparateweeksandispartitionedbyclientlocation—intheresidentialoroceportionsofthenetwork.

DetailsofthedatasetsaregiveninTable1includingthenumberofqueries,thenumberofclientsthatissuethosequeries,andthenumberofhostnamesqueried.

Validation:DuringtheFebruarydatacollection,wecollectquerylogsfromthevecampusDNSresolverstovalidateourdatasets1.

Comparingthepacket1Weprefertracesoverlogsduetothebettertimestampresolution(msecvs.

sec).

DatasetDatesQueriesClientsHostnamesFeb:ResidentialFeb.

26-Mar.

432.

5M1359(IPs)652KFeb:Residential(lter)Feb.

26-27,Mar.

2-416.

4M1262(MACs)505KFeb:Residential:Users15.

3M1033499KFeb:Residential:Others1.

11M2297.

94KFeb:OceFeb.

26-Mar.

4232M8770(IPs)1.

98MFeb:Oce(lter)Feb.

26-27,Mar.

2-4143M8690(MACs)1.

87MFeb:Oce:Users118M59861.

52MFeb:Oce:Others25.

0M2704158KJun:ResidentialJun.

23-Jun.

2911.

7M345(IPs)140KJun:Residential(lter)Jun.

23-26,296.

22M334(MACs)120KJun:Residential:Users5.

81M204116KJun:Residential:Others408K1304.

13KJun:OceJun.

23-Jun.

29245M8335(IPs)1.

61MJun:Oce(lter)Jun.

23-26,29133M8286(MACs)1.

52MJun:Oce:Users108M54951.

42MJun:Oce:Others25.

0M279163.

1KTable1.

Detailsofthedatasetsusedinthisstudy.

tracesandlogswenda0.

6%and1.

8%lossratesintheFeb:ResidentialandFeb:Ocedatasets,respectively.

Webelievetheselossesareanartifactofourmeasurementapparatusgiventhatthelossrateiscorrelatedwithtracvolume.

TrackingClients:Weaimtotrackindividualclientsinthefaceofdynamicaddressassignment.

SimultaneouslywiththeDNSpackettrace,wegatherlogsfromtheUniversity'sthreeDHCPservers.

Therefore,wecantrackDNSactivitybasedonMACaddresses.

Note,wecouldnotmap1.

3%ofthequeriesacrossourdatasetstoaMACaddressbecausethesourceIPaddressinthequeryneverappearsintheDHCPlogs.

TheselikelyrepresentstaticIPaddressallocations.

Further,withoutanyDHCPassignmentswearecondentthattheseIPsrepre-sentasinglehost.

FilteringDatasets:Wendtwoanomaliesthatskewthedatainwaysthatarenotindicativeofuserbehavior.

First,wendroughly25%ofthequeriesrequesttheTXTrecordfordebug.

opendns.

com.

(Thenextmostpopularrecordrepre-sentslessthan1%ofthelookups!

)Wendthisqueryisnotinresponsetousers'actions,butisautomaticallyissuedtodeterminewhethertheclientisusingtheOpenDNSresolver(indicatedintheanswer)[1].

Weobserve298clientsqueryingthisrecord,whichweassumeuseOpenDNSonothernetworksorusedOpenDNSinthepast.

Weremovethesequeriesfromfurtheranalysis.

Thesecondanomalyinvolves18clientswhoseprominentbehavioristoqueryfordebug.

opendns.

comandotherdomainsrepeatedlywithoutevidenceofaccomplishingmuchwork.

Thecampusinformationtechnologydepartmentveriedthattheseclientsserveanoperationalpurposeandarenotuser-facingdevices.

Therefore,weremovethe18clientsastheyarelikelyuniquetothisnetworkanddonotrepresentusers.

Wedonotattempttofurtherltermisbehavinghosts—e.

g.

,infectedormisconguredhosts—asweconsiderthempartoftheDNSworkload(e.

g.

,sincearesolverwouldberequiredtocopewiththeirrequests).

Timeframe:TomoredirectlycompareresidentialandocesettingsweexcludeSaturdayandSundayfromourdatasets.

Table1showsthemagnitudeofourltering.

Wendcommonalityacrossthepartitionsofthedata,sowefocusontheFeb:Residential:Usersdatasetforconcisenessanddiscusshowotherdatasetsdierasappropriate.

