preletmecry

letmecry 时间:2021-01-15 阅读:()

BEJ.

Macroecon.

2016;16(1):145–170ContributionsSerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerument*Creditchannelandcapitalflows:amacroprudentialpolicytoolEvidencefromTurkeyDOI10.

1515/bejm-2015-0052PreviouslypublishedonlineAugust26,2015Abstract:Rapidcreditgrowthinducedbysuddencapitalinflowsmaynegativelyaffectacountry'seconomicperformance,withtheresultingoutflowsturningintoafinancialcrisis.

ThepurposeofthisstudyistodeterminewhethercontrollingthecreditchannelofmonetarypolicycouldbeusedasamacroprudentialtooltosuppresstheeffectsofsuddencapitalinflowsoneconomicperformanceforsmallopeneconomieslikeTurkey.

Inthispaper,usingtheVectorAutoregres-sionmethodologyemployedby(Bernanke,S.

B.

,M.

Gertler,andM.

Watson.

1997.

"SystematicMonetaryPolicyandtheEffectsofOilPriceShocks.

"BrookingsPapersonEconomicActivity1:91–157),weinvestigatewhethershuttingdownthecreditchannelhelpsreducetheeffectsofcapitalinflows.

Indeed,empiricalevi-dencefromTurkeyshowsthatdoingsodecreasestheeffectsofcapitalinflowsonimportsandindustrialproduction,butfurtherdecreasesinterestrateandpricesandfurtherappreciatesthedomesticcurrency.

Therefore,itmaybeprudenttosupportcreditcontrolwithadditionalpolicytoolstopreventafurtherdecreaseininterestrateandpricesandafurtherappreciationofthedomesticcurrency.

Keywords:capitalflows;creditchannel;macroeconomicprudentialpolicy.

JELCodes:E51;E52;E58.

1IntroductionCapitalinflowsasportfolioinvestmentsmayaffectacountry'seconomicper-formanceadverselybecauseoftheexternalfragilityofthedomesticfinancial*Correspondingauthor:M.

HakanBerument,DepartmentofEconomics,BilkentUniversity,06800,Ankara,Turkey,Phone:+903122902342,Fax:+903122662529,e-mail:berument@bilkent.

edu.

trSerdarVarlik:DepartmentofEconomics,HititUniversity,19040,Corum,Turkey146SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerumentmarket,especiallyifachievedthroughthebankingsystemwheninflowedcapitalturnstooutflowedcapital.

Thiseffectoneconomicperformance,frequentlyworkingthroughthecreditchannel,precipitatesfluctuationsinbanks'balancesheetsandmaydecreasecreditquality.

Moreover,currencyappreciationmaydamagepricestabilityandaggravatethecurrentaccountdeficitwithintheframe-workoffinancialstability.

Sincethe2008globalfinancialcrisis,themagnitudeofcapitalflowshasbecomeafactorinthefinancialstabilityofsmallopenecono-mies.

Suchcountries,includingTurkey,havebeguntoadoptvariousmacropru-dentialpolicytoolstopreventtheadverseeffectsofcapitalinflows;controllingbankcreditgrowthisonesuchtool.

Thispapercontributestotheliteratureonthesubjectbyprovidingevidenceforwhetherthecreditchannelcanbeusedasamacroprudentialtooltosuppresstheeffectsofsuddencapitalinflowsoneco-nomicperformanceforsmallopeneconomieslikeTurkey.

Suddencapitalinflowsmaycauseasurplusincreditsupply,looseningcreditstandardsandthusresultinginexcessivecreditgrowth(alsocalledacreditboom).

Thissituationcanthreatenpricestabilityandfinancialstabilitybyenlargingcurrentaccountdeficits,buoyingassetpricesandincreasingdomes-ticdemand.

Suddencapitalinflowsalsoincreasethebankingsector'sforeign-currency-denominatedliabilities(Gourinchas,ValdesandLanderretche2001;ElekdaandWu2011;Magudetal.

2012).

Adversely,aslowdowninshort-termcapitalinflows,suchasiftheeconomyencountersthesuddenstopproblem,maydamageeconomicperformancethroughthecreditchannelandevenresultinafinancialcrisis(Calvo1998;ReinhartandCalvo2000).

Barajas,Dell'Ariccia,andLevchenko(2009)callthisscenarioabadcreditboom,anditoccursbecausecentralbanks,especiallyindevelopingcountries,focusontheexcessivecreditgrowthwithoutplanningfortheproblemsthatcanoccurwhensuddencapitalinflowsstop.

Interestrate,whichisusedasthebasicmonetarypolicytoolbycentralbanksunderaconventionalpolicysettinginsmallopeneconomies,maynotbethebesttooltocontrolcredit.

Forexample,whencentralbanksinthesecoun-triesincreasethepolicyinterestratetocooldowntheeconomyandslowcredits,capitalflowsandcreditsincrease,stimulatingtheeconomy.

Thus,stirringupcapitalinflowsfeedscreditsratherthanconstrainingthem(Hahmetal.

2012).

Thisresultissimilartoanotherdilemma,thatis,whencentralbanksdecreasethepolicyratetodiscouragecapitalinflows.

Alowerinterest-ratepolicymaysparktheassetpricebubble,whichcausescredit-drivenand/orirrationalexuberance(seeMishkin2010).

Lowinterestratesmayalsoresultinexcessiverisktakingintheeconomy,thechannelcalledthe"risk-takingchannelofmonetarypolicy"(BorioandZhu2008,p.

iii).

Alowinterest-ratepolicycancauseanincreaseinthenetinterestratemarginforfinancialinstitutions,whichprovidesmoreprofitCreditchannelandcapitalflows147(AdrianandShin2010),andtherefore,theseinstitutionsmaychoosetoincreasetheleverageratioandsotakeonmoreriskyinvestments,whichincreasesassetprices,loosenscreditsandprecipitatesafinanciallyunstableenvironment.

Thereby,onitsown,interestratemaynotbeaneffectivepolicytooltostabi-lizethefinancialsystem.

Theseemergingdeficienciesinconventionalmonetarypolicysincetheglobalfinancialcrisismaysuggestusingalternativemacropru-dentialpolicytoolsthatcomplementthepolicyratetoolinanunconventionalmonetarypolicyframework.

TheTurkisheconomyprovidesaconvenientenvironmentinwhichtostudytheeffectofcreditcontroloncapitalflowineconomicperformance.

Thecreditchannelisawell-recognizedmethodofusingmonetarypolicytoaffecteco-nomicperformance(seeMishkin1996;Boivin,Kiley,andMishkin2010),andaveryimportantchannelforsmallopeneconomieslikeTurkey.

1Thepurposeofthispaperisnottodocumenttheexistenceorworkingsofthecreditchannelbuttoassesswhethercontrollingthecreditsofthedomesticbankingsystemdecreasestheeffectsofcapitalinflowsonasmallopeneconomy.

Hence,weanalyzetheimpactsofcapitalflowshocksontheeconomicperformanceoftheTurkisheconomythroughthecreditchannelbyusingBernanke,GertlerandWat-son's(1997)VectorAutoregression(VAR)methodology.

TheempiricalevidencegatheredfromtheTurkishcasesuggeststhatshuttingdownthecreditchanneldecreasestheeffectsofcapitalinflowsonimportsandindustrialproduction,butfurtherappreciatesthedomesticcurrencyanddecreasespricesandinterestrates.

Therefore,wesuggestthatcreditcontrolsmightbeonlyoneofasetoftoolsinmacroprudentialpolicytosuppresstheadverseeffectsofcapitalflows.

Turkeyachievedexternalfinancialliberalizationin1989,andsincethen,therelationshipbetweensuddencapitalinflowsandcreditgrowthhasbeengrowingstronger,threateningfinancialstability.

BaandKara(2011)(gover-norandchiefeconomistoftheCentralBankoftheRepublicofTurkey(CBRT),respectively),zatay(2011)(formerCBRTdeputygovernorandformermemberoftheCBRT'sMonetaryPolicyCommission),AkkayaandGürkaynak(2012)(twoacademicians)andKara(2012)statethatsuddencapitalinflowsdramaticallybringabouttwoimportantresultsforTurkey:excessivecreditgrowthandcur-rencyappreciation.

TheCBRTadmitsthatthesetwofactorsasaresultofcapitalinflowsmayresultinpriceinstabilityandfinancialinstability.

TheCBRT(2012a)andAlper,Kara,andYrükolu(2013)indicatethatrapidcurrencyappreciationinducedbycapitalinflowsmayaffectfirms'willingnesstoborrow,leadingtoan1InTurkey,thefinancialsystemischaracterizedbylowfinancialcapitalizationintheequitymarket,lowsecuritizationandlowopportunitiesforrefinancing(suchasforhousingrefinancing).

Forthisreason,thebankingsystemplaysabigroleinthecreditmarket.

148SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerument2See,forexample,BernankeandBlinder(1992),Sims(1992),GertlerandGilchrist(1994),BernankeandGertler(1995),Hubbard(1994),Cecchetti(1999),KishanandOpiela(2000),KashyapandStein(2000),Ashcraft(2006),Fuinhas(2008)andevikandTeksz(2012).

IntheTurkishcase,Gündüz(2001),engnülandThorbecke(2005),Arena,Reinhart,andVasquez(2007),Brooks(2007),Demiralp(2008),Cambazolu,andGüne(2011)andAlper,Hülagu,andKele(2012)arguethatusingthecreditchannelformonetarypolicyoperatesefficientlyinTurkey,butavuolu(2002),iek(2005)andAydinandIgan(2010)donotagree.

excessivelendingappetiteinbanks.

Thus,thebankingsectorincreasescreditstotheprivatesectorexcessively,whichcausesdomesticdemandtogrowfasterthanaggregateincome.

Thisprocessiscalledafinancialacceleratormechanism,andamplifiesbusinesscycles.

Eventually,thecurrentaccountdeficitdramati-callyincreases,inparallelwithcreditboomsandcurrencyappreciation,whichresultsinmacroeconomicinstabilityandevenfinancialcrisis(Ganiolu2012).

Anunforeseeableincreaseincreditgrowthandcurrencyappreciationinducedbyintensivesuddencapitalinflows(alsocalledhotmoney)negativelyaffectthecurrentaccountbalance.

Forexample,in2010,CBRTgovernorYlmazestimatedthata5%increaseincreditgrowthwouldtriggera2.

1%increaseinthecurrentaccountdeficitinTurkeyfortheyear2011(Ylmaz2010).

Therefore,controllingexcessivecreditgrowthmayforestallahighcurrentaccountdeficit.

AkayandOcakverdi(2012)alsosuggestthatcontrollingexcessivecreditgrowthmaysig-nificantlyreduceTurkey'shighcurrentaccountdeficit.

AccordingtoKaraetal.

(2014),anaverageannualcreditgrowthof15%forTurkeywouldbereasonableinthemediumterm.

InthesummaryofitsMonetaryPolicyCommitteeMeetingofJanuary29,2013,theCBRTstatedthat"[m]acroprudentialmeasureswillcontinuetobetaken,should…creditgrowthexpectationsexceed15%foralongperiod.

"Thereissubstantialempiricalresearchanalyzingthevalidityofthecreditchannelformonetarypolicy.

2Therelatedliteratureisenlargedwiththeroleofcapitalflowshocksoncredits,especiallyfordevelopingcountries.

Thesestudiesfocusonthecreditgrowthinducedbycapitalinflows(see,forexample,Gourinchas,ValdesandLanderretche2001;TornellandWestermann2002;Duenwaldetal.

2005).

