assoubuntu9.04

ubuntu9.04 时间:2021-03-28 阅读:()

InnovationsSystSoftwEng(2010)6:219–231DOI10.

1007/s11334-010-0129-9ORIGINALPAPERFormallyverifyinghuman–automationinteractionaspartofasystemmodel:limitationsandtradeoffsMatthewL.

Bolton·EllenJ.

BassReceived:8March2010/Accepted:25March2010/Publishedonline:9April2010TheAuthor(s)2010.

ThisarticleispublishedwithopenaccessatSpringerlink.

comAbstractBoththehumanfactorsengineering(HFE)andformalmethodscommunitiesareconcernedwithimprovingthedesignofsafety-criticalsystems.

Thisworkdiscussesamodelingeffortthatleveragedmethodsfrombotheldstoperformformalvericationofhuman–automationinter-actionwithaprogrammabledevice.

Thiseffortutilizesasystemarchitecturecomposedofindependentmodelsofthehumanmission,humantaskbehavior,human-deviceinter-face,deviceautomation,andoperationalenvironment.

ThegoalsofthisarchitectureweretoallowHFEpractitionerstoperformformalvericationsofrealisticsystemsthatdependonhuman–automationinteractioninareasonableamountoftimeusingrepresentativemodels,intuitivemodelingcon-structs,anddecoupledmodelsofsystemcomponentsthatcouldbeeasilychangedtosupportmultipleanalyses.

Thisframeworkwasinstantiatedusingapatientcontrolledanal-gesiapumpinatwophasedprocesswheremodelsineachphasewereveriedusingacommonsetofspecications.

Therstphasefocusedonthemission,human-deviceinterface,anddeviceautomation;andincludedasimple,unconstrainedhumantaskbehaviormodel.

Thesecondphasereplacedtheunconstrainedtaskmodelwithonerepresentingnormativepumpprogrammingbehavior.

Becausemodelsproducedintherstphaseweretoolargeforthemodelcheckertoverify,anumberofmodelrevisionswereundertakenthataffectedthegoalsoftheeffort.

Whiletheuseofhumantaskbehaviormodelsinthesecondphasehelpedmitigatemodelcomplex-ity,vericationtimeincreased.

AdditionalmodelingtoolsM.

L.

Bolton(B)·E.

J.

BassDepartmentofSystemsandInformationEngineering,UniversityofVirginia,151Engineer'sWay,Charlottesville,VA,USAe-mail:mlb4b@virginia.

eduE.

J.

Basse-mail:ejb4n@virginia.

eduandtechnologicaldevelopmentsarenecessaryformodelcheckingtobecomeamoreusabletechniqueforHFE.

KeywordsHuman–automationinteraction·Taskanalysis·Formalmethods·Modelchecking·Safetycriticalsystems·PCApump1IntroductionBothhumanfactorsengineering(HFE)andformalmethodsareconcernedwiththeengineeringofrobustsystemsthatwillnotfailunderrealisticoperatingconditions.

Thetraditionaluseofformalmethodshasbeentoevaluateasystem'sauto-mationunderdifferentoperatingand/orenvironmentalcon-ditions.

However,humanoperatorscontrolanumberofsafetycriticalsystemsandcontributetounforeseenproblems.

Forexample,humanbehaviorhascontributedtobetween44,000and98,000deathsnationwideeveryyearinmedicalpractice[18],74%ofallgeneralaviationaccidents[19],atleasttwo-thirdsofcommercialaviationaccidents[28],andanumberofhighproledisasterssuchastheincidentsatThreeMileIslandandChernobyl[22].

HFEfocusesonunderstandinghumanbehaviorandapplyingthisknowledgetothedesignofhuman–automationinteraction:makingsystemseasiertousewhilereducingerrorsand/orallowingrecoveryfromthem[25,29].

ByleveragingtheknowledgeofbothHFEandformalmethods,researchershaveidentiedthecognitiveprecon-ditionsformodeconfusionandautomationsurprise[7,10,16,23];automaticallygenerateduserinterfacespecications,emergencyprocedures,andrecoverysequences[13,14];andidentiedhumanbehaviorsequences(normativeorerrone-ous)thatcontributetosystemfailures[8,12].

123220M.

L.

Bolton,E.

J.

BassWhileallofthisworkhasproducedusefulresults,themodelshavenotincludedallofthecomponentsnecessarytoanalyzehuman–automationinteraction.

ForHFEanalysesofhuman–automationinteraction,theminimalsetofcom-ponentsarethegoalsandproceduresofthehumanopera-tor;theautomatedsystemanditshumaninterface;andtheconstraintsimposedbytheoperationalenvironment.

Cogni-tiveworkanalysisisconcernedwithidentifyingconstraintsintheoperationalenvironmentthatshapethemissiongoalsofthehumanoperator[27];cognitivetaskanalysisiscon-cernedwithdescribinghowhumanoperatorsnormativelyanddescriptivelyperformgoalorientedtaskswheninteract-ingwithanautomatedsystem[17,24];andmodelingframe-workssuchas[11]seektonddiscrepanciesbetweenhumanmentalmodels,human-deviceinterfaces(HDIs),anddeviceautomation.

Inthiscontext,problemsrelatedtohuman–automationinteractionmaybeinuencedbythehumanoperator'smission,thehumanoperator'staskbehavior,theoperationalenvironment,theHDI,thedevice'sautomation,andtheirinterrelationships.

Wearedevelopingmethodsandtoolstoallowhumanfactorsengineerstoexploittheirexistinghumantaskmodelingconstructswiththepowerfulvericationcapabil-itiesofformalmethodsinordertoidentifypotentialprob-lemswithhuman–automationinteractioninsafetycriticalsystemsthatmayberelatedtohumantaskbehavior,theautomateddevice,theoperationalenvironment,ortheirinter-action.

Tothisend,wearedevelopingacomputationalframe-work(Fig.

1)fortheformalmodelingofhuman-automationinteraction.

Thisframeworkutilizesconcurrentmodelsofhumanoperatortaskbehavior,humanmission(thegoalstheoperatorwishestoachieveusingthesystem),deviceauto-mation,andtheoperationalenvironmentwhicharecom-posedtogethertoformalargersystemmodel.

Inter-modelinteractionisrepresentedbyvariablessharedbetweenmod-els.

Environmentvariablescommunicateinformationaboutthestateoftheenvironmenttothedeviceautomation,mis-sion,andhumantaskmodels.

Missionvariablescommuni-catethemissiongoalstothehumantaskmodel.

InterfacevariablesconveyinformationaboutthestateoftheHDI(dis-playedinformation,thestateofinputwidgets,etc.

)tothehumantaskmodel.

ThehumantaskmodelindicateswhenandwhatactionsahumanoperatorwouldperformontheHDI.

TheHDIcommunicatesitscurrentstatetothedeviceauto-mationviatheinterfacevariables.

TheHDIreceivesinfor-mationaboutthestateofthedeviceautomationmodelviatheautomationstatevariables.

Forbroaderapplicability,theanalysisframeworkmustsupportmodelingconstructsintuitivetothehumanfac-torsengineerinordertoallowhimtoeffectivelymodelhumanmissions,humantasks,andHDIs.

Becauseanengi-neermaywishtorerunvericationsusingdifferentmissions,taskmodels,HDIs,environments,orautomationbehaviors,thesecomponentsshouldremaindecoupled(asisthecaseinFig.

1).

Finally,themodelingtechniquemustbecapableofrepresentingthetargetsystemswithenoughdelitytoallowtheengineertoperformthedesiredverication,anddosoinareasonableamountoftime(thiscouldmeanseveralhoursforasmallproject,orseveraldaysforamorecomplicatedone).

ThispaperdescribesaninstantiationofthisframeworkusingamodelofaBaxterIpumpPainManagementSystem[2],apatientcontrolledanalgesia(PCA)pumpthatadminis-terspainmedicationinaccordancewithconstraintsdenedbyahealthcaretechnician(describedinSect.

2.

1).

Modelsweredevelopedintwophases.

TherstphaseinvolvedtheconstructionanddebuggingoftheHDI,deviceautomation,andhumanmissionmodels(anenvironmentalmodelwasnotSystemModelHumanTaskModelDeviceAutomationModelHuman-DeviceInterfaceModelMissionModelEnvironmentModelMissionVariablesHumanActionVariablesInterfaceVariablesInterfaceVariablesAutomationStateVariablesEnvironmentVariablesFig.

1Frameworkfortheformalmodelingofhuman–automationinteraction.

Arrowsbetweenmodelsrepresentvariablesthataresharedbetweenmodels.

Thedirectionofthearrowindicateswhethertherep-resentedvariablesaretreatedasinputsoroutput.

Ifthearrowissourcedfromamodel,therepresentedvariablesareoutputsofthatmodel.

Ifthearrowterminatesatamodel,therepresentedvariablesareinputstothatmodel123Formallyverifyinghuman–automationinteraction221includedbecauseofthegeneralstabilityoftheenvironmentinwhichanactualpumpoperates)withanunconstrainedhumantaskmodelservingasaplaceholderforamorereal-istichumantaskmodel.

Thesecondextendedthemodelpro-ducedinPhase1witharealisticmodelofthehumantask,completingtheframework.

Eventhoughthetargetdeviceinthismodelingeffortwasseeminglysimple,thesystemmodelthatwasinitiallydevel-opedinPhase1(Phase1a)wastoodifcultforthemodelcheckertoprocessquicklyandtoocomplexforittoverify.

Thusanumberofrevisionswereundertaken[3].

InPhase1bareducedandabstractedmodeloftheBaxterIpumpwasproducedwhich,whilecapableofbeingusedinsomever-ications,didsoattheexpenseoflimitingthenumberofgoalsrepresentedinthehumanmissionmodel.

ThisPhase1bmodellimitedtheusefulnessofincorporatinghumantaskbehaviorinPhase2.