MarkerClients%All1262100%Googleanalytics98378%Searchengine101080%Google100680%Anyother60248%Gmail88170%LDAPLogin84066%Any103382%Table2.

Feb:Residentialclientsthattmarkersforgeneralpurposedevices.

3IdentifyingTypesofClientsSinceourfocusisoncharacterizinggeneralpurposeuser-facingdevices,weaimtoseparatethemfromothertypesofendsystems.

Weexpectgeneral-purposesys-temsareinvolvedintasks,suchas(i)webbrowsing,(ii)accessingsearchengines,(iii)usingemail,and(iv)conductinginstitutional-specictasks2.

Therefore,wedevelopthefollowingmarkerstoidentifygeneral-purposehosts:Browsing:AlargenumberofwebsitesembedGoogleAnalytics[8]intheirpages,thusthereisahighlikelihoodthatregularuserswillqueryforGoogleAnalyticshostnamesonoccasion.

Searching:WedetectwebsearchactivityviaDNSqueriesforthelargestsearchengines:Google,Yahoo,Bing,AOL,Ask,DuckDuckGo,Altavista,Baidu,Lycos,Excite,Naver,andYandex.

Email:CWRUusesGoogletomanagecampusemailandthereforeweusequeriesfor"mail.

google.

com"toindicateemailuse.

Institutional-SpecicTasks:CWRUusesasinglesign-onsystemforauthen-ticatingusersbeforetheyperformavarietyoftasksandthereforeweusequeriesforthecorrespondinghostnameasindicativeofuserbehavior.

Table2showsthebreakdownoftheclientsintheFeb:Residentialdataset.

Ofthe1,262clientsweidentify1,033asuser-facingbasedonatleastoneoftheabovemarkers.

Intuitivelyweexpectthatmultiplemarkerslikelyapplytomostgeneralpurposesystemsandinfactwendatleasttwomarkersapplyto991oftheclientsinourdataset.

Resultsforourotherdatasetsaresimilar.

Wenextturntothe229clients(≈18%)thatdonotmatchanyofourmark-ersforuser-facingclients.

TobetterunderstandtheseclientsweaggregatethembasedonthevendorportionoftheirMACaddresses.

First,wendasetofven-dorsandquerystreamsthatindicatespecial-purposedevices:(i)48Microsoftdevicesthatqueryfornameswithinthexboxlive.

comdomain,whichweconcludeareXboxgamingconsoles,(ii)33Sonydevicesthatqueryfornameswithintheplaystation.

netdomain,whichweconcludeareSonyPlaystationgamingcon-soles,(iii)16Appledevicesthathaveanaverageof11Kqueries—representing96%oftheirlookups—fortheapple.

comdomain,eventhoughtheaverageacrossalldevicesthatlookupanapple.

comnameis262queries,whichweconcludeareAppleTVdevicesand(iv)7Linksysdevicesthatissuequeriesfores-uds.

usatech.

com,whichweconcludearetransactionsystemsattachedtothelaundrymachinesintheresidencehalls(!

).

2Inourcase,thisiscampus-lifetasks,e.

g.

,checkingthecoursematerialsportal.

Inadditiontothese,wenddevicesthatwecannotpinpointexplicitly,butdonotinfactseemtobegeneral-purposeclientsystems.

Wend41DelldevicesthatdierfromthelargerpopulationofhostsinthattheyqueryformorePTRrecordsthanArecords.

Apotentialexplanationisthatthesedevicesareserversobtaininghostnamesforclientsthatconnecttothem(e.

g.

,aspartofsshd'svericationstepsortologclientconnects).

Wealsoidentify12KyoceradevicesthatissuequeriesforonlythecampusNTPandSMTPservers.

Weconcludethatthesearecopymachinesthatalsooeremailingofscanneddocuments.

FortheIPaddressesthatdonotappearintheDHCPlogs(i.

e.

,addressesstaticallyconguredonthehosts),wecannotobtainavendorID.

However,wenotethat97%ofthequeriesand96%oftheuniquedomainnamesfromthesemachinesinvolveCWRUdomainsandthereforeweconcludethattheyservesomeadministrativefunctionandarenotgeneralpurposeclients.

Theremaining61devicesaredistributedamong42hardwarevendors.

Intheremainderofthepaperwewillconsiderthegeneralpurposeclients(Users)andthespecialpurposeclients(Others)separately,aswedetailinTable1.