Thisliteraturehasbeengrowingrapidlysincetheglobalfinancialcrisis:MendozaandTerrones(2008),BakkerandGulde(2010),Borioetal.

(2011),Shin(2012),CetorelliandGoldberg(2012)andLaneandMcQuade(2013)allpointoutthatcapitalflowsandinternationalliquiditydeterminefluc-tuationsincredits(boomandbusts)throughthecreditchannelandthusdeter-mineeconomicperformance.

Allauthorsunderlinetheadverseeffectsofcreditgrowthinducedbysuddencapitalinflows,andtheTurkishcasehasplentyofevidenceshowingthisrelationship(seeAlperandSalam2001;AslanandKorap2007;ToganandBerument2011;BiniciandKksal2012).

Creditchannelandcapitalflows149Thispaperisorganizedinsixsections.

InSectionII,webrieflyexplaintherelationshipamongcapitalflows,creditsandthecurrentaccountbalanceinTurkey.

InSectionIII,weoutlinethemethodologyemployedtoassesstheeffectofshuttingdownthecreditchannel.

SectionIVpresentstheempiricalevidenceunderalternativescenarios.

SectionVprovidesasetofrobustnessanalysesandSectionVIconcludesthepaper.

2TherelationshipbetweencapitalflowsandcreditsinTurkey:ashortstoryThebankingsectorplaysanimportantroleinthefinancialmarket,especiallyfordevelopingcountriessuchasTurkey,duetothesector'sbiggershareinthewholefinancialsystemcomparedtodevelopedcountries;banksnotonlydeterminefinancialdeepeningandbutalsotheefficiencyofmonetarypolicy(seeCecchetti1999).

IntheTurkishcase,thebankingsector'sshareofthebalancesheetinthefinancialsystemwas91.

5%in2004and87.

6%in2012(CBRT2005,2013).

Althoughthesharewaslowerin2012,thebankingsectorremainshighlydominantoverall;whilethepercentageassetshareofthebankingsectorintheGDPwas71.

2%in2004,thisratioreached98%in2012(BankingRegulationandSupervisionAgency2006,2012).

Therefore,thecreditchannel,especiallythebanklendingchannel,isimportantfortheTurkisheconomy.

Sincetheintroductionofstructuralreformsin2001,thecreditchannelhasbeenworkingmoreefficientlythanothermonetarypolicytransmissionmechanisms(Ba,zel,andSarkaya2007).

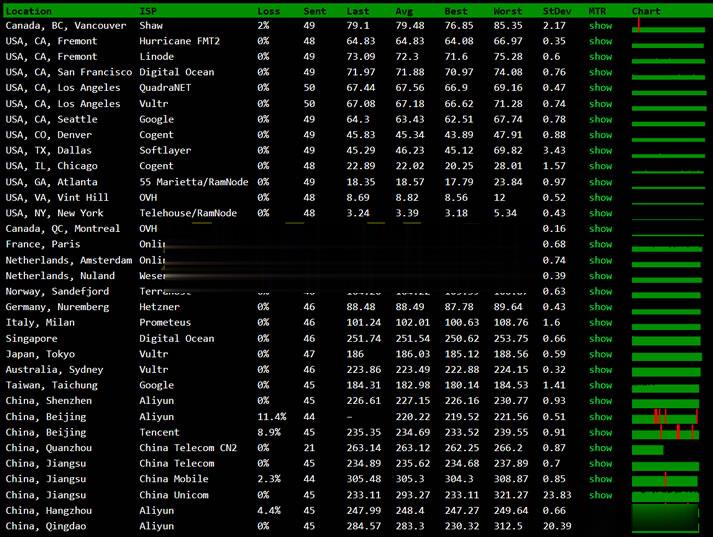

Toassesstheimportanceofcreditgrowth,wefirstprovideasetofdescrip-tivestatistics(Table1).

Thetableshowsahighcorrelationbetweencreditsandeconomicperformance,whichsuggeststheimportanceofthecreditchannel.

Thecorrelationcoefficientsbetweencreditsandimports,betweencreditsandindus-trialproductionandbetweencreditsandconsumerpriceindexaremorethan0.

85.

Furthermore,thecorrelationcoefficientbetweencreditsandcapitalflowsis0.

66,whichshowsthecloserelationshipbetweencreditsandcapitalflows.

Figure1showstherelationshipbetweencreditsandcapitalflows,andbetweencreditsandthecurrentaccountdeficit.

Whilerealcreditgrowthandcapitalandfinancialaccountsmovetogether,realcreditgrowthandthecurrentaccountdeficitmoveintheoppositedirectionfromeachother.

Todetectthefundamentalrelation-shipbetweencreditsandcapitalinflowsinTurkey,wefocusontheyearssinceexter-nalfinancialliberalization(1989onward).

Respectively,increasesanddecreasesinrealcreditgrowthhavebeenaccompaniedbycapitalinflowsandoutflowssincethe1990s.

AsevidentinFigure1,duringthe1994financialcrisis,whileincrease150SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerumentinrealcreditfirstslowedandthendecreaseddependingoncapitaloutflows,thecurrentaccountdeficitalsodecreasedandthussodidthecurrentaccountsurplus.

Similarly,the1998AsianfinancialcrisisinducedcapitaloutflowsfromTurkeybecauseofdecreasedglobalriskappetite.

Thesecapitaloutflowsledtodecreasesinrealcreditgrowthandcurrentaccountdeficits.

Thisstoryamongcapitalflows,creditsandcurrentaccountshasrepeatedlyplayedoutinTurkey,especiallysince1999.

Whencapitalinflowsinthepre-financial-crisisperiodturnedintocapitalout-flowsduringtheNovember2000andtheFebruary2001financialcrises,realcreditgrowthdramaticallycontracted,andcorrespondingly,acurrentaccountsurplusemerged.

InApril2001,thegovernmentannouncedtheTransitiontoaStrongEconomyProgram,whoseaimsincludedbankingsectorsoundness,pricestabil-ityandloweredfiscaldominance;an(implicit)inflationtargetingstrategybeganinJanuary2002.

Alsoin2002,theBanks'AssociationofTurkeyandtheBankingRegulationandSupervisionAgency(BRSA)announcedtheIstanbulApproach,Table1:Correlationcoefficentsbetweennominalandrealcreditsandothervariables.

CapitalandfinancialaccountHotmoneyExchangeratebasketInterbankrateImportsIndustrialproductionConsumerpriceindexCurrentaccountbalanceNominalcredit0.

660.

540.

76–0.

510.

910.

850.

88–0.

80Realcredit0.

660.

520.

74–0.

500.

930.

870.

87–0.

82Source:CBRT.

–2–1.

5–1–0.

500.

511.

522.

51992Q11993Q31995Q11996Q31998Q11999Q32001Q12002Q32004Q12005Q32007Q12008Q32010Q12011Q32013Q1Capitalandfinancialaccount/GDPRealcreditgrowth/GDPCurrentaccountdeficit/GDPFigure1:TheRelationshipbetweenrealcreditgrowthandbalanceofpayment.

Source:CBRT.

Creditchannelandcapitalflows151whichengagedinareconstructionoffirms'credits.

In2005,BankingLawNo.

5411wasenacted,coveringprudentialregulationsforbanks'creditstandards.

Asaresultofthesemeasures,capitalinflowstoTurkeyincreased;correspondingly,realcreditgrowthincreasedandthecurrentaccountdeficitdrasticallyincreased.

Meanwhile,inDecember2006andFebruary2008,theBRSAincreasedgeneralprovisionsforloansinordertocontrolthecreditriskcarriedbythebankingsector'sbalancesheet.

Whenweanalyzetheperiodsincethe2008globalfinancialcrisis,weseethatadecreaseinglobalriskappetiteandanincreaseinTurkey'sriskpremiumprimarilyslowedcapitalinflowstoTurkey,buttheninitiatedcapitaloutflows.

Throughout2009,realcreditgrowthrapidlydecreased,whichcausedadecreaseinthecurrentaccountdeficit.

Nevertheless,theCBRT'smonetarypolicies(suchasreducingthepolicyrateandthereserverequirementratioafter2008)andtheincreasedcapitalinflowsasaresultofsoaringgloballiquidity,inducedespeciallybytheUSFederalReserve'sQuantitativeEasing-IIpolicy,reinitiatedanincreaseinrealcreditgrowthatthebeginningof2010.

Thereupon,withintheframeworkofitsMonetaryPolicyExitStrategy,implementedinApril2010,theCBRTbegantoincreasereserverequirementratiostopreventrapidcreditgrowth.

RememberthattheCBRTdeterminesthedifferentreserverequirementratiosfordomestic-andforeign-currency-denominateddeposits.

Inthisway,itaimstoincreasetheefficiencyofthereserverequirementratio3(BaandKara2011;Kara2012).

InSeptember2010,theCBRTterminatedinterestpaymentsforreserverequirementsdenominatedbydomesticcurrency.

Then,inDecember2010,theCBRTdifferenti-atedreserverequirementratiosfordepositsatdifferentmaturities,andexpandedthescopeofreserverequirements.

However,thisincreaseinreserverequirementratiosdidnotcurbcreditgrowth;conversely,creditgrowthdrasticallyincreasedandthecurrentaccountdeficitincreasedaswell.

4Therapidcreditgrowthonly3Ontheotherhand,theCBRThasbeenalteringtheframeworkofitsmonetarypolicysincethelastquarterof2010byusingnewmonetarypolicytoolssuchasanasymmetricinterestratecorri-dorandthereserveoptionmechanism(ROM)topreventthedomesticeffectsofexternalfragility,suchasexcessivecreditgrowthandcurrencyappreciationinducedbysuddencapitalinflows(CBRT2011;Akeliketal.

2013).

ThisnewapproachinvolvedaparadigmshiftinmonetarypolicypracticeforTurkey(er2011).

4zatay(2011)ascribesthefailureofthereserverequirementpolicytocontrolcreditgrowthtothebankingsystem'sclosesubstitutionrelationshipsregardingliabilitiesmaturities.

AkkayaandGürkaynak(2012)agree;theirstudysuggeststhatthereserverequirementpolicyfailedbecausewhentheCBRTincreasedreserverequirementratios,bankssteeredtowardsnon-depositfundssuchasforeignswapstofinancecredits.

Therefore,notonlydidthechange-of-deposit-to-total-assetratioincrease,butsodidthecredits-to-total-assetratio.

er(2011)andzatay(2012)maintainthatastheCBRTincreasedreserverequirementratios,bankscompensatedbydimin-ishingliquiditybyagainborrowingfromtheCBRT'sopenmarketoperations.

Inthatcase,thereserverequirementpolicywasnotanefficienttoolforreducingcredits.

152SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerumentbegantoslowaftertheBRSAimplementedamicroprudentialpolicytosupporttheCBRT'smacroprudentialpolicy,increasingtherateofitsResourceUtilizationSupportFundandLoan-to-Valueratio(CBRT2012b).

Asaresultoftheongoingslowdownintheglobaleconomy,andbecauseofthecombinedeffortsoftheCBRTandtheBRSA,creditgrowthcamedownto"reasonablelevels"bytheendof2012(CBRT2012b,p.

iv).

Furthermore,theCBRT(2012a)determinedthetargetsforanaverageannualrateofincreaseincreditgrowthtobe15%,whichreflectedthecreditruleformonetarypolicyin2013.

Thus,ontheonehand,theCBRTbegantouseanasymmetricinterestratecor-ridorsystemtodiscouragecapitalinflowsandtopreventanannualcreditgrowthofmorethan15%,andontheotherhand,itimplementedtheROMandreserverequirements,respectively,toprovidecurrencyandcreditgrowthstability.