Thus,inPhase1c,thesystemmodelwasreducedtoencompasstheprogrammingprocedureforamuchsimplerPCApump.

InPhase2,theincorporationofthemorerealistichumantaskbehavioractuallyresultedinareductionofthetotalsystemmodel'scomplexity,butdidsoattheexpenseofanincreaseinvericationtime.

Thispaperdiscussesthesemodelingphases,thevericationresultspro-ducedinthem,andtheirassociatedcompromisesinrelationtothegoalsofthemodelingarchitecture.

Theseareusedtodrawconclusionsaboutthefeasibilityofusingformalmeth-odstoinformhuman–automationinteraction.

2Methods2.

1ThetargetsystemTheBaxterIpumpisanautomatedmachinethatcontrolsdeliveryofsedative,analgesic,andanestheticmedicationsolutions[2].

Solutiondeliveryviaintravenous,subcutane-ous,andepiduralroutesissupported.

Medicationsolutionsaretypicallystoredinbagslockedinacompartmentonthebackofthepump.

Pumpbehaviorisdictatedbyinternalautomation,whichcandependonhowthepumpisprogrammedbyahumanoperator.

PumpprogrammingisaccomplishedviaitsHDI(Fig.

2)whichcontainsadynamicLCDdisplay,asecu-ritykeylock,andeightbuttons.

Whenprogrammingthepump,theoperatorisabletospecifyallofthefollowing:whethertouseperiodicorcontinuousdosesofmedications(i.

e.

,themodewhichcanbePCA,Basal+PCA,orContinu-ous),whethertouseprescriptioninformationpreviouslypro-grammedintothepump,theuidvolumecontainedinthemedicationbag,theunitsofmeasureusedfordosage(ml,mg,org),whetherornottoadministerabolus(aninitialdoseofmedication),dosageamounts,dosageowrates(foreitherbasalorcontinuousratesasdeterminedbythemode),StartStopEnterOn/OffClearCLCDDisplayInterfaceMessageDisplayedValueCursorSecurityKeyLeftButtonUp(Scroll)ButtonRightButtonClearButtonStartButtonStopButtonEnterButtonOn/OffButtonFig.

2AsimpliedrepresentationoftheBaxterIpump'shuman-deviceinterface.

Notethattheactualpumpcontainsadditionalcontrolsandinformationconveyancesthedelaytimebetweendosages,and1hlimitsontheamountofdeliveredmedication.

Duringprogramming,thesecuritykeyisusedtolockandunlockthecompartmentcontainingthemedicationsolution.

Theunlockingandlockingprocessisalsousedasasecuritymeasuretoensurethatanauthorizedpersonisprogrammingthepump.

Thestartandstopbuttonsareusedtostartandstopthedeliveryofmedicationatspecictimesduringpro-gramming.

Theon–offbuttonisusedtoturnthedeviceonandoff.

TheLCDdisplaysupportspumpoperationoptions.

Whentheoperatorchoosesbetweentwoormoreoptions,theinter-facemessageindicateswhatisbeingchosen,andtheinitialordefaultoptionisdisplayed.

Pressingtheupbuttonallowstheprogrammertoscrollthroughtheavailableoptions.

Whenanumericalvalueisrequired,theinterfacemessageconveysitsnameandthedisplayedvalueispresentedwiththecursorunderoneofthevalue'sdigits.

Theprogrammercanmovethepositionofthecursorbypressingtheleftandrightbuttons.

Heorshecanpresstheupbuttontoscrollthroughthedifferentdigitvaluesavailableatthatcursorposition.

Theclearbuttonsetsthedisplayedvaluetozero.

Theenterbuttonisusedtoconrmvaluesandtreatmentoptions.

Asidefromtheadministrationoftreatment,thepump'sautomationsupportsdynamiccheckingandrestrictionofoperatorenteredvalues.

Thus,inadditiontohavinghardlim-itsonvalueranges,theextremacanchangedynamicallyinresponsetootheruserspeciedvalues.

2.

2ApparatusAllformalmodelswereconstructedusingtheSymbolicAnalysisLaboratory(SAL)language[9]becauseofitsasso-ciatedanalysisanddebuggingtools,anditssupportforboththeasynchronousandsynchronouscompositionofdifferent123222M.

L.

Bolton,E.

J.

Bassmodels(modulesusingSAL'sinternalsemantics).

ThetaskmodelrepresentationsdescribednextweretranslatedintotheSALlanguageasasinglemoduleusingacustom-builtjavaprogram[5].

AllvericationsweredoneusingSAL-SMC3.

0,theSALsymbolicmodelchecker.

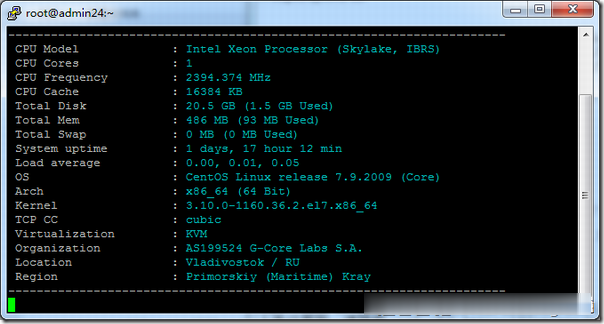

1Vericationswereconductedona3.

0GHzdual-coreIntelXeonprocessorwith16GBofRAMrunningtheUbuntu9.

04desktop.

Humantaskmodelswerecreatedusinganintermediarylanguagecalledenhancedoperatorfunctionmodel(EOFM)[4],anXML-based,generichumantaskmodelinglan-guagebasedontheoperatorfunctionmodel(OFM)[21,26].

EOFMsarehierarchicalandheterarchicalrepresentationsofgoalormissiondrivenactivitiesthatdecomposeintolowerlevelactivities,andnally,atomicactions—whereactionscanrepresentanyobservable,cognitive,orperceptualhumanbehavior.

EOFMsexpresstaskknowledgebyexplicitlyspec-ifyingtheconditionsunderwhichhumanoperatoractivi-tiescanbeundertaken:whatmustbetruebeforetheycanexecute(preconditions),whentheycanrepeat(repeatcon-ditions),andwhentheyhavecompleted(completioncondi-tions).

Anyactivitycandecomposeintooneormoreotheractivitiesoroneormoreactions.

Adecompositionoperatorspeciesthetemporalrelationshipsbetweenandthecardi-nalityofthedecomposedactivitiesoractions(whentheycanexecuterelativetoeachotherandhowmanycanexecute).

EOFMscanberepresentedvisuallyasatree-likegraphstructure(examplescanbeseeninFigs.

3,4,5,6,7).

Intheserepresentations,actionsarerepresentedasrect-anglesandactivitiesarerepresentedasroundedrectan-gles.

Anactivity'sdecompositionispresentedasanarrow,labeledwiththedecompositionoperator,extendingbelowitthatpointstoalargeroundedrectanglecontainingthedecomposedactivitiesoractions.

Inthiswork,threedecompositionoperatorsareused:(1)ord(allactivitiesoractionsinthedecompositionmustexecuteintheordertheyappear);(2)or_seq(oneormoreoftheactivitiesoractionsinthedecompositionmustexecute);and(3)xor(exactlyoneactivityoractioninthedecompositionmustexecute).

Conditionsonactivitiesarerepresentedasshapesorarrows(annotatedwiththeconditionlogic)con-nectedtotheactivitythattheyconstrain.

Theform,posi-tion,andcoloroftheshapearedeterminedbythetypeofcondition.

Apreconditionispresentedasayellow,downward-pointingtriangleconnectedtotheleftsideoftheactivity.

Acompletionconditionisrepresentedbyamagenta,upward-pointingtriangleconnectedtotherightsideoftheactivity.

Arepeatconditionisdepictedasanarrowrecur-sivelypointingtothetopoftheactivity.

Moredetailscanbefoundin[4].

1SomemodeldebuggingwasalsoconductedusingSAL'sboundedmodelchecker.

2.

3VericationspecicationTwospecicationswereemployedineachofthemodelingphases:bothwerewritteninlineartemporallogicandeval-uatedusingSAL–SMC.

Therst(Eq.

1),usedformodeldebugging,veriesthatavalidprescriptioncouldbepro-grammedintothepump:GiInterfacemessage=TreatmentAdministering∧iMode=iPrescribedMode∧lFluidVolume=iPrescribedFluidVolume∧lPCADose=iPrescribedPCADose∧lDelay=iPrescribedDelay∧lBasalRate=iPrescribedBasalRate∧l1HourLimit=iPrescribed1HourLimit∧lBolus=iPrescribedBolus∧lContinuousRate=iPrescribedContinuousRate(1)Here,ifthemodelisabletoenterastateindicatingthattreatmentisadministering(iInterfaceMessage=Treat-mentAdministering)withtheentered(orprogrammed)prescriptionvalues(iMode,lFluidVolume,…,lContinuous-Rate)matchingtheprescriptionvaluesgeneratedbythemissionmodel(variableswiththeiPrescribedprex),acounterexamplewouldbeproducedillustratinghowthatpre-scriptionwasprogrammed.

Variableswithaniprexindicatethatthevariableisaninputtothehumantaskmodel.

Vari-ableswithanlprexindicatethatthevariableislocaltoagivenmodel.

Thesecondspecication(Eq.

2)representedasafetyprop-ertythatwasexpectedtoverifytotrue,thusallowingthemodelcheckertotraversetheentirestatespaceofeachphase'smodel.

BecausesuchavericationallowsSALtoreportthesizeofamodel'sstatespace,vericationsusingthisspecicationwouldprovidesomemeansofcomparingthecomplexityofthemodelsproducedineachphase.