Wendthatourhigh-levelobservationsholdacrossalloftheUsersdatasets,andthuspresentresultsfortheFeb:Residential:Usersdatasetonly.

4QueryClustersApplicationsoftencallformultipleDNSqueriesinrapidsuccession—e.

g.

,aspartofloadingallobjectsonawebpage,orprefetchingnamesforlinksusersmayclick.

Inthissection,wequantifythisbehaviorusingtheDBSCANalgorithm[4]toconstructclustersofDNSqueriesthatlikelyshareanapplicationevent.

TheDBSCANalgorithmusestwoparameterstoformclusters:aminimumclustersizeMandadistanceεthatcontrolstheadditionofsamplestoacluster.

Weusetheabsolutedierenceinthequerytimestampsasthedistancemetric.

Ourrsttaskistochoosesuitableparameters.

Ourstrategyistostartwitharangeofparametersanddeterminewhetherthereisapointofconvergencewheretheresultsofclusteringdonotchangegreatlywiththeparameters.

Basedonthestrategyin[4],westartwithanMrangeof3–6andanεrangeof0.

5–5seconds—notethatM=2simpliestothresholdbasedclustering,butdoesnotproduceapointofconvergence.

Wendthat96%oftheclustersweidentifywithM=6areexactlyfoundwhenM=3andhenceatM=3wehaveconvergedonareasonablystableanswerwhichweuseinthesubsequentanalysis.

Additionally,wendthatforε∈[2.

5,5],thetotalnumberofclusters,thedistributionofclustersizes,andtheassignmentofqueriestoclustersremainsimilarirrespectiveofεvalueandthereforeuseε=2.

5secondsinouranalysis.

WedenetherstDNSqueryperclusterastherootandallsubsequentqueriesintheclusterasdependents.

IntheFeb:Residential:Usersdataset,wend1Mclustersthatencompass80%oftheroughly15Mqueriesinthedataset.

Tovalidatetheclusteringalgorithmwerstinspectthe67Kuniquehost-namesthealgorithmlabelsasnoise.

Wendavarietyofhostnameswiththemostfrequentbeing:WPAD[7]queriesfordiscoveringproxies,GoogleMailandGoogleDocs,softwareupdatepolling(e.

g.

,McAfeeandSymantec),heart-beatsignalsforgamingapplications(e.

g.

,Origin,Steam,Blizzard,Riot),videoFig.

1.

Numberofqueries,hostnames,andSLDspercluster.

Fig.

2.

Queriesissuedbyeachclientperday.

streaming(e.

g.

,Netix,YouTube,Twitch),andtheNetworkTimeProtocol(NTP).

AllofthesenamescanintuitivelycomefromapplicationsthatrequireonlysporadicDNSqueries,astheyareeithermakingquickcheckseveryonceinawhile,orareusinglong-livedsessionsthatleverageDNSonlywhenstarting.

Tovalidatetheclustersthemselves,weobservethattherearefrequentlyoc-curringroots.

Indeed,the1Mclustershaveonly72Kuniqueroots,withthe100mostfrequentlyoccurringrootsaccountingfor395K(40%)oftheclusters.

Fur-ther,the100mostpopularrootsincludepopularwebsites(e.

g.

,www.

facebook.

com,www.

google.

com).

Thesearethetypeofnameswewouldexpecttoberootsinthecontextofwebbrowsing.

Anothercommonrootissafebrowsing.

google.

com[9],ablacklistdirectoryusedbysomewebbrowserstodetermineifagivenwebsiteissafetoretrieve.

Thisisadistinctlydierenttypeofrootthanapopularwebsitebecausetherootisnotdirectlyrelatedtothedependentsbythepagecontent,butratherviaaprocessrunningontheclients.

ThisinsomesensemeansSafeBrowsing-basedclustershavetworoots.

WhileuseofSafeBrowsingisfairlycommoninourdataset,wedonotndadditionalprevalentcasesofthis"tworoots"phenomenon.

Fromamodelingstandpointwehavenotyetdeterminedwhether"tworoots"clusterswouldneedspecialtreatment.

Figure1showsthedistributionofqueriespercluster.

Whilethemajor-ityofclustersaresmall,therearerelativelyfewlargeclusters.

Wendthat90%ofclusterscontainatmost26queriesforatmost22hostnames.

Addi-tionally,wend90%oftheclustersencompassatmost10SLDs.