Con-trollingcreditgrowththusplaysalargepartintheCBRT'snewmonetarypolicyframeworkintermsofpricestabilityandfinancialstability.

3MethodologyInthissection,wefirstintroducethebenchmarkVARspecificationthatweusetoassesstheeffectsofcapitalflowsoneconomicperformance.

Later,weoutlinehowtheeffectsofcapitalflowsoneconomicperformancearegatheredbykeepingthecreditlevelconstant.

ThebenchmarkVARspecificationistheregularVARspecification,whichincludesvariablesasameasureofcapitalflow,exchangerate,interestrate,credits,imports,incomeandprices.

Weusealagorderoftwo,assuggestedbytheBayesianInformationCriteria(BIC).

Weinclude11monthlydummiestoaccountforseasonality.

Moreover,toaccountforfinancialcrisisperiods,weincludeinter-ceptdummiesforeachperiodfromthesecondtothefifthmonthsof1994,theeleventhmonthof2000andthesecondmonthof2001.

Toidentifycapitalflowshocks,weemploytheCholeskydecomposition;thus,theorderofvariablesisimportant.

Allvariableplacementsareaffectedbytheprecedingvariablescontemporaneouslybutarenotaffectedbythelattervari-ablescontemporaneously.

However,allthevariablesaffecteachotherwithalag.

Thevariablesareorderedascapitalflowmeasure,exchangerate,interestrate,credits,imports,industrialproductionandconsumerpriceindex.

Thus,capitalflowmeasuresaffectcapitalflowmeasures,exchangerate,interestrate,credits,imports,industrialproductionandconsumerpriceindexcontemporaneouslybutarenotaffectedbythesevariablescontemporaneously.

Similarly,exchangerateisaffectedbycapitalflowscontemporaneouslyandaffectssubsequentvariablesCreditchannelandcapitalflows153contemporaneously.

However,again,allofthesevariablesaffecteachotherwithalag.

Theorderofvariablesmustbediscussed.

Turkeyisasmallandopeneconomy.

Ithasavolatilemarket,andfor2011,attractedonly0.

059%5ofthetotalcapitalflowsto30emergingmarketsconsideredbytheInstituteofInternationalFinance(IIF),eventhoughitistheeighteenth-largesteconomyintheworldaccordingtotheWorldBank.

Thus,Turkeyisasmallplayeringlobalcapitalflowmarkets.

ItisnotthatTurkey'seconomicperformanceaffectscapitalflowstoTurkey,butthatcapitalflowsaffectTurkey'seconomicperformance,possiblyduetothecountry'squestionablepolicyframeworksandpreviouspoliticaluncertainties(IIF2014).

Thus,weordercapitalflowsfirst.

Forcapitalflowstoaffectthedomesticeconomytheyneedtobeconvertedtodomesticcurrency,becausebytheirnature,capitalflowsareinforeigncurrency.

Thus,weplaceexchangeratesecond.

Thethirdvariableisshort-terminterestrate,whichtheCBRTconsidersapolicytool(see,forexample,Berument2007;lkeandBerument2014).

Weplaceinterestratebeforecredits,imports,outputmeasureandprices.

Thisorderingsuggeststhattheconductofmonetarypolicyaffectstheseeconomicvariablescontemporane-ously.

Placinginterestrateafterthesevariableswouldhaveassumedtheextremeinformationassumption,whichwouldhavesuggestedthattheCBRTknewthesemacrovariablesforagivenmonth.

OurorderingisparalleltoLeeper,Sims,andZha(1996)andSimsandZha(2006).

Sinceweconsidercreditcontrolasamon-etarypolicytool,weplacecreditsjustafterinterestrateandbeforeimports.

Placingcreditsbeforeimportsisparallelwiththeargumentthatcreditexpansionincreasesthecurrentaccountdeficitthroughhigherimportdemand(seeIMF2012;Aysan,Fendolu,andKln2014).

WeplacetheimportmeasurebeforetheoutputmeasurebecauseTurkeyisasmallopeneconomywithhighenergyinputsandrawandintermediateproductimportdemandsforitsproduction.

Thisorder-ingisparalleltoSvensson(1998)andLeitemoandSderstrm(2001).

Thelasttwovariablesareoutputandprices.

Sincepricesrespondslowerthanoutput,weplaceoutputbeforeprices.

Toassesstheeffectsofcapitalflowsoneconomicperformancewhenthereisnocreditgrowth,weemploytheVARmethodologyusedbyBernanke,GertlerandWatson(1997).

TheyinvestigatethedirectandindirecteffectsofoilpriceshockonaneconomybyconsideringasmallVARsystem,followingpolicyalternativesregardinghowthemonetarypolicymeasureoftheFederalFundsRaterespondstooilshocksundervariousscenarios.

Usingourvariablesintheiralternativepolicysimulations,weconsidertwoscenarios.

Firstisthebasescenario,where5Authors'calculationfromInstituteofInternationalFinancedata(2013)andtheCBRT'sElec-tronicDataDeliverySystem(EDDS).

154SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerumentthecontrolpolicyvariable(interestratesintheirspecificationandcreditinourspecification)respondstodevelopmentsintheeconomyandwherethecontrolpolicyvariableaffectseconomicperformancecontemporaneouslyorwithlags,dependingontheidentificationassumptions:thismodelisbasicallytheconven-tionalunrestrictedVARmodel.

Thealternativepolicyscenarioisthatthecreditvariabledoesnotrespondtoanymacroeconomicvariablethatweconsider.

Thus,wecanassesshowcapitalflowsaffecteconomicperformanceifpolicyauthoritiescankeepthecreditlevelconstant.

FollowingBernanke,GertlerandWatson(1997),wecanwriteourspecifica-tionas:ΠΠΠεεε=1()ptcfcfiticfYiticfcriticftcryiytcrcrcrtiCFCFYCreditGG(1)ΠΠΠεεε=1()ptycfitiyyitiycitiyccftyyYtycrcrtiYCFYCreditGGG(2)ΠΠπεεε=()ptcrcfticyiticrcrticrcfcftcytytcrtiiCreditCFYCreditGG(3)CFtisthecapitalflowvariable,CredittisthecreditvariableandYtisthevectorforalltheothermacroeconomicvariablesthatweconsider.

TheorderandzeroconstraintsoftheGmatricesaredeterminedbytheidentificationassumptions.

6ThebasescenariodoesnotimposeanyconstraintwhentheimpulseresponsesaregatheredontheΠmatrixes.

Underthealternativescenario,werestrictΠcrcf,i,Πcry,i,GcrcfandGcrytozero.

4EmpiricalresultsWeusemonthlydatafortheperiodbetweenJanuary1992andMay2013.

AlthoughtheCBRTannouncedthattheyhavetriedtolimitcreditgrowthtocontrolcapitalflowssince2010,itiscommonforTurkishpolicymakerstointerveneinbanks'creditlimits,asevidentbystatementsmadebytheprimeministerjustafterthe2008financialcrisisbegan,andbytheabove-mentionedIstanbulApproach.

Thus,oursamplestartsinJanuary1992,withtheonsetofthemonthlyavailabilityofdataoncurrentaccountbalances.

Inourdata,weusecapitalflowsfromthecurrentaccountbalanceforcapitalflows,overnightinterbankinterestrateforinterestrate,consumerpriceindex6UndertheCholeskydecomposition,Gcry,GcrcrandGycrarezeroandGyyisalowertriangularmatrix.

Creditchannelandcapitalflows155forprices,importsfromcurrentaccountforimportsandindustrialproductionforincome.

Totalcreditstotheprivatesectorareusedforcredits,whichconsistofcreditsextendedbyconventionalcommercial,investment,developmentandparticipationbanks.

WeusetheTurkishLiravalueofthebasketof1USDollar+1Euro7astheexchengerate.

ThecapitalflowandimportvariablesaredeflatedwiththelagvalueoftheinterpolatedmonthlyGDPtonormalizethembeforeusingthemintheanalyses.

WeusethelagvalueofGDPtoavoidsimultaneity,thatis,sothatothervariablesdonotaffectthecurrentaccountbalancethroughGDP.

Allthesevariablesenterthesysteminlogarithmsexceptinterbankinterestrate,importsandcapitalflowmeasures.

AlldatausedinthisstudyaregatheredfromtheCBRT'sEDDS.

Figure2reportstheimpulseresponsefunctionswhenaone-unitshockisgiventocapitalflowsforthetwotypesofspecificationsthatweconsider.

However,toavoidmultiplelinesinthefigure,whichcouldbeconfusing,weonlyreporttheconfidenceone-standard-errorbandsforthebasescenario.

Wereporttheimpulseresponseswithouttheconfidencebandsforthealternativescenario.

Iftheimpulseresponsesofthealternativescenariocrosstheconfidencebandsofthebasescenario,thenwecansaythatunderthealternativescenario,theimpulseresponseschangeinastatisticallysignificantfashionfromthebasesce-nario.

Theconfidencebandsarereportedassolidlinesandtheimpulseresponsefunctionswithnocredit-growtheffectareplottedasdottedlines.

PanelAofFigure2reportshowaone-unitshocktocapitalflowsaffectsitselffor24periods.

Underthebasescenario,thiseffectispositiveandstatisticallysig-nificantfortwoperiods;theconfidencebandsarequitenarrowandtheimpulseresponsesunderthealternativescenarioarewithintheconfidencebands.

Theimpulseresponsesnotcrossingovertheconfidencebandsunderthealternativescenariosuggeststhatwecouldnotfindstatisticallysignificantlydifferentevi-denceforthebehaviorofcapitalflowsfromthebasescenario.

PanelBreportstheimpulseresponsesonhowtheexchangerateresponds.

Theconfidencebandssuggestthatcurrencyappreciatespermanently,andthiseffectisstatisticallysignificantforthe24periodsthatweconsiderunderthebasescenario.

Whencreditsarekeptconstant(thealternativescenario),currencyalsoappreciates.

Thelevelofappreciationishigherthanwhatthebasescenariosuggestsafterthefirstperiod.

Thedifferencebetweenthebasescenarioandthealternativescenarioisstatisticallysignificantbetweenthethirdandthirteenthperiods.

Thisresultmakessensebecauseshuttingdowncreditsdecreasesimportdemandmostlyforinvestmentgoodsandrawmaterials,andputslesspressure7TheEuroserieswasnotavailablebeforeJanuary1999,thusweusedthefixedexchangeratebetweentheEuroandtheDeutscheMarktocalculatetheEuroexchangerate.

156SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerumentD:Responseofcreditstoprivatesector00.

20.

40.

60.

81.

01.

205101520E:Responseofimport00.

010.

020.

030.

040.

050.

060.

0705101520F:Responseofindustrialproduction0.

050.

100.

150.

200.

250.

300.

350.

400.

450.

5005101520A:Responseofcapitalflows–0.

20.

00.

20.

40.

60.

81.

01.

205101520B:Responseofexchangeratebasket–0.

7–0.

6–0.

5–0.

4–0.

3–0.

2–0.

1–0.

005101520C:Responseofinterbankinterestrate–160–140–120–100–80–60–40–20005101520G:Responseofconsumerpriceindex05101520–0.

5–0.

4–0.

3–0.

2–0.

100.

1Figure2:Responsestocapitalflowsforthefullsample.

Thesolidblacklinesreportthelowerandupperboundsoftheconfidenceintervalofthebasescenario.

Thedashedlinerepresentstheimpulseresponsewhencreditleveliskeptconstant.

ontheexchangerate.

Thus,appreciationshouldbehigherunderazerocreditgrowthconstraint.

PanelCreportstheimpulseresponsesfortheinterbankinterestrates.