GiInterfaceMessage=TreatmentAdministering∧iMode=Continuous∧lDelay=0(2)Here,thespecicationisassertingthatthemodelshouldneverenterastatewheretreatmentisadministeringinthePCAorBasal+PCAmodes(iMode=Continuous)whenthereisnodelaybetweendoses.

2Thus,ifEq.

(2)veriestotrue,thepumpwillneverallowaprogrammertoenterprescriptionsthatwouldallowpatientstocontinuouslyadministerPCAdosestothemselves[2].

2AdelaycanonlybeensetwhenthePCAorBasal+PCAmodeshavebeenselectedbythehumanoperator.

TherearenodelaysbetweendoseswhenthepumpisintheContinuousmode.

123Formallyverifyinghuman–automationinteraction2233Phase1a:arepresentativemodeloftheIpump3.

1ModeldescriptionAninitialmodelwascreatedtoconformtothearchitecturalanddesignphilosophyrepresentedinFig.

2:themissionwasrepresentedasasetofviableprescriptionsoptions;themis-sion,humanoperator,human-deviceinterface,anddeviceautomationweremodeledindependentlyofeachother;andthebehavioroftheautomatedsystemandHDImodelswasdesignedtoaccuratelyreectthebehaviorofthesesystemsasdescribedintheuser'smanual[2]andobservedthroughdirectinteractionwiththedevice.

Anunconstrainedhumanoperatorwasconstructedthatcouldissueanyvalidhumanactiontothehuman-deviceinterfacemodelatanygiventime.

BecausethePCApumpgenerallyoperatesinacon-trolledenvironment,awayfromtemperatureandhumidityconditionsthatmightaffecttheperformanceofthepump'sautomation,noenvironmentalmodelwasincluded.

Finally,becausedocumentationrelatedtotheinternalworkingsofthepumpwaslimited,thesystemautomationmodelwasrestrictedtothatassociatedwiththepumpprogrammingpro-cedure:behaviorthatcouldbegleanedfromtheoperator'smanual[2],correspondenceswithhospitalstaff,anddirectinteractionwiththepump.

3.

2ModelcoordinationModelinfrastructurewasrequiredtoensurethathumanoper-atoractionswereproperlyrecognizedbytheHDImodel.

Inanidealmodelingenvironment,humanactionbehaviororig-inatingfromthehumanoperatormodelcouldhavebothanasynchronousandsynchronousrelationshipwiththeHDImodel.

SynchronousbehaviorwouldallowtheHDImodeltoreacttouseractionsinthesametransitioninwhichtheywereissued/performedbythehumanoperatormodel.

How-ever,boththehumanoperatorandHDImodelsoperateinde-pendentlyofeachother,andmayhavestatetransitionsthataredependentoninternalorexternalconditionsthatarenotdirectlyrelatedtothestateoftheothermodel.

Thissuggestsanasynchronousrelationship.

SALonlyallowsmodelstobecomposedwitheachotherasynchronouslyorsynchronously(butnotboth).

Thus,itwasnecessarytoadaptthemodelstosupportfeaturesassociatedwiththeunusedcomposition.

AsynchronouscompositionwasusedtocomposethehumanoperatorandHDImodels.

ThisnecessitatedsomeadditionalinfrastructuretopreventthehumanoperatormodelfromissuinguserinputsbeforetheHDImodelwasreadytointerpretthemandtopreventthehumanoperatormodelfromterminatingagiveninputbeforetheinterfacecouldrespondtoit.

Thiswasaccomplishedthroughtheaddi-tionoftwoBooleanvariables:oneindicatingthatinputhadbeensubmitted(henceforthcalledSubmitted)andavariableindicatingtheinterfacewasreadytoreceiveactions(hence-forthcalledReady).

Thiscoordinationoccurredasfollows:–IfReadyistrueandSubmittedisfalse,thehumanoperatormodulesetsoneormoreofthehumanactionvariablestoanewinputvalueandsetsSubmittedtotrue.

–IfReadyandSubmittedaretrue,thehuman-deviceinter-facemodulerespondstothevaluesofthehumanactionvariablesandsetsReadytofalse.

–IfReadyisnottrueandSubmittedistrue,thehumanoper-atormodulesetsSubmittedtofalse.

–IfReadyandSubmittedarebothfalseandtheautomatedsystemisreadyforadditionalhumanoperatorinput,thehuman-deviceinterfacemodulesetsReadytotrue.

3.

3VericationresultsAttemptstoverifythismodelusingthespecicationsinEqs.

1and2resultedintwoproblemsrelatedtothefeasibilityandusefulnessofthevericationprocedure.

First,theSAL–SMCprocedurefortranslatingtheSALcodeintoabinarydecisiondiagram(BDD)tookexcessivelylong(morethan24h),atimeframeimpracticalformodeldebugging.

Second,thevericationprocesswhichfollowedtheconstructionoftheBDDeventuallyranoutofmemory,thusnotreturningavericationresult.

4Phase1b:areducedBaxterIpumpmodelAsaresultofthefailedvericationofthemodelproducedinPhase1a,significantrevisionswererequiredtomakethemodelmoretractable.

Thesearediscussedbelow.

4.

1RepresentationofnumericalvaluesToreducethetimeneededtoconverttheSAL-codemodeltoaBDD,anumberofmodicationsweremadetothemodelfromPhase1abyrepresentingmodelconstructsinwaysmorereadilyprocessedbythemodelchecker.

Assuch,themod-icationsdiscussedheredidnotultimatelymaketheBDDrepresentationofthemodelsmaller,butmerelyexpediteditsconstruction.

4.

1.

1RedundantrepresentationofvaluesTwodifferentrepresentationsofthevaluesprogrammedintothepumpbytheoperatorwereusedintheHDIanddeviceautomationmodels.

BecausetheHDIrequiredthehumanoperatortoentervaluesbyscrollingthroughtheavailablevaluesforindividualdigits,anarrayofintegerdigitswasappropriatefortheHDImodel.

However,becausethesystem123224M.

L.

Bolton,E.

J.

Bassautomationwasconcernedwithdynamicallycheckinglimitsandusingenteredvaluestocomputeothervalues,anumer-icalrepresentationoftheactualvaluewasmoreconvenientfortheautomatedsystemmodel.

ThisredundancyburdenedtheBDDtranslator.

Thiswasremediedbyeliminatingthedigitarrayrepresentationsandusingfunctionstoenableactionsfromthehumantaskmodeltoincrementallychangeindividualdigitswithinavalue.

4.

1.

2RealnumbersandintegersInthemodelproducedinPhase1a,allnumericalvalueswererepresentedasrealvalueswithrestrictedranges.

Thiswasdonebecausemostuserspeciedvalueswereeitherinte-gersoroatingpointnumbers(precisetoasingledecimalpoint).

Nodataabstractionswereinitiallyconsideredbecausethenatureofthehumantask(modeledinPhase2)requiredmanipulationofvalues'individualdigits.

However,repre-sentingvaluesthiswayprovedespeciallychallengingfortheBDDtranslator.

Thus,allvaluesweremodiedsothattheycouldberepresentedasrestrictedrangeintegers.

Forintegervariablesrepresentingoatingpointnumbers,thismeantthatthemodelvaluewastentimesthevalueitrepresented.

Thisrepresentationallowedthevaluestostillbemanipulatedattheindividualdigitlevel,whilemakingthemmorereadilyinterpretablebytheBDDtranslator.

4.

1.

3VariablerangesInthePhase1amodel,theupperboundontherangeofallvalue-basedvariableswassettothetheoreticalmaximumofanyvaluethatcouldbeprogrammedintothepump:99,999.

3However,toreducetheamountofworkrequiredfortheBDDconversion,therangeofeachnumericallyvaluedvariablewasgivenaspecicupperboundthatcorrespondedtothemaximumvalueitcouldactuallyassumeinthedevice.

4.

2ModelreductionToreducethesizeofthemodel,avarietyofelementswereremoved.

InallcasesthesereductionsweremeanttoreducethenumberofstatevariablesintheHDIordeviceautoma-tionmodels(slicing),orreducetherangeofvaluesavariablecouldassume(dataabstraction).

Unfortunately,eachofthesereductionsalsoaffectedwhathumantaskscouldultimatelybemodeledandthusveriedinsubsequentmodeliterations.

Allofthefollowingreductionswereundertaken:–InthePhase1amodel,themissionmodelcouldgener-ateaprescriptionfromtheentireavailablerangeofvalidprescriptions.

Thiswaschangedsothatfewerprescription3Alllowerboundsweresetto0.

optionsweregeneratedinPhase1b'smissionmodel:thatofprogrammingaprescriptionwithacontinuousdosagewithtwooptionsforbolusdelivery(0.

0and1.

0ml)andtwocontinuousowrateoptions(1.

0and9.

0ml/h).

Whilethissignificantlyreducedthenumberofmodelstates,italsoreducedthenumberofprescriptionsthatcouldbeusedinvericationprocedures.

–InthePhase1amodel,theHDImodelwouldallowtheoperatortoselectwhatunitstousewhenenteringprescrip-tions(ml,mg,org).

OnlythemlunitoptionwasincludedinthePhase1bmodel.

Thisreducedthenumberofinter-facemessagesinthemodel,allowedfortheremovalofseveralvariables(thoserelatedtotheunitoptionselection,andsolutionconcentrationspecication),andreducedtherangesrequiredforseveralnumericalvaluesrelatedtotheprescription.

Thiseliminatedtheoptionofincludingunitselectionandconcentrationspecicationtaskbehaviorsinthemodel.

–InthePhase1amodel,boththeHDIanddeviceautomationmodelsencompassedbehaviorrelatedtothedeliveryofmedicationsolutionduringtheprimingandbolusadmin-istrationprocedures.

Duringpriming,theHDIallowstheoperatortorepeatedlyinstructthepumptoprimeuntilallairhasbeenpushedoutoftheconnectedtubing.

Duringbolusadministration,theHDIallowstheoperatortotermi-natebolusinfusionbypressingthestopbuttontwice.