Thelargestclusterspans95secondsandconsistsof9,366queriesfornamesthatmatchtothe3rdlevellabel.

Thesecondlargestclusterconsistsof6,211queriesformyapps.

developer.

ubuntu.

com—whichislikelyaUbuntubug.

5QueryTimingNextwetacklethequestionofwhenandhowmanyqueriesclientsissue.

Webeginwiththedistributionoftheaveragenumberofqueriesthatclientsissueperday,Fig.

3.

Timebetweenqueriesfromthesameclientinaggregateandperclient.

Fig.

4.

Durationofclusters,inter-clusterquerytimeandintra-clusterquerytime.

asgiveninFigure2.

WendthatclientsinUsersissue2Klookupsperdayatthemedianand90%ofclientsinUsersissuelessthan6.

7Kqueriesperday.

TheOthersdatasetsshowgreatervariabilitywhererelativelyfewclientsgeneratethelion'sshareofqueries—i.

e.

,thetop5%ofclientsproduceroughlyasmanytotalDNSqueriesperdayasthebottom95%intheFeb:Residential:Othersdataset.

Arelatedmetricisthetimebetweensubsequentqueriesfromthesameclient,orinter-querytimes.

Figure3showsthedistributionoftheinter-querytimes.

The"Aggregate"lineshowsthedistributionacrossallclients.

Thearea"90%"showstherangewithinwhich90%oftheindividualclientinter-querytimedistributionsfall.

Themajorityofinter-querytimesareshort,with50%oflookupsoccurringwithin34millisecondsofthepreviousquery.

However,wealsondaheavytail,with0.

1%ofinter-querytimesbeingover25minutes.

Intuitively,longinter-querytimesrepresentoperiodswhentheclient'suserisawayfromthekeyboard(e.

g.

,asleeporatclass).

TheOthersdatasetsshowwiderangingbehaviorsuggestingthattheyarelessamenabletosuccinctdescriptioninanaggregatemodel.

FortheUsersdataset,weareabletomodeltheaggregateinter-querytimedistributionusingtheWeibulldistributionforthebodyandtheParetodistri-butionfortheheavytail.

Wendthatpartitioningthedataataninter-querytimeof22secondsminimizesthemeansquarederrorbetweenthedataandthetwoanalyticaldistributions.

Next,wettheanalyticaldistributions—splitat22seconds—toeachoftheindividualclientinter-querytimedistributions.

Wendthatwhiletheparametersvaryperclient,theempiricaldataiswellrepre-sentedbytheanalyticalmodelsasthemeansquarederrorfor90%ofclientsislessthan0.

0014.

Thus,parametersforamodelofqueryinter-arrivalswillvaryperclient,butthedistributionisinvariant.

Next,wemovefromfocusingonindividuallookupstofocusingontimingrelatedtothe1Mlookupclustersthatencompass12M(80%)ofthequeriesinourdataset(see§4).

Figure4showsourresults.

The"Intra-clustertime"lineshowsthedistributionofthetimebetweensuccessivequerieswithinthesamecluster.

Thistimeisboundedtoε=2.

5secondsbyconstruction,butover90%oftheinter-arrivalsarelessthan1second.

Ontheotherhand,theline"Inter-clusterFig.

5.

Fractionofqueriesissuedforeachhostnameperclient.

Fig.

6.

FractionofclientsissuingqueriesforeachhostnameandSLD.

time"showsthetimebetweenthelastqueryofaclusterandtherstqueryofthenextcluster.

Again,mostclustersareseparatedfromeachotherbymuchmorethanεtime,theminimumseparationbyconstruction.

Theline"Clusterduration"showsthetimebetweentherstandlastqueryineachcluster.

Mostclustersareshort,with99%lessthan18seconds.

Additionally,wendthatmostofclientDNStracoccursinshortclusters:50%ofclusteredqueriesbelongtoclusterswithdurationlessthan4.

6secondsand90%areinclusterswithdurationlessthan20seconds.

FortheOthersdatasets,asmallerpercentageofDNSqueriesoccurinclusters—e.

g.

,60%intheFeb:Residential:Othersdataset.

6QueryTargetsFinally,wetacklethequeriesthemselvesincludingrelationshipsbetweenqueries.

PopularityofNames:Weanalyzethepopularityofhostnamesusingtwomethods—howoftenthenameisqueriedacrossthedatasetandhowmanyclientsqueryforit.