Themedianresponseofinterestrate,whichcanbefollowedbythemid-pointsoftheconfidencebandsofthebasescenario,staysbelowthepre-shocklevelandremainsthereforthe24periodsthatweconsider.

Thelowerinterestrateissta-tisticallysignificantforthe24periodsthatweconsider.

Theimpulseresponseunderthealternativescenariorevealsalowerinterestratethanthebasescenariobetweenthefirstandninthperiods.

Thiseffectisstatisticallysignificantbetweenthethirdandsixthperiods,whichmakessensebecauseshuttingdowncreditsmeansthatalowercreditdemandputslesspressureontheinterestratethanunderthebasescenario.

Therefore,weconsiderthatwhencreditsarekeptcon-stant,thereisagreaterdecreaseininterestrate.

Creditchannelandcapitalflows157PanelDreportstheimpulseresponsesofcreditswhenaone-unitshockisgiventocapitalflows.

Notethatwedonotreporttheimpulseresponseswhenthecreditleveldoesnotchange.

Underthebasescenario,creditsincreasewithapositiveshocktocapitalflows.

Thisincreaseisstatisticallysignificantforthe24periodsthatweconsider,assuggestedbytheconfidencebandsofthebasescenario.

PanelEreportstheimpulseresponsesforimports.

Importsincreasewithcapitalflows,andthisincreaseisstatisticallysignificantformostofthe24periodsthatweconsider.

Underthealternativescenario,afterthesecondperiod,importsarealwayslowerthanthemedianofimportresponsesunderthebasescenario.

Thedifferencebetweenthebasescenarioandthealternativescenarioisstatisti-callysignificantatthemarginbetweenthethirdandsixthperiods.

PanelFreportstheimpulseresponsesforindustrialproduction.

Theconfi-dencebandsunderthebasescenariosuggestthatindustrialproductionincreaseswithcapitalflows.

Thisincreaseisstatisticallysignificantforthe24periodsthatweconsider.

However,theincreaseinindustrialproductionislowerthanthemedianofthebasescenarioaftertheninthperiodunderthealternativescenario.

Thislowerincreaseinindustrialproductionisstatisticallysignificantafterthesixteenthperiod.

Thus,increaseinoutputislowerunderthealternativescenario.

PanelGreportstheimpulseresponsesforconsumerprices.

Underthebasescenario,untilthethirdperiod,consumerpriceindexdecreasesandisstatis-ticallysignificantbetweenthefirstandthirdperiods.

Afterthethirdperiod,theconfidencebandssuggestthatthiseffectisnotstatisticallysignificant;however,underthealternativescenariotheconsumerpriceindexisstatisti-callysignificantlylowerthanwhatthebasescenariosuggestsafterthethirdperiod.

Thus,whencreditleveliskeptconstantadecreaseinconsumerpriceindexishigher.

Insum,capitalflowswithoutcreditcontrolappreciatethedomesticcurrency,decreaseinterestratesandpricesbutincreaseimportsandoutput.

However,constrainingcreditgrowthdecreasestheeffectsofcapitalinflowsonimportsandindustrialproduction,butfurtherappreciatesthedomesticcurrencyanddecreasesinterestrateandprices.

Thereasonforthisresultmaybethatoncethecreditchannelisshutdown,importordersdecreaseforproductssuchasinvest-mentgoods,consumergoodsandothergoodsatagivenlevelofcapitalflow.

Thissituationwouldcreatelessdemandforforeignexchange,whichwouldresultinanappreciationofdomesticcurrency.

Thesameamountofcapitalflowcreatesmoredemandonbondswhenthereisalowerorderofimportdemand,andinter-estratedecreases.

Higherappreciationandlowerinterestratearealsoassociatedwithhigheroutput.

Last,pricesdecreasemoreduetoalowerexchangeratepass-throughandalowerdemandforimportedproducts.

158SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerumentFortheadoptionofcreditcontrolsasamacroprudentialpolicytool,weobserveafurtherappreciationofdomesticcurrencyandlowerinterestrateandprices,whichmightbeasourceofvulnerability.

Undercreditcontrol,however,vulnerabilityofthefinancialmarketmightnotbeanissuewithalowerinterestrate.

PricedeflationhasneverbeenaproblemforTurkey,butappreciationofdomesticcurrencyisawell-recognizedproblembytheCBRT,thegovernmentandthepublic.

Thus,additionalmacro/microprudentialpoliciesshouldlikelyalsobeemployedwithcreditconstrainttoavoidtheadverseeffectsofappreciation.

Inthepast,theCBRThasadoptedvariouspoliciestoavoidexcessiveappreciation,suchasincreasingforeignexchangedemandthroughahigherrequiredreserveratioforforeign-currency-denominateddepositsand/orincreasingtheROM,whichallowsdomesticbankstoholdpartofTurkish-Lira-denominatedliabilitiesatthecentralbankinforeigncurrency(fordetails,seeCBRT2012c;IMF2013).

Thus,ourfindingsareparallelwiththoseofBlanchard,Dell'AricciaandMauro(2013),whosuggestthatthepolicymakermayusevariouspolicytoolsbyharmo-nizingabroad-scopedbutinstantlyeffectivemonetarypolicyandmore-targetedfiscalmeasures.

Theyalsosuggestthatdevelopingcountriesusemacropruden-tialtoolstoaffectforeignexchangewhileadvancedcountriesusesuchtoolstoleadborrowerbehavior.

5RobustnessanalysesThissectionprovidesasetoffurtheranalysestoassessthevalidityoftheresultsgatheredfromFigure2underalternativeset-ups.

TheCBRTstatedthatitisnotonlythelevelofcurrentaccountdeficitbutalsoitsfinancingthatisaproblem.

Portfolioinvestmentortheabove-mentionedhotmoney,forexample,islessdesirablethanless-liquidfinancing(suchasforeigndirectinvestments)tofinancethecurrentaccountdeficit(CBRT2012a).

WerepeattheexerciseforcapitalflowswiththebroaddefinitionofhotmoneyfromLounganiandMauro(2000).

8TheresultsarereportedinFigure3,whichshowsthatthebasicinferencefromFigure2isrobust.

8LounganiandMauro(2000)definethreehotmoneymeasuresbasedonbalanceofpayment:HotMoneyI,HotMoneyIIandBroadHotMoney.

HotMoneyIconsistsofthesumofNetErrorandOmissions,OtherInvestment(Assets)andOtherInvestment(Liabilities)heldbyentitiesotherthanmonetaryauthorities,thegovernmentandbanks.

HotMoneyIIequalsHotMoneyIplusOtherInvestment(Assets)andOtherInvestment(Liabilities)heldbybanks.

BroadHotMoneyincludesHotMoneyIIplusNetFlowsofPortfolioInvestmentAssetsandLiabilitiesintheformofDebtSecurities.

Creditchannelandcapitalflows159Toidentifyshocksforeachmacroeconomicvariable,weusetheCholeskydecomposition,andtheorderofvariablesisimportant.

ToganandBerument(2011)arguethatcreditsdonotaffecteconomicperformancebutdorespondtoeconomicperformancecontemporaneously.

Toaccountforthissituation,weplacecreditslastintheordering.

Figure4reportsthecorrespondingimpulseresponses,andshowsthattheresultsfromFigure2arerobust.

Turkey'smostimportanteconomicproblemisthecurrentaccountdeficitanditsfinancing(BaandKara2011;Ba2012).

Aswediscussabove,Turkeyisasmallplayerininternationalfinance.

ThelackofTurkey'sfinancingoptionsanditsvolatilityaremostlyduetonon-economicfactorssuchasdomestic/regionalpoliticalinstability,worldcommoditypricevolatilityandworldliquidity(seeYlmaz2008;KlnandTun2014).

However,forthoroughness,weordercapitalD:Responseofcreditstoprivatesector00.

20.

40.

60.

81.

01.

21.

40246810121416182022E:Responseofimport00.

010.

020.

030.

040.

050.

060246810121416182022F:Responseofindustrialproduction0.

050.

100.

150.

200.

250.

300.

350.

400.

450.

500246810121416182022A:Responseofhotmoney00.

20.

40.

60.

81.

01.

20246810121416182022B:Responseofexchangeratebasket–0.

6–0.

5–0.

4–0.

3–0.

2–0.

100246810121416182022C:Responseofinterbankinterestrate–125–100–75–50–250250246810121416182022G:Responseofconsumerpriceindex0246810121416182022–0.

5–0.

4–0.

3–0.

2–0.

100.

1Figure3:Responsestohotmoneyforthefullsample.

Thesolidblacklinesreportthelowerandupperboundsoftheconfidenceintervalforthebasescenario.

Thedashedlinerepresentstheimpulseresponsewhencreditleveliskeptconstant.

160SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerumentflowslastintheVARsettingeventhoughthisisnotareasonableassumptionbecauseofTurkey'shighfragilityduetoitslowsavingsrate,weaklegalstructureandhighpoliticalrisk.

Thesudden-stopliteraturealsosuggeststhatfragilityinaneconomyaffectscapitalflows.

Thus,itismorelikelythatcapitalflowisanexog-enousratherthanendogenousvariableinTurkey,thatis,capitalflowsmaynotbeaffectingbutareaffectedcontemporaneouslybytheothersixvariablesthatweuseintheVARsetting.

9TherelevantimpulseresponsefunctionisreportedD:Responseofimport00.

010.

020.

030.

040.

050.

060.

070246810121416182022E:Responseofindustrialproduction0.

050.

100.

150.

200.

250.

300.

350.

400.

450.

500246810121416182022F:Responseofconsumerpriceindex–0.

5–0.

4–0.

3–0.

2–0.

100.

10246810121416182022A:Responseofcapitalflows00.

20.

40.

60.

81.

01.

20246810121416182022B:Responseofexchangeratebasket–0.

6–0.

5–0.

4–0.

3–0.

2–0.

100246810121416182022C:Responseofinterbankinterestrate–140–120–100–80–60–40–2000246810121416182022G:Responseofcreditstoprivatesector024681012141618202200.

20.

40.

60.

81.

01.

2Figure4:Shocktocapitalflowsrecordedvariable:creditorderedlast.

Thesolidblacklinesreportthelowerandupperboundsoftheconfidenceintervalforthebasescenario.

Thedashedlinerepresentstheimpulseresponsewhencreditleveliskeptconstant.

9Alowpersistencyofcapitalflowshocksintheanalyseswereportfurthersupportsourargu-mentthatcapitalflowsaremorelikelytobeexogenoustothesixvariablesthatweconsiderratherthanbeingendogenous.

Sinceourstudyexaminestheeffectofcapitalflowsoneconomicperformance,duetothenatureofthequestion,capitalflowshouldbeoneofthevariablesintheVARsetting.

Sinceitisthe'mostexogenous',itistheleastlikelyvariabletobeorderedlastandthemostlikelyvariabletobeorderedfirst.

Creditchannelandcapitalflows161inFigure5.

Thebasicfindingsofthepaperontherelativeeffectofcapitalflowswhencreditiscontrolledversusnotcontrolledarerobustevenifcapitalflowsarestatisticallyweaker.

Notethatevenundertheseassumptions,westillobservethatwhencreditsarecontrolled,theresponsesofexchangerate,interestrate,importandpricesdifferinastatisticallysignificantfashion.

10G:Responseofcapitalflows–0.

200.

20.

40.

60.

81.

01.

20246810121416182022D:Responseofimport–0.

0100.

010.

020.

030.

040.

050.

060.

070.

080246810121416182022E:Responseofindustrialproduction–0.

100.

10.

20.

30.

40.

50.