ThisfunctionalitywasremovedfromthePhase1bmodels,thuseliminatinginterfacemessagestatesandnumericalvaluesindicatinghowmuchuidhadbeendeliveredinbothpro-cedures.

Thiseliminatedthepossibilityofincorporatingtaskbehaviorrelatedtopumpprimingandbolusadminis-trationinthemodel.

–ThePhase1amodelmimickedthesecurityfeaturesfoundintheoriginaldevicewhichrequiredthehumanoperatortounlockandlockthedeviceonstartupandenterasecu-ritycode.

ThisfunctionalitywasremovedfromthePhase1bmodelwhichreducedthenumberofinterfacemessagesinthemodelandremovedthenumericalvariable(witha0–999range)associatedwithenteringthesecuritycode.

Thiseliminatedthepossibilityofmodelinghumantaskbehaviorrelatedtounlockingandlockingthepumpaswellasenteringthesecuritycodeinthemodel.

–InthePhase1amodel,theinterfacemessagecouldauto-maticallytransitiontobeingblank:mimickingtheactualpump'sabilitytoblankitsscreenafterthreesecondsofoperatorinactivity.

Becausefurtheroperatorinactionwouldresultintheoriginaldeviceissuinga"leftinpro-grammingmode"alert,ablankinterfacemessagecouldautomaticallytransitiontoanalertissuance.

Thisfunction-alitywasremovedfromthePhase1bmodel,eliminatingseveralinterfacemessagesaswellasvariablesthatkepttrackofthepreviousinterfacemessage.

Thus,theoption123Formallyverifyinghuman–automationinteraction225ofmodelingoperatortaskresponsetoscreenblankingandalertswasremovedfromthemodel.

WhilethesereductionsresultedinthePhase1bmodelbeingmuchsmallerandmoremanageablethantheoriginal,theabilitytomodelsomeofthetaskbehaviorsoriginallyasso-ciatedwiththedevicehadtobesacriced.

4.

3ResultsThePhase1bmodelwasabletocompletethevericationprocedurewithEq.

(1)andproduceacounterexamplewithasearchdepthof54inapproximately5.

9h,withthemajorityofthattime(5.

4h)usedforcreatingtheBDDrepresentation[3].

4Notsurprisingly,themodelcheckerranoutofmemorywhenattemptingtoverifyEq.

(2).

5Phase1c:asimplerPCApumpmodelWhilethemodeldevelopedinPhase1bdidproduceusableresultsandhassubsequentlybeenusedinthevericationofadditionalproperties(see[5]),thispowercameattheexpenseofareductioninthescopeofthemissionmodel.

Sincethemissiondirectlyinuenceswhathumanbehaviorwillexe-cute,thislimitedthehumantaskbehaviorthatcouldulti-matelybeveriedaspartofthesystemmodel.

Further,thefactthatthePhase1bmodelwastoocomplexforEq.

(2)tobeveriedpotentiallylimitedanyfuturemodeldevelopmentthatmightaddcomplexity.

Toremedytheseshortcoming,themodelproducedinPhase1bwasfurtherreducedtoonethatencompassedtheprogrammingofthemostbasicPCApumpfunctionalitywhiletherangesofpossiblevaluesfortheremainingmissionmodelvariableswereexpandedtobemorerealistic.

5.

1ModelreductionToobtainasmallerPCAmodel,allofthefollowingwereremoved:theselectionofmodeandtheabilitytospecifyabasalrate,continuousrate,bolusdosage,anduidvolume.

Asaresult,associatedinterfacemessagesandvariableswereremovedalongwiththeabilitytomodeltheirprogrammingaspartofthehumantaskbehaviormodel.

ThisresultedinamodelthatonlyencompassedfunctionalityforprogrammingaPCAdose,programmingthedelaybetweenPCAdoses,turningthepumponandoff,andstartingandstoppingtheadministrationoftreatment:functionalitycompatiblewiththemostbasicPCApumpoperations(see[1]).

4Completedmodels,SALoutputs,andcounterexamplescanbefoundathttp://cog.

sys.

virginia.

edu/ISSE2010/.

Valuerangeswerefurtherrestrictedtoreducethesizeofthemodel.

Specifically,theupperboundontheacceptabledelaybetweenPCAdosageswaschangedfrom240to60minutes.

This,coupledwiththeotherreductions,hadtheaddedbenetofallowingthenumberofdigitsrequiredfortheprogrammingofpumpvaluestobereducedto2ratherthantheoriginal4.

ThereductionsinotherareasallowedthescopeofthedelaysandPCAdosagesgeneratedbythemissionmodeltobeexpandedtoamorerepresentativeset.

ForPCAdosages,thefullrangeofvaluesfrom0.

1to9.

9in0.

1mlincrementsweresupported.

Fordelaybetweendosages,veoptionswereavailable:delaysof10,15,30,45,and60min.

Allpumpinterfacefunctionalitywasretainedfromthepreviousmodels.

Thus,theunconstrainedhumantaskmodelwasunchangedaswasthehumantaskandHDImodels'communicationprotocol.

5.

2ResultsThePhase1cmodelranthevericationprocedureforEq.

(1)(withtheeliminatedvariablesremoved)in6swithasearchdepthof22,muchfasterthanthemodelfromPhase1b.

ThevericationofthespecicationinEq.

(2)veriedtotruein129swithasearchdepthof259and78,768,682,750visitedstates.

6Phase2:incorporatingmodelsofhumanbehaviorInthesecondphaseofmodeling,weexpandedourinstantia-tionoftheframeworkbyincorporatingarealistichumantaskbehaviormodel.

WethereforereplacedtheunconstrainedhumanoperatorinthePhase1cmodelwithahumantaskbehaviormodelderivedfrompumpdocumentation[2]andtrainingmaterials.

ThismodelutilizedtheEOFMconceptsandthusrequiredsomeadditionalinfrastructureinordertoincorporateitintotheformalsystemmodel.

Wedescribethebehaviorsthatweremodeled,howtheseweretranslatedintotheformalmodel,andreportvericationresultsforthepro-ducedsystemmodel.

6.

1HumantaskbehaviormodelingandtranslationThepump'smaterialscontainedsixhigh-levelgoaldirectedbehaviorsforperformingavarietyofpumpactivitiesrelevanttothePhase1cmodelasfollows:–Turningonthepump.

–Stoppingtheinfusionofmedication.

–Turningoffthepump.

–EnteringaprescribedvalueforPCAdosagevolumes(inmilliliter).

123226M.

L.

Bolton,E.

J.

Bass–EnteringaprescribedvalueforthedelaybetweenPCAdoses(inminutes),and–Selectingwhethertostartorreviewanenteredprescrip-tion.

TheEOFMmodelsdescribingeachofthesebehaviorsarediscussedbelow.

6.

1.

1TurningOnthepumpThemodelforturningonthepumpisshowninFig.

3.

Here,theEOFMcanexecuteiftheinterfacemessageindi-catesthatthesystemisoff(iInterfaceMessage=SystemOff;aprecondition).

Thishigh-levelactivity(aTurnOnPump)iscompletedbyperformingtheactionofpressingtheon/offbutton(hPressOnOff).

Theorddecompositionoperatorindi-catesthatallofthedecomposedactivitiesoractionsmustbecompletedinsequentialorder.

TheEOFMhasaccomplisheditsgoal(acompletioncondition)whentheinterfacemes-sageindicatesthatthepumpisnolongeroff(iInterfaceMes-sage/=SystemOff).

6.

1.

2StoppinginfusionInfusionofmedicationcanbestopped(Fig.

4)iftheinter-faceindicatesthattreatmentisadministering(iInterfaceMes-sage=TreatmentAdministering).

Thisisaccomplishedbypressingthestopbutton(hPressStop)twiceinquicksuc-cessionwithnootherhumaninputsoccurringinbetween.

Theprocesshascompletedwhentheinterfaceindicatesthattreatmentisnotadministering(iInterfaceMessage/=Treat-mentAdministering).

aTurnOnPumpiInterfaceMessage=SystemOffiInterfaceMessage/=SystemOffordhPressOnOffFig.

3TheEOFMgraphicalrepresentationforturningonthepumpaStopInfusingiInterfaceMessage=TreatmentAdministeringiInterfaceMessage/=TreatmentAdministeringordhPressStophPressStopFig.

4TheEOFMgraphicalrepresentationforstoppinginfusion6.

1.

3TurningOffthepumpThemodelforturningoffthepump(Fig.

5)isrelevantiftheinterfacemessageindicatesthatthesystemisnotoff(iIn-terfaceMessage/=SystemOff).

Thepumpisturnedoffbyperformingtwolowerlevelactivitiesinsequentialorder:stoppinginfusion(aStopInfusion;explainedabove)andpressingthekeysnecessarytoturnoffthepump(aPress-KeysToTurnOffPump).

Thislatteractivityiscompletedbypressingtheon/offbutton(hPressOnOff)twiceinsequence.

Theentireprocessofturningoffthepumpcompleteswhentheinterfaceindicatesthatthepumpisoff(iInterfaceMes-sage=SystemOff).

6.

1.

4ProgrammingavalueintothepumpThevaluesforPCAdosagevolumeanddelaybetweendosagescanbeprogrammedintothepumpusinganEOFMpatternedafterFig.

6.

Thus,foragivenvalueX,thecorre-spondingEOFMbecomesrelevantwhentheinterfaceforsettingthatvalueisdisplayed(iInterfaceMessage=SetX).

Thisisachievedbysequentiallyexecutingtwosub-activities:changingthedisplayedvalue(aChangeXValue)andaccept-ingthedisplayedvalue(aAccept).

Theactivityforchangingthedisplayedvaluecanexecute,andwillrepeatedlyexecute,ifthedisplayedvalueisnotequaltotheprescribedvalue(iCurrentValue/=iPrescribedX).