Figure5showsthefractionofqueriesforeachhostname(withthehostnamessortedbydecreasingpopularity)intheFeb:Residential:Usersdataset.

Per§5,weplottheaggregatedistributionandarangethatencompasses90%oftheindividualclientdistributions.

Ofthe499Kuniquehostnameswithinourdataset,256K(51%)arelookeduponlyonce.

Meanwhile,thetop100hostnamesaccountfor28%ofDNSqueries.

Figure6showsthefractionofclientsthatqueryforeachname.

Wendthat77%ofhostnamesarequeriedbyonlyasingleclient.

However,over90%oftheclientslookupthe14mostpopularhostnames.

Additionally,13ofthesehostnamesareGoogleservicesandtheremainingoneiswww.

facebook.

com.

Theplotshowssimilarresultsforsecond-leveldomains(SLDs),where66%oftheSLDsarelookedupbyasingleclient.

Thedistributionsofbothqueriespernameandclientspernamedemonstratepowerlawbehaviorinthetail.

Interestingly,thePearsoncorrelationbetweenthesetwometrics—popularitybyqueriesandpopularitybyclients—isonly0.

54indicatingthatadomainnamewithmanyqueriesisnotnecessarilyqueriedbyalargefractionoftheclientpopulationandviceversa.

Asanexample,update-keepalive.

mcafee.

comisthe19thmostqueriedhostnamebutisonlyqueriedby8.

1%oftheclients.

Atthesametime,55%oftheclientsqueryfors2.

symcb.

com,butintermsoftotalqueriesthishostnameranksasonlythe1215thmostpop-ular.

ThisphenomenonmaybepartiallyexplainedbydierencesinTTL.

Therecordfors2.

symcb.

comhasaonehourTTL—limitingthequeryfrequency.

Meanwhile,updatekeepalive.

mcafee.

comhasa1minuteTTL.

GiventhisshortTTLandthatthenameimpliespollingactivity,thelargenumbersofqueriesfromagivenclientisunsurprising.

Thus,amodelofDNSclientbehaviormustaccountforthepopularityofhostnamesintermsofbothqueriesandclients.

TheheavytailsofthepopularitydistributionsrepresentalargefractionofDNStransactions.

However,wecannotdisregardunpopularnames—eventhosequeriedjustonce—becausetogethertheyareresponsibleforthemajorityofDNSactivitythereforeimpactingtheentireDNSecosystem(e.

g.

,cachebehavior).

Co-occurrenceNameRelationships:Inadditiontounderstandingpopular-ity,wenextassesstherelationshipsbetweennames,asthesehaveimplicationsonhowtomodelclientbehavior.

Thecrucialrelationshipbetweentwonamesthatweseektoquantifyisfrequentqueryingforthepairtogether.

Webeginwiththerequestclusters(§4)andleveragetheintuitionthattherstquerywithinaclustertriggersthesubsequentqueriesintheclusterandisthereforetherootlookup.

Thisfollowsfromthestructureofmodernwebpages,withacontainerpagecallingforadditionalobjectsfromavarietyofservers—e.

g.

,anaveragewebpageusesobjectsfrom16dierenthostnames[10].

Findingco-occurrenceiscomplicatedduetoclientcaching.

Thatis,wecannotexpecttoseetheentiresetofdependentlookupseachtimeweobservesomerootlookup.

Ourmethodologyfordetectingco-occurrenceisasfollows.

First,wedeneclusters(r)asthenumberofclusterswithrastherootacrossourdatasetandpairs(r,d)asthenumberofclusterswithrootrthatincludedependentd.

Second,welimitouranalysistothecasewhenclusters(r)≥10toreducethepotentialforfalsepositiverelationshipsbasedontoofewsamples.

IntheFeb:Residential:Usersdataset,wend7.

1K(9.

9%)oftheclustersmeetthesecriteria.

Withintheseclusterswend7.

5Mdependentqueriesand2.

2Munique(r,d)pairs.

Third,foreachpair(r,d),wecomputetheco-occurrenceasC=pairs(r,d)/clusters(r)—i.

e.

,thefractionoftheclusterswithrootrthatincluded.

Co-occurrenceofmostpairsislowwith2.

0M(93%)pairshavingaCmuchlessthan0.

1.

Wefocusonthe78KpairsthathavehighC—greaterthan0.

2.

Thesepairsinclude98%oftherootsweidentify,i.

e.