60246810121416182022F:Responseofconsumerpriceindex–0.

4–0.

3–0.

2–0.

100.

10.

20246810121416182022A:Responseofexchangeratebasket–0.

5–0.

4–0.

3–0.

2–0.

100.

10.

20246810121416182022B:Responseofinterbankinterestrate–120–100–80–60–40–2000246810121416182022C:Responseofcreditstoprivatesector00.

20.

40.

60.

81.

01.

20246810121416182022Figure5:Responsestocapitalflowswithcapitalflowsorderedlast.

Thesolidblacklinesreportthelowerandupperboundsoftheconfidenceintervalforthebasescenario.

Thedashedlinerepresentstheimpulseresponsewhencreditleveliskeptconstant.

10Inourspecification,exchangerateisorderedbeforeinterestrate.

However,inthepost-2008era,theCBRTusedinterestratetoreversecapitalflows.

Thus,itcanbearguedthatthereisacontemporaneousrelationshipbetweeninterestrateandexchangerate.

WelookedforrelevantStructuralVectorAutoregression(SVAR)specificationsintheliteraturethatwouldallowthisrelationshipbutcouldnotfindany.

WealsoexperimentedwithvariousSVARspecifications,butamongtheimpulseresponsesthatgaveresultsparalleltotheeconomictheoryforthebench-markmodel,wefoundnonethatgaveimprovedresults.

Thus,ourbasicconclusionsofthepaperremainrobust.

Sincethecontributionofthisavenuewasnil,wedidnotpursueitfurther.

162SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerumentOursamplebeginsinJanuary1992andendsinMay2013.

Duringthetimeperiodstudied,variousdevelopmentsoccurred(suchasachangeintheexchangerateregimefromcrawlingpegtofreelyfloatingin2001,theadoptionofimplicitinflationtargetingin2002andfull-fledgedinflationtargetingin2005,whichresultedinloweringinflationfrom90%tobetween6%and7%)thatmighthaveledtostructuralchangesintherelationshipamongthemacroeconomicvariablesthatweconsiderintheVARsetting.

Toaccountforthesechanges,weprovidetheimpulseresponseanalysesforthepost-2001financialcrisisera.

Whenthesereponsesareanalyzed,thedecreaseininterestratewasnothigherbutlower(notreported),whichmayindicatethatcapitalflowsmightbegoingtomarketsotherthanmoneyorbondmarkets.

Duringthepost-2001era,inordertoeliminatetheadverseeffectofcapitalflows,theCBRTopenedforeignexchangebuyingauctionsinadditiontoimplementingcreditcontrolsandnewtoolssuchastheROM(Ermioluetal.

2013;Aslaneretal.

2015).

Thus,weincludecentralbankreserves(deflatedwiththelaggedvalueofM2)asanadditionalvariable;thecor-respondingimpulseresponsesarereportedinFigure6.

Includingacentralbankreservesvariablemaylookoddbecausesuchreservesaremostlyunderthedis-cretionoftheCBRT.

Nevertheless,includingthisvariablemaycontrolforcentralbankreservesinthesystemratherthanjustmodelreactiontothecentralbank'sbehavior.

ItcanalsobearguedthatcentralbankreservesmayincreasewiththerequiredreservesofcommercialbanksinforeignexchangedepositsandwiththeROM,whichareheavilytiedtocapitalflowsandgovernmentinstitutions'foreignexchangedeposits.

Figure6revealsthatalowerandstatisticallysignificanteffectonimport,outputandpricesareobservedforthealternativescenariocomparedtothebasescenario.

Thus,inthissense,theresultsarerobust.

However,wecouldnotfindthatexchangeratewasrespondingdifferentlyunderthealternativescenariothanunderthebasescenario.

Thisresultmaybeduetoalowerdegreeoffreedomfromtheshortertimespan,ortotheCBRT'ssuccesswithadditionaltools(suchashigherrequiredreserveratiosonforeign-exchange-denominateddepositsandforeign-currencypurchases)toavoidtheadverseeffectofappreci-atedcurrency.

Thus,wecouldnotobservefurtherappreciatedcurrencyunderthecreditcontrols.

Moreimportantly,evenifinterestratedecreaseswithcapitalflows,thenthedecreasesininterestrateunderthealternativescenarioarenothigherbutlowerthanwhatthebasescenariosuggests.

Theinterestrateresponseisstatisticallysignificantlyhigherthanwhatthebasescenariosug-gestsbetweenthefirstandsixthperiods.

Notethatwithcapitalflows,CBRTreservesincrease.

However,undercreditcontrols,increasesinreservesarehigher.

Thus,CBRTreservesareanoutletforcapitalflows.

TheexercisethatweperformtentativelysupportstheargumentthatcapitalflowsmayhavebeenCreditchannelandcapitalflows163goingtoalternativeoutletssuchascentralbankreservessince2001.

11Overall,wecouldnotfindanyadverseeffectsofcontrollingcreditsforcapitalflowsonexchangerateandinterestrateforthepost-2001era.

Theresultsforimports,outputandprices,however,arerobust.

12Figures2–6reporttheconfidencebandsforthebaselinemodel.

WecomparewhetherourresultswhenthecreditchannelisshutdowndifferfromG:Responseofindustrialproduction00.

20.

40.

60.

81.

00246810121416182022H:Responseofconsumerpriceindex–0.

10–0.

0500.

050.

100.

150.

200246810121416182022D:Responseofcentralbankinternationalreserves–0.

0500.

050.

100.

150.

200.

250.

300246810121416182022E:Responseofcreditstoprivatesector00.

250.

500.

751.

001.

250246810121416182022F:Responseofimport00.

020.

040.

060.

080.

100.

120246810121416182022A:Responseofcapitalflows–0.

200.

20.

40.

60.

81.

01.

20246810121416182022B:Responseofexchangeratebasket–0.

7–0.

6–0.

5–0.

4–0.

3–0.

2–0.

100.

10246810121416182022C:Responseofinterbankinterestrate–50–40–30–20–100100246810121416182022Figure6:ResponsestocapitalflowswithCentralBank'sreservesforthepost-2001crisisera.

Thesolidblacklinesreportthelowerandupperboundsoftheconfidenceintervalforthebasescenario.

Thedashedlinerepresentstheimpulseresponsewhencreditleveliskeptconstant.

11Wealsolookedattheeffectsofcapitalflowsontheequitymarketsandbondmarketsandwecouldnotfindanystatisticallydifferentresultsforthesemarketswhencreditswerecontrolledversusnotcontrolled.

12WealsoperformedtheanalysisreportedinFigure6withthefullsampleandthesampleend-ingbefore2001.

ThebasicresultsofthebenchmarkanalysisarerobustbutwecouldnotobservetheCBRT'sreservesdidnotresponddifferentlyundercreditcontrolversusnocreditcontrol.

164SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerumentthosethebaselinescenarioreveals.

Althoughsuchacomparisoniscommonpracticeintheliterature(see,forexample,Ludvigson,Steindel,andLettau2001;BachmannandSims2012),inFigure7wealsoreportthemedianforthebasescenario(solidline)andtheconfidencebandsforthealternativescenario(dashedlines).

Figure7clearlysuggeststhatwhencreditsareconstrainedcomparedtowhencreditsarenotconstrained,theappreciationofexchangeratewillbehigherafterthesecondperiodinastatisticallysignificantfashionwhencreditsarecontrolled;thedecreaseininterestratewillbehigherbetweenthefirstandninthperiods;theincreaseinimportswillbelowerbetweenthethirdperiodandeleventhperiods;theincreaseinoutputwillbeloweraftertheG:Responseofconsumerpriceindex–0.

6–0.

5–0.

4–0.

3–0.

2–0.

100.

105101520D:Responseofcreditstoprivatesector0.

10.

20.

30.

40.

50.

60.

70.

80.

905101520E:Responseofimport00.

010.

020.

030.

040.

050.

0605101520F:Responseofindustrialproduction0.

050.

100.

150.

200.

250.

300.

350.

400.

4505101520A:Responseofcapitalflows00.

20.

40.

60.

81.

01.

205101520B:Responseofexchangeratebasket–0.

8–0.

7–0.

6–0.

5–0.

4–0.

3–0.

2–0.

105101520C:Responseofinterbankinterestrate–160–140–120–100–80–60–40–20005101520Figure7:ResponsestoCapitalFlowsfortheFullSample:MedianofBenchmarkModelandConfidenceBandsofAlternativeModel.

Thesolidlinesreportthemedianofthebasescenario.

Thedashedlinesrepresentthelowerandupperboundsoftheconfidenceintervalswhencreditleveliskeptconstant.

Creditchannelandcapitalflows165thirteenthperiodandthedecreaseinpriceswillbehigher(priceswilldecreasemore)afterthethirdperiod.

Thus,Figure7revealsstrongersupportforthehypothesisthatshuttingdownthecreditchannelaltersthe(smaller)effectofcapitalflowsoneconomicperformance.

Asnotedabove,weselectalagorderoftwoaccordingtotheBIC,butitispossiblethattheestimatesarebiasedduetolowerparametization.

Toaccountforthispossiblity,weperformtheestimateswithsixlags,assug-gestedbytheFinalPredictionError(FPE)criteria,andstillfindthatthebasicresultsfromFigure2arerobust.

However,eveniflowerandstatisticallysig-nificantexchangerate,interestratesandpricesareobserved,butlowersta-tisticallysignificantindustrialproductionandimportsarenotobservedwhenwecomparethebasescenarioandthealternativescenario,theresultsforthelattermaybeduetoover-paramatization.

Thisanalysisandtheremaininganalysesarenotreportedheretosavespacebutareavailablefromtheauthorsuponrequest.

Theperiodthatweconsiderwasriddledwithvariousexogenousevents,thusweincludeadditivedummiesforthemilitarycoupinFebruary1997,themajorearthquakeinAugust1999,theshiftsinglobalriskappetiteinMarch2003,September2008andOctober2008andthemilitary"e-note"inApril2007.

Ourbasicresultsarestillrobust,butthelevelofsignificancedeterioratesslightlyforexchangerate.

Especiallyduringthe1990s,TurkeywasoneofthemainbeneficiariesofIMFloanstostabilizeitseconomy.

Thus,partofthecapitalflowfiguresincludessuchloans.

Toaccountforthisfact,wealsoperformtheanalogueofFigure2,whichexcludessuchfunds,andfindthattheresultsfromFigure2arestillrobustbutthestatisticalevidenceforexchangerateisweaker.

Turkeyisasmallopeneconomy,withitsexport/revenuemostlydenomi-natedinEurosanditsimport/paymentsmostlydenominatedinUSDollars(seeBerumentandDiner2007).

Thus,weperformtheanalyseswiththe1USD+1Eurobasketexchangerate.

However,capitalflows(andhotmoney)aremeas-uredinUSDollarterms.

WeperformtheimpulseresponsesfortheexchangeratebetweentheTurkishLiraandtheUSDollarratherthanbetweentheTurkishLiravalueofthebasket.

Theresultsarestillrobustbutthestatisticalevidenceforexchangerateisweaker.

Insum,wecanarguethatwhenweconsidervariousalternativesinthissectionfortherelativeeffectofcapitalflowsonmacroeconomicvariableswhencreditsarecontrolledversusnotcontrolled,theestimatesforexchangerate,imports,outputandpricesarerobustandstatisticallysignificant.

Thestatisti-calevidenceforinterestrateisrobustexceptforinFigure6whentheanalysisisperformedforthepost2001era.

166SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerument6ConclusionThispaperassessestheroleofcreditgrowthincontrollingtheadverseeffectsofcapitalflowsoneconomicperformance.