Thevalueischangedbyexecutingoneormore(denotedbytheor_seqdecomposi-tionoperator)ofthefollowingsub-activities:changingthedigitcurrentlypointedtobythecursor(aChangeDigit:com-pletedbypressingtheupkey(hPressUp)),movingthecursortoadifferentdigit(aNextDigit:completedbypressingonlyoneof(thexordecompositionoperator)theleft(hPress-Left)orright(hPressRight)buttons),orsettingthedisplayedvaluetozero(aClearValue:completedbypressingtheclearbutton(hPressClear)).

Theprocessofchangingthedisplayed123Formallyverifyinghuman–automationinteraction227aTurnOffPumpiInterfaceMessage/=SystemOffiInterfaceMessage=SystemOffordaStopInfusingiInterfaceMessage=TreatmentAdministeringiInterfaceMessage/=TreatmentAdministeringordhPressStophPressStopaPressKeysToTurnOffPumpordhPressOnOffhPressOnOffFig.

5TheEOFMgraphicalrepresentationforturningoffthepumpvaluecompleteswhenthedisplayedvaluematchesthepre-scribedvalue(iCurrentValue=iPrescribedX).

Thedisplayedvalueisacceptedbypressingtheenterkey.

Theentirepro-cessendswhentheinterfaceisnolongerinthestateforacceptingX.

6.

1.

5StartingorreviewingaprescriptionAfteraprescriptionhasbeenprogrammedthehumanopera-torisgiventheoptiontostarttheadministrationofthatpre-scriptionortoreviewit(wheretheoperatorworksthroughtheprogrammingprocedureasecondtimewiththepreviouslyprogrammedoptionsdisplayedateachstep).

TheEOFMforperformingthis(Fig.

7)becomesrelevantatthispoint(iInter-faceMessage=StartBeginsRx).

Itiscompletedbyperform-ingonlyoneoftwoactivities:selectingtheoptiontostarttreatment(aStartRx—performedbypressingthestartbutton(hPressStart))orselectingthereviewoption(aReviewRx—performedbypressingtheenterbutton(hPressEnter)).

6.

2EOFMtranslationTheEOFMsrepresentingthehumantaskmodelweretranslatedintoaSALcodemodule.

ThistranslationwasaccomplishedbycreatingavariableforeachactivityoractionnodeineachEOFM,eachofwhichcouldassumeoneofthreeenumeratedvaluesdescribingitsexecutionstate:ready,exe-cuting,ordone.

Thus,inadditiontohandlingthetransitionallogicforthecoordinationprotocol,thismodulehandledthetransitionlogicforallowingthevariablesrepresentingactivityandactionnodestotransitionbetweenthesethreevalues.

Allactivityandactionvariablesstartinthereadystate.

Theycantransitionbetweenexecutionstatesbasedontheexecutionstateoftheirchildren,parent,andsiblingsintheEOFMstructure;theevaluationoftheirconditions;andtheirpositionwithintheEOFMhierarchy.

Whiletheresultinghumanoperatormoduleanditsassoci-atedunconstrainedoperatormodelbothhadthesameinputsandoutputs,thelogicassociatedwithtraversalofthehumantaskstructuresrequired48additionalvariablesinthehumantaskbehaviormodel.

6.

3ResultsThespecicationinEq.

(1)veried(producedtheexpectedcounterexample)in57swithasearchdepthof42.

Thespec-icationinEq.

(2)veriedtotruein10.

6hwithasearchdepthof437and1,534,862,538visitedstates.

7DiscussionThisworkhasshownthatitispossibleforhuman–automationinteractiontobeevaluatedusingthearchitectureinFig.

1.

However,thiscameasaresultoftradeoffsbetweenthegoalsthearchitectureisdesignedtosupport:123228M.

L.

Bolton,E.

J.

BassaSetXiInterfaceMessage=SetXiInterfaceMessage/=SetXordaChangeXValueiCurrentValue/=iPrescribedXiCurrentValue/=iPrescribedXiCurrentValue=iPrescribedXor_seqaChangeDigitordhPressUpaSelectNextDigitxorhPressLefthPressRightaClearValueordhPressClearaAcceptordhPressEnterFig.

6TheEOFMgraphicalrepresentationofthepatternforprogrammingavalueXintothepump1.

Modelconstructsneedtobeintuitivetohumanfactorsengineerswhowillbebuildingandevaluatingmanyofthemodels;2.

thesub-modelsshouldbedecoupledandmodular(asinFig.

1)inordertoallowforinterchangeabilityofalter-nativesub-models;and3.

theconstructedmodelsneedtobecapableofbeingver-iedinareasonableamountoftime.

Wediscusshoweachofthesegoalswasimpactedandhowrelatedissuesmightbeaddressed.

7.

1Goals1:modelintuitivenessManyofthemodelrevisionswereassociatedwithrepresent-ingmodelconstructsinwaysthatweremorereadilyinter-pretablebythemodelcheckerratherthanthehumanfactorsengineer.

Theseprimarilytooktheformofconvertingoat-ingpointanddigitarrayvaluesintointegersinPhase1b.

Further,theextensivemodelreductionsthatwereundertakeninPhase1cwouldbeverycumbersomeforahumanfactorsengineer.

Therearetwopotentialwaystoaddressthisissue.

Onesolutionwouldbetoimprovethemodelcheckersthemselves.

Giventhatthemodicationswouldnotactuallychangethenumberofreachablestatesinthesystem,thiswouldsuggestthatthemodelcheckerneedonlyoptimizetheBDDconver-sionalgorithms.

Alternatively,additionalmodelingtoolscouldbeusedtohelpmitigatethesituation.

SuchtoolscouldallowhumanfactorsengineerstoconstructorimportHDIprototypes,andtranslatethemintomodelcheckercode.

Thiswouldallowtheunintuitiverepresentationsnecessaryforensuringamodel'sefcientprocessingbythemodelcheckertoberemovedfromthemodeler'sview.

123Formallyverifyinghuman–automationinteraction229aStartOrReviewiInterfaceMessage=StartBeginsRxiInterfaceMessage/=StartBeginsRxxoraStartRxordhPressStartaReviewRxordhPressEnterFig.

7TheEOFMforchoosingtostartorreviewaprescription7.

2Goal2:decouplingofarchitecturesub-modelsBecausetheprotocolusedtocoordinatehumanactionsbetweentheHDIandhumantaskmodels(discussedforPhase1aandusedinallmodelsproducedinallsubsequentphases)assumesaparticularrelationshipbetweenvariablessharedbythesemodels,theyaretightlycoupled.

Unlessamodelcheckercanbemadetosupportbothasynchronousandsynchronousrelationshipsbetweenmodelsmoreelegantly,thiscoordinationinfrastructurecannotbeeliminated.

However,asolutionmaybefoundinanadditionallevelofabstraction.

AtoolsetfortranslatingaHDIprototypeintomodelcheckingcode,couldhandletheconstructionofthecoordinationprotocol,makingthisprocesseffectivelyinvis-ibletothemodeler.

SuchaprocesscouldalsoallowformoreefcientmeansofcoordinatingtheHDIandhumantaskmod-els:onethatmightnotrequiretheuseofseparatemodelsintheactualmodelcheckercode.

WhiletheextensivemodelreductionsfromPhase1greatlydiminishedthedelitywithwhichthemodelrepresentedtheactualPCApump,thisprovidessomeadvantages.

SincethemodelfromPhase2doesnotsufferfromthememoryusageproblemsencounteredinPhase1,thisopensthedoortotheadditionofothermodelconstructstobeaddedallowingforamorecompletesystemanalysis.

FutureworkcanexpandthemodeldevelopedinPhase2withenvironmentalanddeviceautomationmodelsthatarecompatiblewiththeformalPCApumpreferencemodeldescribedin[1].

7.

3Goal3:modelveriabilityWearepredominantlyconcernedwithexploringhowformalmethodscanbeusedtoprovideinsightsintohumanfactorsandsystemsengineeringconcerns.

Ifourgoalwastofor-mallyverifypropertiesoftheBaxterIpump,themodelingcompromiseswemadeinordertoobtainaveriablemodelmightnecessitateachangeinmodelingphilosophyorveri-cationapproach.

Therearemanybarrierstotheveriabilityofmodelsofrealisticsystems.

Theseincludelargenumbersofparallelprocesses,largerangesofdiscretevaluedvariables,andnon-discretelyvaluedvariables.

Themodelingeffortsdescribedhereweresochallengingbecausethetargetsystemwasdependentonalargenumberofuserspeciednumericalvalues,allofwhichhadverylargeacceptableranges.

Thisresultedinthescopeofthemodelbeingreducedtothepointwhereitcouldnolongerbeusedforverifyingalloftheorigi-nalhumanoperatortaskbehaviors:withthemodelproducedinPhase1bmakingminorcompromisesandthemodelpro-ducedinPhase1conlyallowingforbehaviorsassociatedwithbasicPCApumpfunctionality.

AswasdemonstratedinPhase2,theveriabilityofthemodelactuallyincreasedwiththeinclusionofthehumantaskbehaviorasindicatedbythe98%reductioninthereportedstatespacefromthePhase1ctothePhase2model.

However,thiscameattheexpenseoftheverica-tionprocesstaking284timesaslong.

Thus,inacontextwherevericationtimeislessimportantthanthesizeofthemodel'sstatespace,theinclusionofthehumantaskbehaviormodelmaygenerallyprovetobeadvantageousinthefor-malvericationofsystemsthathaveahuman–automationinteractioncomponent,irrespectiveofwhetherthehumanbehaviorisofconcerninthevericationprocess.

Futureeffortsshouldinvestigatethedifferentfactorsthataffectthistradeoff.