,nearlyallrootshaveatleastonedependentwithwhichtheyco-occurfrequently.

Also,thesepairscomprise28%ofthe7.

5Mdependentquerieswestudy.

Wenotethatintuitivelydependentnamescouldbeexpectedtosharelabelswiththeirroots—e.

g.

,www.

facebook.

comandstar.

c10r.

facebook.

com—andthiscouldbeafurtherwaytoassessco-occurrence.

However,wendthatonly27%ofthepairswithinclusterswithco-occurrenceofatleast0.

2sharethesameSLDand11%sharethe3rdlevellabelastheclusterroot.

Thissuggeststhatwhilenotrare,countingonco-occurringnamestobefromthesamezonetobuildclustersisdubious.

Asanextremeexample,GoogleAnalyticsisadependentof1,049uniqueclusterroots,mostofwhicharenotGooglenames.

Fig.

7.

Cosinesimilaritybetweenthequeryvectorsforthesameclient.

Fig.

8.

Cosinesimilaritybetweenthequeryvectorsfordierentclients.

Finally,wecannottestthemajorityoftheclustersandpairsforco-occurrencebecauseoflimitedsamples.

However,wehypothesizethatourresultsapplytoallclusters.

WenotethatthedistributionofthenumberofqueriesperclusterinFigure1issimilartothedistributionofthenumberofdependentsperrootwheretheco-occurrencefractionisgreaterthan0.

2.

Combiningourobservationsthat80%ofqueriesoccurinclusters,28%ofthedependentquerieswithinclustershavehighco-occurrencewiththeroot,andtheaverageclusterhas1rootand10dependents,weestimatethatataminimum800.

2810/11=20%ofDNSqueriesaredrivenbyco-occurrencerelationships.

Weconcludethatco-occurrencerelationshipsarecommon,thoughtherelationshipsdonotalwaysmanifestasrequestsonthewireduetocaching.

TemporalLocality:Wenextexplorehowthesetofnamesaclientquerieschangesovertime.

Asafoundation,weconstructavectorVc,dforeachclientcandeachdaydinourdataset,whichrepresentsthefractionoflookupsforeachnameweobserveinourdataset.

Specically,westartfromanalphabeticallyorderedlistofallhostnameslookedupacrossallclientsinourdataset,N.

WeinitiallyseteachVc,dtoavectorof|N|zeros.

WetheniteratethroughNandsetthecorrespondingpositionineachVc,dasthetotalnumberofqueriesclientcissuesfornameNiondayddividedbythetotalnumberofqueriescissuesondayd.

Thus,anexampleVc,dwouldbeinthecasewheretherearevetotalnamesinthedatasetandondaydtheclientqueriesforthesecondnameonce,thefourthnametwiceandthefthnameonce.

WerepeatthisprocessusingonlytheSLDsfromeachquery,aswell.

Werstinvestigatewhetherclients'queriestendtoremainstableacrossdaysinthedataset.

Forthis,wecomputetheminimumcosinesimilarityofthequeryvectorsforeachclientacrossallpairsofconsecutivedays.

Figure7showsthedistributionofminimumcosinesimilarityperclientintheFeb:Residential:Usersdataset.

Ingeneral,thecosinesimilarityvaluesarehigh—greaterthan0.

5for80%ofclientsforuniquehostnames—indicatingthatclientsqueryforasimilarsetofnamesinsimilarrelativefrequenciesacrossdays.

Giventhisresult,itisunsurprisingthatthegurealsoshowshighsimilarityacrossSLDs.

Fig.

9.

MeanhostnamesandSLDsqueriedbyeachclientperday.

Fig.

10.

Meanandmedianstackdistanceforeachclient.

Nextweassesswhetherdierentclientsqueryforsimilarsetsofnames.

Wecomputethecosinesimilarityacrossallpairsofclientsandforalldaysofourdataset.

Figure8showsthedistributionofthemaximumsimilarityperclientpairfromanyday.

Whenconsideringhostnames,wendlowersimilarityvaluesthanwhenfocusingonasingleclient—withonly3%showingsimilarityofatleast0.

5—showingthateachclientqueriesforafairlydistinctsetofhostnames.

ThesimilaritybetweenclientsisalsolowforsetsofSLDs,with55%ofthepairsshowingamaximumsimilaritylessthan0.

5.

Thus,clientsqueryfordierentspecichostnamesanddistinctsetsofSLDs.