Toaddresstheseeffects,weusedBernanke,GertlerandWatson's(1997)methodology,whichimposesasetofrestrictionsonacreditgrowthscenarioforimpulseresponsefunctionsgatheredfromabaselineVARmodel.

Wegatheredtwodifferentimpulseresponsesfromdifferentcreditgrowthscenarioswhenaone-unitshockwasgiventocapitalflows.

Inthebasescenario,wedidnotimposeanyconstraintsoncreditgrowth,andthusconventionalimpulseresponsesweregatheredfromtheVARspecifica-tion.

Inthealternativescenario,weshutdownthecreditchannel;thatis,thecreditlevelwasequaltoitspre-shocklevelandstayedthere.

Inallthesescenarios,wefoundthatcapitalflowsappreciatedthedomes-ticcurrency,decreasedinterestrateandpricesandincreasedimportandoutputlevels.

Whenwecomparedthebasescenariowiththealternativescenario,wherecreditleveldidnotchange,theappreciationofdomesticcurrencyanddecreasesininterestrateandpriceswerehigher.

However,theincreasesinimportsandoutputwerelower.

Theseresultssuggestthatconstrainingcreditgrowthhelpstheeconomyavoidtheadverseeffectsofcapitalflowsforimportsandoutput.

Suchapolicymayalsohelppreventahighercurrentaccountdeficitbyrestrictingincreasesinimportsandoutput.

Inaddition,althoughshuttingdownthecreditchannelfurtherdecreasesinterestrate,ahigherappreciationindomesticcur-rencymaycauseahigherdecreaseinpricesthanwhatthebasescenariosuggests.

Thisresultreflectsthatconstrainingcreditgrowthmaybeausefulmacropruden-tialpolicytooltoprovidepricestability.

However,ahigherlevelofappreciationmayincreasethedomesticeconomy'svulnerabilityintermsoffinancialstabilitysuchaswhenover-borrowingfromabroadbyforeign-denominatedcurrency.

Inthissense,constrainingcreditgrowthtoeliminatetheadverseeffectsofcapitalflowsmaythusbeonlypartiallyeffective,andshouldlikelybesupplementedwithadditionalpolicies.

Acknowledgments:WewouldliketothankRanaNelsonandthetwoanonymousrefereesfortheirvaluablecomments.

ReferencesAdrian,T.

,andS.

H.

Shin.

2010.

"LiquidityandLeverage.

"JournalofFinancialIntermediation19(3):418–437.

Creditchannelandcapitalflows167Akay,C.

,andErenOcakverdi.

2012.

"AnInterimAssessmentoftheOngoingTurkishMonetaryandMacroPrudentialExperiment.

"ktisatletmeveFinans27(315):77–92.

Akelik,Y.

,E.

Ba,E.

Ermiolu,andArifOduncu.

2013.

"TheTurkishApproachtoCapitalFlowVolatility.

"CBRTWorkingPaper13(06).

Akkaya,Y.

,andS.

R.

Gürkaynak.

2012.

"CurrentAccountDeficit,BudgetBalance,FinancialStabilityandMonetaryPolicy:ReflectionsonaGrippingEpisode.

"ktisatletmeveFinans27(315):93–119.

Alper,C.

E.

,andI.

Salam.

2001.

"TheTransmissionofaSuddenCapitalOutflow:EvidencefromTurkey.

"EasternEuropeanEconomics39(2):29–48.

Alper,K.

,T.

Hülagu,andG.

Kele.

2012.

"AnEmpiricalStudyonLiquidityandBankLending.

"CBRTWorkingPaper12(04).

Alper,K.

,H.

Kara,andM.

Yrükolu.

2013.

"AlternativeToolstoManageCapitalFlowVolatility.

"CBRTWorkingPaper13(31).

Ashcraft,B.

A.

2006.

"NewEvidenceontheLendingChannel.

"JournalofMoney,CreditandBanking38(3):751–775.

Aslan,.

,andH.

L.

Korap.

2007.

"MonetaryTransmissionMechanisminAnOpenEconomyFramework:TheCaseofTurkey.

"Ekonometrivestatistik5:41–66.

Arena,M.

,C.

M.

Reinhart,andF.

F.

Vasquez.

2007.

"TheLendingChannelinEmergingEconomies:AreForeignBanksDifferent"IMFWorkingPaper07(48).

Aslaner,O.

,U.

plak,H.

Kara,andD.

Küüksara.

2015.

"ReserveOptionsMechanism:DoesItWorkAsAnAutomaticStabilizers"CBRTCentralBankReview15:1–18.

Aydin,B.

,andD.

Igan.

2010.

"BankLendinginTurkey:EffectsofMonetaryandFiscalPolicies.

"IMFWorkingPaper10(233).

Aysan,A.

F.

,S.

Fendolu,andM.

Kln.

2014.

"ManagingShort-TermCapitalFlowsinNewCentralBanking:UnconventionalMonetaryPolicyFrameworkinTurkey.

"CBRTWorkingPaper14(03).

Bachmann,R.

,andE.

R.

Sims.

2012.

"ConfidenceandtheTransmissionofGovernmentSpendingShocks.

"JournalofMonetaryEconomics59:235–249.

Bakker,B.

B.

,andA.

M.

Gulde.

2010.

"TheCreditBoomintheEUNewMemberStates:BadLuckorBadPolicies"IMFWorkingPaper10(130).

BankingRegulationandSupervisionAgency.

2006.

FinancialmarketsReport,March–June,Issue.

1–2.

BankingRegulationandSupervisionAgency.

2012.

FinancialmarketsReport,December,Issue.

28.

Barajas,A.

,G.

Dell'Ariccia,andA.

Levchenko.

2009.

CreditBooms:theGood,theBad,andtheUgly,http://www.

nbp.

gov.

pl/Konferencje/NBP_Nov2007/Speakers/Dell_Ariccia.

pdf.

2013.

12.

11.

Ba,E.

2012.

Guvernor'sBa'sPresentationattheConferenceonReserveRequirementsandOtherMacroprudentialPolicies:ExperiencesinEmergingEconomies.

October8,Istanbul.

Ba,E.

,andA.

H.

Kara.

2011.

"FinancialStabilityandMonetaryPolicy.

"ktisatletmeveFinans26(302):9–25.

Ba,E.

,.

zel,and.

Sarkaya.

2007.

"TheMonetaryTransmissionMechanisminTurkey:NewDevelopments.

"CBRTWorkingPaper07(04).

Bernanke,S.

B.

,andS.

A.

Blinder.

1992.

"TheFederalFundsRateandtheChannelsofMonetaryTransmission.

"AmericanEconomicReview82(4):901–921.

Bernanke,S.

B.

,andM.

Gertler.

1995.

"InsidetheBlackBox:TheCreditChannelofMonetaryPolicyTransmission.

"JournalofEconomicPerspectives9(4):27–48.

168SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerumentBernanke,S.

B.

,M.

Gertler,andM.

Watson.

1997.

"SystematicMonetaryPolicyandtheEffectsofOilPriceShocks.

"BrookingsPapersonEconomicActivity1:91–157.

Berument,M.

H.

2007.

"MeasuringMonetaryPolicyforSmallOpenEconomy:Turkey.

"JournalofMacroeconomics29(2):411–430.

Berument,M.

H.

,andN.

Diner.

2007.

"TheEffectsofExchangeRateRiskonEconomicPerformance:TheTurkishExperience.

"AppliedEconomics36(21):2429–2441.

Binici,M.

,andB.

Kksal.

2012.

DeterminantsofCreditBoomsinTurkey,MPRAPaper,38032.

Blanchard,O.

,G.

Dell'Ariccia,andP.

Mauro.

2013.

RethinkingMacroPolicyII:GettingGranular,IMFResearchDepartmentStaffDiscussionNote,SDN/13/03.

Boivin,J.

,T.

M.

Kiley,andS.

F.

Mishkin.

2010.

"HowHasTheMonetaryTransmissionMechanismEvolvedOverTime"NBERWorkingPaperSeries,15879.

Borio,C.

,andH.

Zhu.

2008.

"CapitalRegulation,Risk-TakingandMonetaryPolicy:AMissingLinkintheTransmissionMechanism"BISWorkingPaper,268.

Borio,C.

,R.

McCauley,andP.

McGuire.

2011.

"GlobalCreditandDomesticCreditBooms.

"BISQuarterlyReviewSeptember,43–57.

Brooks,P.

K.

2007.

"TheBankLendingChannelofMonetaryTransmission:DoesitWorkinTurkey"IMFWorkingPaper,07(272).

Calvo,A.

G.

1998.

"CapitalFlowsandCapital-MarketCrises:TheSimpleEconomicsofSuddenStops.

"JournalofAppliedEconomics1(1):35–54.

Cambazolu,B.

,andS.

Güne.

2011.

"MonetaryTransmissionMechanisminTurkeyandArgentina.

"InternationalJournalofEconomicsandFinanceStudies3(2):23–33.

Cecchetti,G.

S.

1999.

"LegalStructure,FinancialStructure,andMonetaryPolicyTransmissionMechanism.

"FRBNYEconomicPolicyReview5(2):9–28.

CentralBankoftheRepublicofTurkey.

2005.

FinancialStabilityReport,August,1.

CentralBankoftheRepublicofTurkey.

2011.

MonetaryandExchanegeRatePolicyfor2012.

CentralBankoftheRepublicofTurkey.

2012a.

MonetaryandExchanegeRatePolicyfor2013.

CentralBankoftheRepublicofTurkey.

2012b.

FinancialStabilityReport,15,November.

CentralBankoftheRepublicofTurkey.

2012c.

ReserveoptionMechanism,CBRTBulletin,28.

CentralBankoftheRepublicofTurkey.

2013.

FinancialStabilityReport,16,May.

Cetorelli,N.

,andL.

Goldberg.

2012.

"BankingGlobalizationandMonetaryTransmission.

"JournalofFinance67(5):1811–1843.

avuolu,T.

2002.

"CreditTransmissionMechanisminTurkey:AnEmpricalInvestigation.

"MiddleEastTechnicalUniversityERCWorkingPapersinEconomics02(03):1–30.

evik,S.

,andK.

Teksz.

2012.

"LostinTransmissionTheEffectivenessofMonetaryPolicyTransmissionChannelsintheGCCCountries.

"IMFWorkingPaper12(191).

iek,M.

2005.

"TheMonetaryTransmissionMechanisminTurkey:AnAnalysisthroughVAR(VectorAutoregression)Approach.

"ktisatletmeveFinansDergisi20(233):82–105.

Demiralp,S.

2008.

"MoneyandtheMonetaryTransmissionMechanisminTurkey.

"ktisatletmeveFinansDergisi23(264):5–20.

Duenwald,K.

C.

,N.

Gueorguiev,andA.

Schaechter.

2005.

"TooMuchofaGoodThingCreditBoomsinTransitionEconomies:TheCasesofBulgaria,Romania,andUkraine.

"IMFWorkingPaper05(128).

Elekda,S.

,andY.

Wu.

2011.

"RapidCreditGrowth:BoonorBoom-Bust"IMFWorkingPaper11(241).

Ermiolu,E.

,A.

Oduncu,andY.

Akelik.

2013.

ReserveOptionMechanisimandExchangeRateVolatility.

(inTurkish),TCMBEkonomiNotlar.

Fuinhas,J.

A.

2008.

"MonetaryTransmissionandBankLendinginPortugal:ASectoralApproach.

"TheIUPJournalofMonetaryEconomics6(1):34–60.

Creditchannelandcapitalflows169Ganiolu,A.

2012.