Evenexploitingthisadvantage,therelativesimplicityofthedevicethatwasmodeledinthisworkmakesitclearthattherearemanysystemsthatdependofhuman–auto-mationinteractionthatwouldbeevenmorechallengingtoverify,ifnotimpossible,usingthesetechniques.

Whiletheuseofboundedmodelcheckersmayprovidesomeverica-tioncapabilitiesforcertainsystems,thereislittlethatcanbedonewithouteitherusingadditionalabstractiontechniquesorfutureadvancesinmodelcheckingtechnologyandcom-putationpower.

Itiscommonpracticeintheformalmethodscommunitytousemoreadvancedformsofdataabstractionthanthoseemployedinthisworktomitigatethecomplexityofvari-ableswithlargevalueranges(anoverviewofthesemethodscanbefoundin[20]).

Becausethenatureofthemodeledhumantaskbehaviorinthisworkwasconcernedwiththedigitleveleditingofthedatavalues,suchabstractionswere123230M.

L.

Bolton,E.

J.

Bassnotappropriateforthisparticularendeavor.

Additionally,automaticpredicateabstractiontechniqueslikethoseusedincounterexample-guidedabstractionrenement[6]couldpotentiallyalleviatesomeofthecomplexityproblemsenco-unteredinthisworkwithoutrequiringchangestothemodelsthemselves.

Futureworkshouldinvestigatehowthesedif-ferentabstractiontechniquescouldbeusedwhenmodelingsystemsthatdependonhuman-automationinteractioninwaysthatareintuitivetohumanfactorsengineers.

Itisclearthatthemultiple,large-value-rangedvariableswerethesourceofmostofthemodelcomplexityproblemsinthepumpexample,asshowninthedrasticdecreaseinver-icationperformancetimebetweenthemodelsproducedinPhases1band1c.

Thus,hadthetargetsystembeenmorecon-cernedwithproceduralbehaviorsandlessontheinterrela-tionshipsbetweennumericalvalues,thesystemmodelwouldhavebeenmuchmoretractable.

Futureworkshouldidentifyadditionalpropertiesofsystemsdependentonhuman–auto-mationinteractionthatlendthemselvestobeingmodeledandveriedusingtheframeworkdiscussedhere.

Finally,someoftheperformanceissuesweencounteredcanbeattributedtoouruseofSAL.

Forexample,modelcheckerssuchasSPIN[15]donotperformthelengthypro-cessofconstructingtheBDDrepresentationbeforestartingthecheckingprocess.

Futureworkshouldinvestigatewhichmodelcheckerisbestsuitedforevaluatinghuman–automa-tioninteraction.

8ConclusionTheworkpresentedherehasshownthatitispossibletocon-structmodelsofhuman–automationinteractionaspartofalargersystemforuseinformalvericationprocesseswhileadheringtosomeofthearchitecturalgoalsinFig.

1.

Ithasalsoshownthattheincorporationofhumantaskbehaviormodelsintosystemmodelsmayhelpalleviatethestateexplosionprobleminsomesystemsthatdependonhuman–automationinteraction.

However,thissuccesswastheresultofanumberofcompromisesthatproducedamodelthatwasnotasrep-resentative,understandable,ormodularasdesired.

Thus,inorderforformalmethodstobecomemoreusefulfortheHFEcommunity,thevericationtechnologywillneedtobeabletosupportamorediversesetofsystems.

Further,newmodelingtoolsmayberequiredtosupportrepresentationsthathumanfactorsengineersuse.

Theseadvanceswillultimatelyallowformalmethodstobecomeamoreusefultoolforhumanfactorsengineersworkingwithsafetycriticalsystems.

AcknowledgmentsTheresearchdescribedwassupportedinpartbyGrantNumberT15LM009462fromtheNationalLibraryofMedicineandResearchGrantAgreementUVA-03-01,sub-award2623-VAfromtheNationalInstituteofAerospace(NIA).

Thecontentissolelytheresponsibilityoftheauthorsanddoesnotnecessarilyrepresenttheof-cialviewsoftheNIA,NASA,theNationalLibraryofMedicine,ortheNationalInstitutesofHealth.

TheauthorswouldliketothankRaduI.

SiminiceanuoftheNIAandBenDiVitooftheNASALangleyResearchCenterfortheirtechnicalhelp.

TheywouldliketothankDianeHaddon,JohnKnapp,PaulMerrel,KathrynMcGough,andSherryWoodoftheUniversityofVirginiaHealthSystemfordescribingthefunctionalityoftheBaxterIpumpandforprovidingdocumentation,trainingmaterials,anddeviceaccess.

OpenAccessThisarticleisdistributedunderthetermsoftheCreativeCommonsAttributionNoncommercialLicensewhichpermitsanynoncommercialuse,distribution,andreproductioninanymedium,providedtheoriginalauthor(s)andsourcearecredited.

References1.

ArneyD,JetleyR,JonesP,LeeI,SokolskyO(2007)Formalmeth-odsbaseddevelopmentofaPCAinfusionpumpreferencemodel:genericinfusionpump(GIP)project.

In:Proceedingsofthe2007jointworkshoponhighcondencemedicaldevices,software,andsystemsandmedicaldeviceplug-and-playinteroperability.

IEEEComputerSociety,Washington,DC,pp23–332.

BaxterHealthCareCorporation(1995)Ipumppainmanage-mentsystemoperator'smanual.

BaxterHeathCareCorporation,McGawPark3.

BoltonML,BassEJ(2009)Buildingaformalmodelofahuman-interactivesystem:insightsintotheintegrationofformalmethodsandhumanfactorsengineering.

In:ProceedingsoftherstNASAformalmethodssymposium.

NASAAmesResearchCenter,Moff-ettField,pp6–154.

BoltonML,BassEJ(2009)Enhancedoperatorfunctionmodel:agenerichumantaskbehaviormodelinglanguage.

In:Proceed-ingsoftheIEEEinternationalconferenceonsystems,man,andcybernetics.

IEEE,Piscataway,pp2983–29905.

BoltonML,BassEJ(2009)Amethodfortheformalvericationofhuman-interactivesystems.

In:Proceedingsofthe53rdannualmeetingofthehumanfactorsandergonomicssociety.

HumanFac-torsandErgonomicsSociety,SantaMonica,pp764–7686.

ClarkeE,GrumbergO,JhaS,LuY,VeithH(2003)Counterexam-ple-guidedabstractionrenementforsymbolicmodelchecking.

JACM50(5):752–7947.

CrowJ,JavauxD,RushbyJ(2000)Modelsandmechanizedmeth-odsthatintegratehumanfactorsintoautomationdesign.

In:Pro-ceedingsofthe2000internationalconferenceonhuman-computerinteractioninaeronautics.

AssociationfortheAdvancementofArticialIntelligence,MenloPark,pp163–1688.

CurzonP,RuksenasR,BlandfordA(2007)Anapproachtoformalvericationofhuman–computerinteraction.

FormalAspComput19(4):513–5509.

DeMouraL,OwreS,ShankarN(2003)TheSALlanguagemanual.

Technicalreport,ComputerScienceLaboratory,SRIInternational,MenloPark10.

DeganiA(1996)Modelinghuman–machinesystems:onmodes,error,andpatternsofinteraction.

PhDthesis,GeorgiaInstituteofTechnology,Atlanta11.

DeganiA,KirlikA(1995)Modesinhuman–automationinterac-tion:Initialobservationsaboutamodelingapproach.

In:Proceed-ingsoftheIEEEinternationalconferenceonsystems,manandcybernetics.

IEEE,Piscataway,pp3443–345012.

FieldsRE(2001)Analysisoferroneousactionsinthedesignofcriticalsystems.

PhDthesis,UniversityofYork,York13.

HeymannM,DeganiA(2007)Formalanalysisandautomaticgen-erationofuserinterfaces:approach,methodology,andanalgo-rithm.

HumFactors49(2):311–330123Formallyverifyinghuman–automationinteraction23114.

HeymannM,DeganiA,BarshiI(2007)Generatingproceduresandrecoverysequences:aformalapproach.

In:Proceedingsofthe14thinternationalsymposiumonaviationpsychology.

AssociationforAviationPsychology,Dayton,pp252–25715.

HolzmannGJ(2003)Thespinmodelchecker,primerandreferencemanual.

Addison-Wesley,Reading16.

JavauxD(2002)Amethodforpredictingerrorswheninteractingwithnitestatesystems.

Howimplicitlearningshapestheuser'sknowledgeofasystem.

ReliabEngSystSaf75(2):147–16517.

KirwanB,AinsworthLK(1992)Aguidetotaskanalysis.

TaylorandFrancis,Philidelphia18.

KohnLT,CorriganJ,DonaldsonMS(2000)Toerrishuman:build-ingasaferhealthsystem.

NationalAcademyPress,Washington19.

KreyN(2007)2007Nallreport:accidenttrendsandfactorsfor2006.

Technicalreport.

http://download.

aopa.

org/epilot/2007/07nall.

pdf20.

Mansouri-SamaniM,PasareanuCS,PenixJJ,MehlitzPC,O'MalleyO,VisserWC,BratGP,MarkosianLZ,PressburgerTT(2007)Programmodelchecking:apractitioner'sguide.

Techni-calreport,IntelligentSystemsDivision,NASAAmesResearchCenter,MoffettField21.

MitchellCM,MillerRA(1986)Adiscretecontrolmodelofoper-atorfunction:amethodologyforinformationdislaydesign.

IEEETransSystManCybernASystHum16(3):343–35722.

PerrowC(1984)Normalaccidents.

BasicBooks,NewYork23.

RushbyJ(2002)Usingmodelcheckingtohelpdiscovermodeconfusionsandotherautomationsurprises.

ReliabEngSystSaf75(2):167–17724.

SchraagenJM,ChipmanSF,ShalinVL(2000)Cognitivetaskanalysis.

LawrenceErlbaumAssociates,Mahwah25.