TheseresultsshowthataclientDNSmodelmustensurethat(i)eachclienttendstostaysimilaracrosstimeandalsothat(ii)clientsmustbedistinctfromoneanother.

Analaspectweexploreishowquicklyaclientrepeatsaquery.

AsweshowinFigure2,50%oftheclientssendlessthan2Kqueriesperdayonaverage.

Figure9showsthedistributionoftheaveragenumberofuniquehostnamesthatclientsqueryperday.

Thenumberofnamesislessthantheoverallnumberoflookups,indicatingthepresenceofrepeatqueries.

Forinstance,atthemedian,aclientqueriesfor400uniquehostnamesand150SLDseachday.

Toassessthetemporallocalityofre-queries,wecomputethestackdistance[12]foreachquery—thenumberofuniquequeriessincethelastqueryforthegivenname.

Figure10showsthedistributionsofthemeanandmedianstackdistanceperclient.

Wendthestackdistancetoberelativelyshortinmostcases—withover85%ofthemediansbeinglessthan100.

However,thelongermeansshowthatthere-userateisnotalwaysshort.

Ourresultsshowthatvariationinrequeryingbehaviorexistsamongclients,withsomeclientsrevisitingnamesfrequentlyandothersqueryingalargersetofnameswithlessfrequency.

7RelatedWorkModelsofvariousprotocolshavebeenconstructedforunderstanding,simulat-ingandpredictingtrac(e.

g.

,[13]foravarietyoftraditionalprotocolsand[2]asanexampleofHTTPmodeling).

Additionally,thereispreviousworkoncharacterizingDNStrac(e.

g.

,[11,6]),whichfocusesontheaggregatetracofapopulationofclients,incontrasttoourfocusonindividualclients.

Finally,wenote—aswediscussin§1—thatseveralrecentstudiesinvolvingDNSmakeassumptionsaboutthebehaviorofindividualclientsorneedtoanalyzedataforspecicinformationbeforeproceeding.

Forinstance,theauthorsof[5]modelDNShierarchicalcacheperformanceusingananalyticalarrivalprocess,whilein[14],theauthorsusesimulationtoexplorechangestotheresolutionpath.

BothstudieswouldbenetfromagreaterunderstandingofDNSclientbehavior.

8ConclusionThisworkisaninitialsteptowardsrichlyunderstandingindividualDNSclientbehavior.

Wecharacterizeclientbehaviorinwaysthatwillultimatelyinformananalyticalmodel.

WendthatdierenttypesofclientsinteractwiththeDNSindistinctways.

Further,DNSqueriesoftenoccurinshortclustersofrelatednames.

Asasteptowardsananalyticalmodel,weshowthattheclientqueryarrivalprocessiswellmodeledbyacombinationoftheWeibullandParetodistributions.

Inaddition,wendthatclientshavea"workingset"ofnamesthatisbothfairlystableovertimeandfairlydistinctfromotherclients.

Fi-nally,ourhigh-levelresultsholdacrossbothtimeandqualitativelydierentuserpopulations—studentresidentialvs.

Universityoce.

Thisisaninitialindicationthatthebroadpropertiesweilluminateholdthepromisetobeinvariants.

References1.

OpenDNS.

http://www.

opendns.

com/.

2.

P.

BarfordandM.

Crovella.

GeneratingRepresentativeWebWorkloadsforNet-workandServerPerformanceEvaluation.

InACMSIGMETRICS,1998.

3.

T.

Callahan,M.

Allman,andM.

Rabinovich.

OnModernDNSBehaviorandProperties.

ACMSIGCOMMComputerCommunicationReview,July2013.

4.

M.

Ester,H.

-P.

Kriegel,J.

Sander,andX.

Xu.

ADensity-BasedAlgorithmforDiscoveringClustersinLargeSpatialDatabaseswithNoise.

InAAAIInternationalConferenceonKnowledgeDiscoveryandDataMining,1996.

5.

N.

C.

FofackandS.

Alouf.

ModelingModernDNSCaches.

InACMInternationalConferenceonPerformanceEvaluationMethodologiesandTools,2013.

6.

H.

Gao,V.

Yegneswaran,Y.

Chen,etal.

AnEmpiricalRe-examinationofGlobalDNSBehavior.

InACMSIGCOMM,2013.

7.

P.

Gauthier,J.

Cohen,andM.

Dunsmuir.