"FinansalKrizlerinBelirleyicileriOlarakHzlKrediGenilemeleriveCarilemelerA.

"CBRTWorkingPaper12(31).

Gertler,M.

,andS.

Gilchrist.

1994.

"MonetaryPolicy,BusinessCycles,andtheBehaviourofSmallManufacturingFirms.

"TheQuarterlyJournalofEconomics109(2):309–340.

Gourinchas,P.

O.

,O.

R.

Valdes,andO.

Landerretche.

2001.

"LendingBooms:LatinAmericaandtheWorld.

"NBERWorkingPaperSeries,8249.

Gündüz,L.

2001.

"MonetaryTransmissionMechanisminTurkeyandBankLendingChannel.

"MKBJournal18(5):13–30.

Hahm,J.

,S.

F.

Mishkin,S.

H.

Shin,andK.

Shin.

2012.

"MacroprudentialPolicesinOpenEmergingEconomies.

"NBERWorkingPaperSeries,17780.

Hubbard,R.

G.

1994.

"IsThereaCreditChannelforMonetaryPolicy"NBERWorkingPaper,4977.

InstituteofInternationalFinance.

2013.

CapitalFlowsUserGuide.

IIFResearchNote.

.

InstituteofInternationalFinance.

2014.

CapitalFlowstoEmergingMarketEconomiesIIFReserachNoteJanuray30,2014.

InternationalMonetaryFund.

2012.

Turkey:SelectedIssues.

IMFCountryReport,12/39.

InternationalMonetaryFund.

2013.

Turkey:SelectedIssues.

IMFCountryReport,13/364.

Kara,A.

H.

2012.

"MonetaryPolicyinthePost-CrisesPeriod.

"ktisatletmeveFinans27(315):9–36.

Kara,A.

H.

,H.

Küük,S.

T.

Tiryaki,andC.

Yüksel.

2014.

"InSearchofaReasonableCreditGrowthRateforTurkey"CBRTCentralBankReview,14:1–14.

Kashyap,K.

A.

,andC.

J.

Stein.

2000.

"WhatDoaMillionObservationsonBanksSayabouttheTransmissionofMonetaryPolicy"AmericanEconomicReview90(3):407–428.

Kln,M.

,andC.

Tun.

2014.

"IdentificationofMonetaryPolicyShocksinTurkey:AStructuralVARApproach.

"CBRTWorkingPaper,14(23).

Kishan,R.

,andT.

Opiela.

2000.

"BankSize,BankCapital,andtheBankLendingChannel.

"JournalofMoney,Credit,andBanking32(1):121–41.

Lane,R.

P.

,andP.

McQuade.

2013.

"DomesticCreditGrowthandInternationalCapitalFlows.

"EuropeanCentralBankWorkingPaperSeries,July,1566.

Leeper,E.

M.

,C.

A.

Sims,andT.

Zha.

1996.

"Whatdoesmonetarypolicydo"BrookingsPapersonEconomicActivity2:1–63.

Leitemo,K.

,andU.

Sderstrm.

2001.

"SimpleMonetaryPolicyRulesandExchangeRateUncertainty.

"SverigesRiksbankWorkingPaperSeries,122.

Loungani,P.

,andP.

Mauro.

2000.

"CapitalFlightFromRussia.

"IMFPolicyDiscussionPaper,June,6.

Ludvigson,S.

,C.

Steindel,andM.

Lettau.

2001.

MonetaryPolicyTransmissionThroughtheConsumption-WealthChannel,FederalReserveBankofNewYorkEconomicPolicyReview,8(1):May,117–133.

Magud,E.

N.

,M.

C.

Reinhart,andR.

E.

Vesperoni.

2012.

"CapitalInflows,ExchangeRateFlexibility,andCreditBooms.

"IMFWorkingPaper,12(41).

Mendoza,G.

E.

,andE.

M.

Terrones.

2008.

"AnAnatomyofCreditBooms:EvidencefromMacroAggregatesandMicroData.

"NBERWorkingPaperSeries,14049.

Mishkin,S.

F.

1996.

"TheChannelsofMonetaryPolicyTransmission:LessonsforMonetaryPolicy.

"NBERWorkingPaperSeries,5464.

Mishkin,S.

F.

2010.

"MonetaryPolicyFlexibility,RiskManagement,andFinancialDisruptions.

"JournalofAsianEconomics23:242–246.

zatay,F.

2011.

"TheNewMonetaryPolicyoftheCentralBank:TwoTargets-ThreeIntermediateTargets-ThreeTools.

"ktisatletmeveFinans26(302):27–43.

170SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerumentzatay,F.

2012.

"AnExplorationintoNewMonetaryPolicy.

"ktisatletmeveFinans27(315):51–75.

Reinhart,M.

C.

,andA.

G.

Calvo.

2000.

"WhenCapitalInflowsCometoASuddenStop:ConsequencesandPolicyOptions.

"InReformingtheInternationalMonetaryandFinancialSystem,editedbyP.

KenenandA.

Swoboda,175–201.

Washington,DC:InternationalMonetaryFund.

engnül,A.

,andW.

Thorbecke.

2005.

"TheEffectofMonetaryPolicyonBankLendinginTurkey.

"AppliedFinancialEconomics15(13):931–934.

Shin,H.

S.

2012.

"GlobalBankingGlutandLoanRiskPremium.

"IMFEconomicReview60:155–192.

Sims,A.

C.

1992.

"InterpretingtheMacroeconomicTimeSeriesFacts.

"EuropeanEconomicReview36(5):975–1011.

Sims,A.

C.

,andT.

Zha.

2006.

"WerethereregimeswitchesinUSmonetarypolicy"AmericanEconomicReview96:54–81.

Svensson,O.

E.

L.

1998.

"Open-EconomyInflationTargeting.

"NBERWorkingPaperSeries,6545.

Togan,S.

,andM.

H.

Berument.

2011.

"CurrentAccountBalance,CapitalFlowsandCredits.

"BankaclarDergisi78:3–21.

Tornell,A.

,andF.

Westermann.

2002.

"Boom-BustCyclesinMiddle-IncomeCountries:FactsandExplanation.

"IMFStaffPapers49:111–55.

er,M.

2011.

"ObservationonRecentMonetaryPolicyMeasures.

"ktisatletmeveFinans26(302):45–51.

lke,V.

,andM.

H.

Berument.

2014.

EffectivenessofMonetaryPolicyUnderDifferentLevelsofCapitalFlowsforAnEmergingEconomy:Turkey,AppliedEconomicsLetters,forthcoming.

Ylmaz,D.

2008.

GuvernorYlmaz'sPresentationinTrabzon.

September4.

Trabzon.

Ylmaz,D.

2010.

GuvernorYlmaz'sPresentationattheMeetingwiththeGeneralMenagersoftheBanks,December23,Ankara.

CopyrightofB.

E.

JournalofMacroeconomicsisthepropertyofDeGruyteranditscontentmaynotbecopiedoremailedtomultiplesitesorpostedtoalistservwithoutthecopyrightholder'sexpresswrittenpermission.

However,usersmayprint,download,oremailarticlesforindividualuse.

Macroecon.

2016;16(1):145–170ContributionsSerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerument*Creditchannelandcapitalflows:amacroprudentialpolicytoolEvidencefromTurkeyDOI10.

1515/bejm-2015-0052PreviouslypublishedonlineAugust26,2015Abstract:Rapidcreditgrowthinducedbysuddencapitalinflowsmaynegativelyaffectacountry'seconomicperformance,withtheresultingoutflowsturningintoafinancialcrisis.

ThepurposeofthisstudyistodeterminewhethercontrollingthecreditchannelofmonetarypolicycouldbeusedasamacroprudentialtooltosuppresstheeffectsofsuddencapitalinflowsoneconomicperformanceforsmallopeneconomieslikeTurkey.

Inthispaper,usingtheVectorAutoregres-sionmethodologyemployedby(Bernanke,S.

B.

,M.

Gertler,andM.

Watson.

1997.

"SystematicMonetaryPolicyandtheEffectsofOilPriceShocks.

"BrookingsPapersonEconomicActivity1:91–157),weinvestigatewhethershuttingdownthecreditchannelhelpsreducetheeffectsofcapitalinflows.

Indeed,empiricalevi-dencefromTurkeyshowsthatdoingsodecreasestheeffectsofcapitalinflowsonimportsandindustrialproduction,butfurtherdecreasesinterestrateandpricesandfurtherappreciatesthedomesticcurrency.

Therefore,itmaybeprudenttosupportcreditcontrolwithadditionalpolicytoolstopreventafurtherdecreaseininterestrateandpricesandafurtherappreciationofthedomesticcurrency.

Keywords:capitalflows;creditchannel;macroeconomicprudentialpolicy.

JELCodes:E51;E52;E58.

1IntroductionCapitalinflowsasportfolioinvestmentsmayaffectacountry'seconomicper-formanceadverselybecauseoftheexternalfragilityofthedomesticfinancial*Correspondingauthor:M.

HakanBerument,DepartmentofEconomics,BilkentUniversity,06800,Ankara,Turkey,Phone:+903122902342,Fax:+903122662529,e-mail:berument@bilkent.

edu.

trSerdarVarlik:DepartmentofEconomics,HititUniversity,19040,Corum,Turkey146SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerumentmarket,especiallyifachievedthroughthebankingsystemwheninflowedcapitalturnstooutflowedcapital.

Thiseffectoneconomicperformance,frequentlyworkingthroughthecreditchannel,precipitatesfluctuationsinbanks'balancesheetsandmaydecreasecreditquality.

Moreover,currencyappreciationmaydamagepricestabilityandaggravatethecurrentaccountdeficitwithintheframe-workoffinancialstability.

Sincethe2008globalfinancialcrisis,themagnitudeofcapitalflowshasbecomeafactorinthefinancialstabilityofsmallopenecono-mies.

Suchcountries,includingTurkey,havebeguntoadoptvariousmacropru-dentialpolicytoolstopreventtheadverseeffectsofcapitalinflows;controllingbankcreditgrowthisonesuchtool.

Thispapercontributestotheliteratureonthesubjectbyprovidingevidenceforwhetherthecreditchannelcanbeusedasamacroprudentialtooltosuppresstheeffectsofsuddencapitalinflowsoneco-nomicperformanceforsmallopeneconomieslikeTurkey.

Suddencapitalinflowsmaycauseasurplusincreditsupply,looseningcreditstandardsandthusresultinginexcessivecreditgrowth(alsocalledacreditboom).

Thissituationcanthreatenpricestabilityandfinancialstabilitybyenlargingcurrentaccountdeficits,buoyingassetpricesandincreasingdomes-ticdemand.

Suddencapitalinflowsalsoincreasethebankingsector'sforeign-currency-denominatedliabilities(Gourinchas,ValdesandLanderretche2001;ElekdaandWu2011;Magudetal.

2012).

Adversely,aslowdowninshort-termcapitalinflows,suchasiftheeconomyencountersthesuddenstopproblem,maydamageeconomicperformancethroughthecreditchannelandevenresultinafinancialcrisis(Calvo1998;ReinhartandCalvo2000).

Barajas,Dell'Ariccia,andLevchenko(2009)callthisscenarioabadcreditboom,anditoccursbecausecentralbanks,especiallyindevelopingcountries,focusontheexcessivecreditgrowthwithoutplanningfortheproblemsthatcanoccurwhensuddencapitalinflowsstop.

Interestrate,whichisusedasthebasicmonetarypolicytoolbycentralbanksunderaconventionalpolicysettinginsmallopeneconomies,maynotbethebesttooltocontrolcredit.