StantonN(2005)Humanfactorsmethods:apracticalguideforengineeringanddesign.

AshgatePublishing,Brookeld26.

ThurmanDA,ChappellAR,MitchellCM(1998)AnenhancedarchitectureforOFMspert:adomain-independentsystemforintentinferencing.

In:ProceedingsoftheIEEEinternationalconferenceonsystems,man,andcybernetics.

IEEE,Piscataway,pp3443–345027.

VicenteKJ(1999)Cognitiveworkanalysis:towardsafe,produc-tive,andhealthycomputer-basedwork.

LawrenceErlbaumAsso-ciates,Mahwah28.

WellsAT,RodriguesCC(2004)Commercialaviationsafety,4thedn.

McGraw-Hill,NewYork29.

WickensCD,LeeJ,LiuYD,Gordon-BeckerS(2003)Introductiontohumanfactorsengineering.

Prentice-Hall,UpperSaddleRiver123

1007/s11334-010-0129-9ORIGINALPAPERFormallyverifyinghuman–automationinteractionaspartofasystemmodel:limitationsandtradeoffsMatthewL.

Bolton·EllenJ.

BassReceived:8March2010/Accepted:25March2010/Publishedonline:9April2010TheAuthor(s)2010.

ThisarticleispublishedwithopenaccessatSpringerlink.

comAbstractBoththehumanfactorsengineering(HFE)andformalmethodscommunitiesareconcernedwithimprovingthedesignofsafety-criticalsystems.

Thisworkdiscussesamodelingeffortthatleveragedmethodsfrombotheldstoperformformalvericationofhuman–automationinter-actionwithaprogrammabledevice.

Thiseffortutilizesasystemarchitecturecomposedofindependentmodelsofthehumanmission,humantaskbehavior,human-deviceinter-face,deviceautomation,andoperationalenvironment.

ThegoalsofthisarchitectureweretoallowHFEpractitionerstoperformformalvericationsofrealisticsystemsthatdependonhuman–automationinteractioninareasonableamountoftimeusingrepresentativemodels,intuitivemodelingcon-structs,anddecoupledmodelsofsystemcomponentsthatcouldbeeasilychangedtosupportmultipleanalyses.

Thisframeworkwasinstantiatedusingapatientcontrolledanal-gesiapumpinatwophasedprocesswheremodelsineachphasewereveriedusingacommonsetofspecications.

Therstphasefocusedonthemission,human-deviceinterface,anddeviceautomation;andincludedasimple,unconstrainedhumantaskbehaviormodel.

Thesecondphasereplacedtheunconstrainedtaskmodelwithonerepresentingnormativepumpprogrammingbehavior.

Becausemodelsproducedintherstphaseweretoolargeforthemodelcheckertoverify,anumberofmodelrevisionswereundertakenthataffectedthegoalsoftheeffort.

Whiletheuseofhumantaskbehaviormodelsinthesecondphasehelpedmitigatemodelcomplex-ity,vericationtimeincreased.

AdditionalmodelingtoolsM.

L.

Bolton(B)·E.

J.

BassDepartmentofSystemsandInformationEngineering,UniversityofVirginia,151Engineer'sWay,Charlottesville,VA,USAe-mail:mlb4b@virginia.

eduE.

J.

Basse-mail:ejb4n@virginia.

eduandtechnologicaldevelopmentsarenecessaryformodelcheckingtobecomeamoreusabletechniqueforHFE.

KeywordsHuman–automationinteraction·Taskanalysis·Formalmethods·Modelchecking·Safetycriticalsystems·PCApump1IntroductionBothhumanfactorsengineering(HFE)andformalmethodsareconcernedwiththeengineeringofrobustsystemsthatwillnotfailunderrealisticoperatingconditions.

Thetraditionaluseofformalmethodshasbeentoevaluateasystem'sauto-mationunderdifferentoperatingand/orenvironmentalcon-ditions.

However,humanoperatorscontrolanumberofsafetycriticalsystemsandcontributetounforeseenproblems.

Forexample,humanbehaviorhascontributedtobetween44,000and98,000deathsnationwideeveryyearinmedicalpractice[18],74%ofallgeneralaviationaccidents[19],atleasttwo-thirdsofcommercialaviationaccidents[28],andanumberofhighproledisasterssuchastheincidentsatThreeMileIslandandChernobyl[22].

HFEfocusesonunderstandinghumanbehaviorandapplyingthisknowledgetothedesignofhuman–automationinteraction:makingsystemseasiertousewhilereducingerrorsand/orallowingrecoveryfromthem[25,29].

ByleveragingtheknowledgeofbothHFEandformalmethods,researchershaveidentiedthecognitiveprecon-ditionsformodeconfusionandautomationsurprise[7,10,16,23];automaticallygenerateduserinterfacespecications,emergencyprocedures,andrecoverysequences[13,14];andidentiedhumanbehaviorsequences(normativeorerrone-ous)thatcontributetosystemfailures[8,12].

123220M.

L.

Bolton,E.

J.

BassWhileallofthisworkhasproducedusefulresults,themodelshavenotincludedallofthecomponentsnecessarytoanalyzehuman–automationinteraction.

ForHFEanalysesofhuman–automationinteraction,theminimalsetofcom-ponentsarethegoalsandproceduresofthehumanopera-tor;theautomatedsystemanditshumaninterface;andtheconstraintsimposedbytheoperationalenvironment.

Cogni-tiveworkanalysisisconcernedwithidentifyingconstraintsintheoperationalenvironmentthatshapethemissiongoalsofthehumanoperator[27];cognitivetaskanalysisiscon-cernedwithdescribinghowhumanoperatorsnormativelyanddescriptivelyperformgoalorientedtaskswheninteract-ingwithanautomatedsystem[17,24];andmodelingframe-workssuchas[11]seektonddiscrepanciesbetweenhumanmentalmodels,human-deviceinterfaces(HDIs),anddeviceautomation.

Inthiscontext,problemsrelatedtohuman–automationinteractionmaybeinuencedbythehumanoperator'smission,thehumanoperator'staskbehavior,theoperationalenvironment,theHDI,thedevice'sautomation,andtheirinterrelationships.

Wearedevelopingmethodsandtoolstoallowhumanfactorsengineerstoexploittheirexistinghumantaskmodelingconstructswiththepowerfulvericationcapabil-itiesofformalmethodsinordertoidentifypotentialprob-lemswithhuman–automationinteractioninsafetycriticalsystemsthatmayberelatedtohumantaskbehavior,theautomateddevice,theoperationalenvironment,ortheirinter-action.

Tothisend,wearedevelopingacomputationalframe-work(Fig.

1)fortheformalmodelingofhuman-automationinteraction.

Thisframeworkutilizesconcurrentmodelsofhumanoperatortaskbehavior,humanmission(thegoalstheoperatorwishestoachieveusingthesystem),deviceauto-mation,andtheoperationalenvironmentwhicharecom-posedtogethertoformalargersystemmodel.

Inter-modelinteractionisrepresentedbyvariablessharedbetweenmod-els.

Environmentvariablescommunicateinformationaboutthestateoftheenvironmenttothedeviceautomation,mis-sion,andhumantaskmodels.

Missionvariablescommuni-catethemissiongoalstothehumantaskmodel.

InterfacevariablesconveyinformationaboutthestateoftheHDI(dis-playedinformation,thestateofinputwidgets,etc.

)tothehumantaskmodel.

ThehumantaskmodelindicateswhenandwhatactionsahumanoperatorwouldperformontheHDI.

TheHDIcommunicatesitscurrentstatetothedeviceauto-mationviatheinterfacevariables.

TheHDIreceivesinfor-mationaboutthestateofthedeviceautomationmodelviatheautomationstatevariables.

Forbroaderapplicability,theanalysisframeworkmustsupportmodelingconstructsintuitivetothehumanfac-torsengineerinordertoallowhimtoeffectivelymodelhumanmissions,humantasks,andHDIs.

Becauseanengi-neermaywishtorerunvericationsusingdifferentmissions,taskmodels,HDIs,environments,orautomationbehaviors,thesecomponentsshouldremaindecoupled(asisthecaseinFig.

1).

Finally,themodelingtechniquemustbecapableofrepresentingthetargetsystemswithenoughdelitytoallowtheengineertoperformthedesiredverication,anddosoinareasonableamountoftime(thiscouldmeanseveralhoursforasmallproject,orseveraldaysforamorecomplicatedone).

ThispaperdescribesaninstantiationofthisframeworkusingamodelofaBaxterIpumpPainManagementSystem[2],apatientcontrolledanalgesia(PCA)pumpthatadminis-terspainmedicationinaccordancewithconstraintsdenedbyahealthcaretechnician(describedinSect.

2.

1).

Modelsweredevelopedintwophases.

TherstphaseinvolvedtheconstructionanddebuggingoftheHDI,deviceautomation,andhumanmissionmodels(anenvironmentalmodelwasnotSystemModelHumanTaskModelDeviceAutomationModelHuman-DeviceInterfaceModelMissionModelEnvironmentModelMissionVariablesHumanActionVariablesInterfaceVariablesInterfaceVariablesAutomationStateVariablesEnvironmentVariablesFig.

1Frameworkfortheformalmodelingofhuman–automationinteraction.

Arrowsbetweenmodelsrepresentvariablesthataresharedbetweenmodels.

Thedirectionofthearrowindicateswhethertherep-resentedvariablesaretreatedasinputsoroutput.

Ifthearrowissourcedfromamodel,therepresentedvariablesareoutputsofthatmodel.

Ifthearrowterminatesatamodel,therepresentedvariablesareinputstothatmodel123Formallyverifyinghuman–automationinteraction221includedbecauseofthegeneralstabilityoftheenvironmentinwhichanactualpumpoperates)withanunconstrainedhumantaskmodelservingasaplaceholderforamorereal-istichumantaskmodel.