TheWebProxyAuto-DiscoveryPro-tocol.

IETFInternetDraft.

https://tools.

ietf.

org/html/draft-ietf-wrec-wpad-01(workinprogress),1999.

8.

WebsitesUsingGoogleAnalytics.

http://trends.

builtwith.

com/analytics/Google-Analytics.

9.

GoogleSafeBrowsing.

https://developers.

google.

com/safe-browsing.

10.

HTTPArchive.

http://httparchive.

org.

11.

J.

Jung,A.

W.

Berger,andH.

Balakrishnan.

ModelingTTL-BasedInternetCaches.

InIEEEInternationalConferenceonComputerCommunications,2003.

12.

R.

L.

Mattson,J.

Gecsei,D.

R.

Slutz,andI.

L.

Traiger.

EvaluationTechniquesforStorageHierarchies.

IBMSystemsJournal,1970.

13.

V.

Paxson.

EmpiricallyDerivedAnalyticModelsofWide-AreaTCPConnections.

IEEE/ACMTransactionsonNetworking,1994.

14.

K.

Schomp,M.

Allman,andM.

Rabinovich.

DNSResolversConsideredHarmful.

InACMWorkshoponHotTopicsinNetworks,2014.

- activityopendns相关文档

- prexopendns

- snapopendns

- randomopendns

- temsopendns

- similaropendns

- Usageopendns

亚洲云Asiayu,成都云服务器 4核4G 30M 120元一月

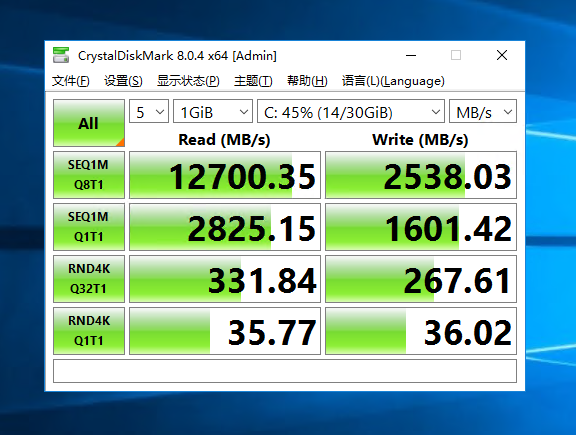

点击进入亚云官方网站(www.asiayun.com)公司名:上海玥悠悠云计算有限公司成都铂金宿主机IO测试图亚洲云Asiayun怎么样?亚洲云Asiayun好不好?亚云由亚云团队运营,拥有ICP/ISP/IDC/CDN等资质,亚云团队成立于2018年,经过多次品牌升级。主要销售主VPS服务器,提供云服务器和物理服务器,机房有成都、美国CERA、中国香港安畅和电信,香港提供CN2 GIA线路,CE...

妮妮云香港CTG云服务器1核 1G 3M19元/月

香港ctg云服务器香港ctg云服务器官网链接 点击进入妮妮云官网优惠活动 香港CTG云服务器地区CPU内存硬盘带宽IP价格购买地址香港1核1G20G3M5个19元/月点击购买香港2核2G30G5M10个40元/月点击购买香港2核2G40G5M20个450元/月点击购买香港4核4G50G6M30个80元/月点击购买香...

舍利云30元/月起;美国CERA云服务器,原生ip,低至28元/月起

目前舍利云服务器的主要特色是适合seo和建站,性价比方面非常不错,舍利云的产品以BGP线路速度优质稳定而著称,对于产品的线路和带宽有着极其严格的讲究,这主要表现在其对母鸡的超售有严格的管控,与此同时舍利云也尽心尽力为用户提供完美服务。目前,香港cn2云服务器,5M/10M带宽,价格低至30元/月,可试用1天;;美国cera云服务器,原生ip,低至28元/月起。一、香港CN2云服务器香港CN2精品线...

opendns为你推荐

-

支持ipad平台操作使用手册化学品安全技术说明书地址163tcpip上的netbios网络连接详细信息上的netbios over tcpip是什么意思?google图片搜索谁能教我怎么在手机用google的图片搜索啊!!!icloudiphone苹果手机显示"已停用,连接itunes"是什么意思联通合约机iphone5iphone5联通合约机是怎么回事fastreport2.5罗斯2.5 现在能卖多少啊!?!!!android5.1安卓系统5.1好吗