Forexample,whencentralbanksinthesecoun-triesincreasethepolicyinterestratetocooldowntheeconomyandslowcredits,capitalflowsandcreditsincrease,stimulatingtheeconomy.

Thus,stirringupcapitalinflowsfeedscreditsratherthanconstrainingthem(Hahmetal.

2012).

Thisresultissimilartoanotherdilemma,thatis,whencentralbanksdecreasethepolicyratetodiscouragecapitalinflows.

Alowerinterest-ratepolicymaysparktheassetpricebubble,whichcausescredit-drivenand/orirrationalexuberance(seeMishkin2010).

Lowinterestratesmayalsoresultinexcessiverisktakingintheeconomy,thechannelcalledthe"risk-takingchannelofmonetarypolicy"(BorioandZhu2008,p.

iii).

Alowinterest-ratepolicycancauseanincreaseinthenetinterestratemarginforfinancialinstitutions,whichprovidesmoreprofitCreditchannelandcapitalflows147(AdrianandShin2010),andtherefore,theseinstitutionsmaychoosetoincreasetheleverageratioandsotakeonmoreriskyinvestments,whichincreasesassetprices,loosenscreditsandprecipitatesafinanciallyunstableenvironment.

Thereby,onitsown,interestratemaynotbeaneffectivepolicytooltostabi-lizethefinancialsystem.

Theseemergingdeficienciesinconventionalmonetarypolicysincetheglobalfinancialcrisismaysuggestusingalternativemacropru-dentialpolicytoolsthatcomplementthepolicyratetoolinanunconventionalmonetarypolicyframework.

TheTurkisheconomyprovidesaconvenientenvironmentinwhichtostudytheeffectofcreditcontroloncapitalflowineconomicperformance.

Thecreditchannelisawell-recognizedmethodofusingmonetarypolicytoaffecteco-nomicperformance(seeMishkin1996;Boivin,Kiley,andMishkin2010),andaveryimportantchannelforsmallopeneconomieslikeTurkey.

1Thepurposeofthispaperisnottodocumenttheexistenceorworkingsofthecreditchannelbuttoassesswhethercontrollingthecreditsofthedomesticbankingsystemdecreasestheeffectsofcapitalinflowsonasmallopeneconomy.

Hence,weanalyzetheimpactsofcapitalflowshocksontheeconomicperformanceoftheTurkisheconomythroughthecreditchannelbyusingBernanke,GertlerandWat-son's(1997)VectorAutoregression(VAR)methodology.

TheempiricalevidencegatheredfromtheTurkishcasesuggeststhatshuttingdownthecreditchanneldecreasestheeffectsofcapitalinflowsonimportsandindustrialproduction,butfurtherappreciatesthedomesticcurrencyanddecreasespricesandinterestrates.

Therefore,wesuggestthatcreditcontrolsmightbeonlyoneofasetoftoolsinmacroprudentialpolicytosuppresstheadverseeffectsofcapitalflows.

Turkeyachievedexternalfinancialliberalizationin1989,andsincethen,therelationshipbetweensuddencapitalinflowsandcreditgrowthhasbeengrowingstronger,threateningfinancialstability.

BaandKara(2011)(gover-norandchiefeconomistoftheCentralBankoftheRepublicofTurkey(CBRT),respectively),zatay(2011)(formerCBRTdeputygovernorandformermemberoftheCBRT'sMonetaryPolicyCommission),AkkayaandGürkaynak(2012)(twoacademicians)andKara(2012)statethatsuddencapitalinflowsdramaticallybringabouttwoimportantresultsforTurkey:excessivecreditgrowthandcur-rencyappreciation.

TheCBRTadmitsthatthesetwofactorsasaresultofcapitalinflowsmayresultinpriceinstabilityandfinancialinstability.

TheCBRT(2012a)andAlper,Kara,andYrükolu(2013)indicatethatrapidcurrencyappreciationinducedbycapitalinflowsmayaffectfirms'willingnesstoborrow,leadingtoan1InTurkey,thefinancialsystemischaracterizedbylowfinancialcapitalizationintheequitymarket,lowsecuritizationandlowopportunitiesforrefinancing(suchasforhousingrefinancing).

Forthisreason,thebankingsystemplaysabigroleinthecreditmarket.

148SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerument2See,forexample,BernankeandBlinder(1992),Sims(1992),GertlerandGilchrist(1994),BernankeandGertler(1995),Hubbard(1994),Cecchetti(1999),KishanandOpiela(2000),KashyapandStein(2000),Ashcraft(2006),Fuinhas(2008)andevikandTeksz(2012).

IntheTurkishcase,Gündüz(2001),engnülandThorbecke(2005),Arena,Reinhart,andVasquez(2007),Brooks(2007),Demiralp(2008),Cambazolu,andGüne(2011)andAlper,Hülagu,andKele(2012)arguethatusingthecreditchannelformonetarypolicyoperatesefficientlyinTurkey,butavuolu(2002),iek(2005)andAydinandIgan(2010)donotagree.

excessivelendingappetiteinbanks.

Thus,thebankingsectorincreasescreditstotheprivatesectorexcessively,whichcausesdomesticdemandtogrowfasterthanaggregateincome.

Thisprocessiscalledafinancialacceleratormechanism,andamplifiesbusinesscycles.

Eventually,thecurrentaccountdeficitdramati-callyincreases,inparallelwithcreditboomsandcurrencyappreciation,whichresultsinmacroeconomicinstabilityandevenfinancialcrisis(Ganiolu2012).

Anunforeseeableincreaseincreditgrowthandcurrencyappreciationinducedbyintensivesuddencapitalinflows(alsocalledhotmoney)negativelyaffectthecurrentaccountbalance.

Forexample,in2010,CBRTgovernorYlmazestimatedthata5%increaseincreditgrowthwouldtriggera2.

1%increaseinthecurrentaccountdeficitinTurkeyfortheyear2011(Ylmaz2010).

Therefore,controllingexcessivecreditgrowthmayforestallahighcurrentaccountdeficit.

AkayandOcakverdi(2012)alsosuggestthatcontrollingexcessivecreditgrowthmaysig-nificantlyreduceTurkey'shighcurrentaccountdeficit.

AccordingtoKaraetal.

(2014),anaverageannualcreditgrowthof15%forTurkeywouldbereasonableinthemediumterm.

InthesummaryofitsMonetaryPolicyCommitteeMeetingofJanuary29,2013,theCBRTstatedthat"[m]acroprudentialmeasureswillcontinuetobetaken,should…creditgrowthexpectationsexceed15%foralongperiod.

"Thereissubstantialempiricalresearchanalyzingthevalidityofthecreditchannelformonetarypolicy.

2Therelatedliteratureisenlargedwiththeroleofcapitalflowshocksoncredits,especiallyfordevelopingcountries.

Thesestudiesfocusonthecreditgrowthinducedbycapitalinflows(see,forexample,Gourinchas,ValdesandLanderretche2001;TornellandWestermann2002;Duenwaldetal.

2005).

Thisliteraturehasbeengrowingrapidlysincetheglobalfinancialcrisis:MendozaandTerrones(2008),BakkerandGulde(2010),Borioetal.

(2011),Shin(2012),CetorelliandGoldberg(2012)andLaneandMcQuade(2013)allpointoutthatcapitalflowsandinternationalliquiditydeterminefluc-tuationsincredits(boomandbusts)throughthecreditchannelandthusdeter-mineeconomicperformance.

Allauthorsunderlinetheadverseeffectsofcreditgrowthinducedbysuddencapitalinflows,andtheTurkishcasehasplentyofevidenceshowingthisrelationship(seeAlperandSalam2001;AslanandKorap2007;ToganandBerument2011;BiniciandKksal2012).

Creditchannelandcapitalflows149Thispaperisorganizedinsixsections.

InSectionII,webrieflyexplaintherelationshipamongcapitalflows,creditsandthecurrentaccountbalanceinTurkey.

InSectionIII,weoutlinethemethodologyemployedtoassesstheeffectofshuttingdownthecreditchannel.

SectionIVpresentstheempiricalevidenceunderalternativescenarios.

SectionVprovidesasetofrobustnessanalysesandSectionVIconcludesthepaper.

2TherelationshipbetweencapitalflowsandcreditsinTurkey:ashortstoryThebankingsectorplaysanimportantroleinthefinancialmarket,especiallyfordevelopingcountriessuchasTurkey,duetothesector'sbiggershareinthewholefinancialsystemcomparedtodevelopedcountries;banksnotonlydeterminefinancialdeepeningandbutalsotheefficiencyofmonetarypolicy(seeCecchetti1999).

IntheTurkishcase,thebankingsector'sshareofthebalancesheetinthefinancialsystemwas91.

5%in2004and87.

6%in2012(CBRT2005,2013).

Althoughthesharewaslowerin2012,thebankingsectorremainshighlydominantoverall;whilethepercentageassetshareofthebankingsectorintheGDPwas71.

2%in2004,thisratioreached98%in2012(BankingRegulationandSupervisionAgency2006,2012).

Therefore,thecreditchannel,especiallythebanklendingchannel,isimportantfortheTurkisheconomy.

Sincetheintroductionofstructuralreformsin2001,thecreditchannelhasbeenworkingmoreefficientlythanothermonetarypolicytransmissionmechanisms(Ba,zel,andSarkaya2007).

Toassesstheimportanceofcreditgrowth,wefirstprovideasetofdescrip-tivestatistics(Table1).

Thetableshowsahighcorrelationbetweencreditsandeconomicperformance,whichsuggeststheimportanceofthecreditchannel.

Thecorrelationcoefficientsbetweencreditsandimports,betweencreditsandindus-trialproductionandbetweencreditsandconsumerpriceindexaremorethan0.

85.

Furthermore,thecorrelationcoefficientbetweencreditsandcapitalflowsis0.

66,whichshowsthecloserelationshipbetweencreditsandcapitalflows.

Figure1showstherelationshipbetweencreditsandcapitalflows,andbetweencreditsandthecurrentaccountdeficit.

Whilerealcreditgrowthandcapitalandfinancialaccountsmovetogether,realcreditgrowthandthecurrentaccountdeficitmoveintheoppositedirectionfromeachother.

Todetectthefundamentalrelation-shipbetweencreditsandcapitalinflowsinTurkey,wefocusontheyearssinceexter-nalfinancialliberalization(1989onward).

Respectively,increasesanddecreasesinrealcreditgrowthhavebeenaccompaniedbycapitalinflowsandoutflowssincethe1990s.

AsevidentinFigure1,duringthe1994financialcrisis,whileincrease150SerdarVarlikandM.

HakanBerumentinrealcreditfirstslowedandthendecreaseddependingoncapitaloutflows,thecurrentaccountdeficitalsodecreasedandthussodidthecurrentaccountsurplus.

Similarly,the1998AsianfinancialcrisisinducedcapitaloutflowsfromTurkeybecauseofdecreasedglobalriskappetite.

Thesecapitaloutflowsledtodecreasesinrealcreditgrowthandcurrentaccountdeficits.

Thisstoryamongcapitalflows,creditsandcurrentaccountshasrepeatedlyplayedoutinTurkey,especiallysince1999.

Whencapitalinflowsinthepre-financial-crisisperiodturnedintocapitalout-flowsduringtheNovember2000andtheFebruary2001financialcrises,realcreditgrowthdramaticallycontracted,andcorrespondingly,acurrentaccountsurplusemerged.

InApril2001,thegovernmentannouncedtheTransitiontoaStrongEconomyProgram,whoseaimsincludedbankingsectorsoundness,pricestabil-ityandloweredfiscaldominance;an(implicit)inflationtargetingstrategybeganinJanuary2002.