Thesecondextendedthemodelpro-ducedinPhase1witharealisticmodelofthehumantask,completingtheframework.

Eventhoughthetargetdeviceinthismodelingeffortwasseeminglysimple,thesystemmodelthatwasinitiallydevel-opedinPhase1(Phase1a)wastoodifcultforthemodelcheckertoprocessquicklyandtoocomplexforittoverify.

Thusanumberofrevisionswereundertaken[3].

InPhase1bareducedandabstractedmodeloftheBaxterIpumpwasproducedwhich,whilecapableofbeingusedinsomever-ications,didsoattheexpenseoflimitingthenumberofgoalsrepresentedinthehumanmissionmodel.

ThisPhase1bmodellimitedtheusefulnessofincorporatinghumantaskbehaviorinPhase2.

Thus,inPhase1c,thesystemmodelwasreducedtoencompasstheprogrammingprocedureforamuchsimplerPCApump.

InPhase2,theincorporationofthemorerealistichumantaskbehavioractuallyresultedinareductionofthetotalsystemmodel'scomplexity,butdidsoattheexpenseofanincreaseinvericationtime.

Thispaperdiscussesthesemodelingphases,thevericationresultspro-ducedinthem,andtheirassociatedcompromisesinrelationtothegoalsofthemodelingarchitecture.

Theseareusedtodrawconclusionsaboutthefeasibilityofusingformalmeth-odstoinformhuman–automationinteraction.

2Methods2.

1ThetargetsystemTheBaxterIpumpisanautomatedmachinethatcontrolsdeliveryofsedative,analgesic,andanestheticmedicationsolutions[2].

Solutiondeliveryviaintravenous,subcutane-ous,andepiduralroutesissupported.

Medicationsolutionsaretypicallystoredinbagslockedinacompartmentonthebackofthepump.

Pumpbehaviorisdictatedbyinternalautomation,whichcandependonhowthepumpisprogrammedbyahumanoperator.

PumpprogrammingisaccomplishedviaitsHDI(Fig.

2)whichcontainsadynamicLCDdisplay,asecu-ritykeylock,andeightbuttons.

Whenprogrammingthepump,theoperatorisabletospecifyallofthefollowing:whethertouseperiodicorcontinuousdosesofmedications(i.

e.

,themodewhichcanbePCA,Basal+PCA,orContinu-ous),whethertouseprescriptioninformationpreviouslypro-grammedintothepump,theuidvolumecontainedinthemedicationbag,theunitsofmeasureusedfordosage(ml,mg,org),whetherornottoadministerabolus(aninitialdoseofmedication),dosageamounts,dosageowrates(foreitherbasalorcontinuousratesasdeterminedbythemode),StartStopEnterOn/OffClearCLCDDisplayInterfaceMessageDisplayedValueCursorSecurityKeyLeftButtonUp(Scroll)ButtonRightButtonClearButtonStartButtonStopButtonEnterButtonOn/OffButtonFig.

2AsimpliedrepresentationoftheBaxterIpump'shuman-deviceinterface.

Notethattheactualpumpcontainsadditionalcontrolsandinformationconveyancesthedelaytimebetweendosages,and1hlimitsontheamountofdeliveredmedication.

Duringprogramming,thesecuritykeyisusedtolockandunlockthecompartmentcontainingthemedicationsolution.

Theunlockingandlockingprocessisalsousedasasecuritymeasuretoensurethatanauthorizedpersonisprogrammingthepump.

Thestartandstopbuttonsareusedtostartandstopthedeliveryofmedicationatspecictimesduringpro-gramming.

Theon–offbuttonisusedtoturnthedeviceonandoff.

TheLCDdisplaysupportspumpoperationoptions.

Whentheoperatorchoosesbetweentwoormoreoptions,theinter-facemessageindicateswhatisbeingchosen,andtheinitialordefaultoptionisdisplayed.

Pressingtheupbuttonallowstheprogrammertoscrollthroughtheavailableoptions.

Whenanumericalvalueisrequired,theinterfacemessageconveysitsnameandthedisplayedvalueispresentedwiththecursorunderoneofthevalue'sdigits.

Theprogrammercanmovethepositionofthecursorbypressingtheleftandrightbuttons.

Heorshecanpresstheupbuttontoscrollthroughthedifferentdigitvaluesavailableatthatcursorposition.

Theclearbuttonsetsthedisplayedvaluetozero.

Theenterbuttonisusedtoconrmvaluesandtreatmentoptions.

Asidefromtheadministrationoftreatment,thepump'sautomationsupportsdynamiccheckingandrestrictionofoperatorenteredvalues.

Thus,inadditiontohavinghardlim-itsonvalueranges,theextremacanchangedynamicallyinresponsetootheruserspeciedvalues.

2.

2ApparatusAllformalmodelswereconstructedusingtheSymbolicAnalysisLaboratory(SAL)language[9]becauseofitsasso-ciatedanalysisanddebuggingtools,anditssupportforboththeasynchronousandsynchronouscompositionofdifferent123222M.

L.

Bolton,E.

J.

Bassmodels(modulesusingSAL'sinternalsemantics).

ThetaskmodelrepresentationsdescribednextweretranslatedintotheSALlanguageasasinglemoduleusingacustom-builtjavaprogram[5].

AllvericationsweredoneusingSAL-SMC3.

0,theSALsymbolicmodelchecker.

1Vericationswereconductedona3.

0GHzdual-coreIntelXeonprocessorwith16GBofRAMrunningtheUbuntu9.

04desktop.

Humantaskmodelswerecreatedusinganintermediarylanguagecalledenhancedoperatorfunctionmodel(EOFM)[4],anXML-based,generichumantaskmodelinglan-guagebasedontheoperatorfunctionmodel(OFM)[21,26].

EOFMsarehierarchicalandheterarchicalrepresentationsofgoalormissiondrivenactivitiesthatdecomposeintolowerlevelactivities,andnally,atomicactions—whereactionscanrepresentanyobservable,cognitive,orperceptualhumanbehavior.

EOFMsexpresstaskknowledgebyexplicitlyspec-ifyingtheconditionsunderwhichhumanoperatoractivi-tiescanbeundertaken:whatmustbetruebeforetheycanexecute(preconditions),whentheycanrepeat(repeatcon-ditions),andwhentheyhavecompleted(completioncondi-tions).

Anyactivitycandecomposeintooneormoreotheractivitiesoroneormoreactions.

Adecompositionoperatorspeciesthetemporalrelationshipsbetweenandthecardi-nalityofthedecomposedactivitiesoractions(whentheycanexecuterelativetoeachotherandhowmanycanexecute).

EOFMscanberepresentedvisuallyasatree-likegraphstructure(examplescanbeseeninFigs.

3,4,5,6,7).

Intheserepresentations,actionsarerepresentedasrect-anglesandactivitiesarerepresentedasroundedrectan-gles.

Anactivity'sdecompositionispresentedasanarrow,labeledwiththedecompositionoperator,extendingbelowitthatpointstoalargeroundedrectanglecontainingthedecomposedactivitiesoractions.

Inthiswork,threedecompositionoperatorsareused:(1)ord(allactivitiesoractionsinthedecompositionmustexecuteintheordertheyappear);(2)or_seq(oneormoreoftheactivitiesoractionsinthedecompositionmustexecute);and(3)xor(exactlyoneactivityoractioninthedecompositionmustexecute).

Conditionsonactivitiesarerepresentedasshapesorarrows(annotatedwiththeconditionlogic)con-nectedtotheactivitythattheyconstrain.

Theform,posi-tion,andcoloroftheshapearedeterminedbythetypeofcondition.

Apreconditionispresentedasayellow,downward-pointingtriangleconnectedtotheleftsideoftheactivity.

Acompletionconditionisrepresentedbyamagenta,upward-pointingtriangleconnectedtotherightsideoftheactivity.

Arepeatconditionisdepictedasanarrowrecur-sivelypointingtothetopoftheactivity.

Moredetailscanbefoundin[4].

1SomemodeldebuggingwasalsoconductedusingSAL'sboundedmodelchecker.

2.

3VericationspecicationTwospecicationswereemployedineachofthemodelingphases:bothwerewritteninlineartemporallogicandeval-uatedusingSAL–SMC.

Therst(Eq.

1),usedformodeldebugging,veriesthatavalidprescriptioncouldbepro-grammedintothepump:GiInterfacemessage=TreatmentAdministering∧iMode=iPrescribedMode∧lFluidVolume=iPrescribedFluidVolume∧lPCADose=iPrescribedPCADose∧lDelay=iPrescribedDelay∧lBasalRate=iPrescribedBasalRate∧l1HourLimit=iPrescribed1HourLimit∧lBolus=iPrescribedBolus∧lContinuousRate=iPrescribedContinuousRate(1)Here,ifthemodelisabletoenterastateindicatingthattreatmentisadministering(iInterfaceMessage=Treat-mentAdministering)withtheentered(orprogrammed)prescriptionvalues(iMode,lFluidVolume,…,lContinuous-Rate)matchingtheprescriptionvaluesgeneratedbythemissionmodel(variableswiththeiPrescribedprex),acounterexamplewouldbeproducedillustratinghowthatpre-scriptionwasprogrammed.

Variableswithaniprexindicatethatthevariableisaninputtothehumantaskmodel.

Vari-ableswithanlprexindicatethatthevariableislocaltoagivenmodel.

Thesecondspecication(Eq.

2)representedasafetyprop-ertythatwasexpectedtoverifytotrue,thusallowingthemodelcheckertotraversetheentirestatespaceofeachphase'smodel.

BecausesuchavericationallowsSALtoreportthesizeofamodel'sstatespace,vericationsusingthisspecicationwouldprovidesomemeansofcomparingthecomplexityofthemodelsproducedineachphase.

GiInterfaceMessage=TreatmentAdministering∧iMode=Continuous∧lDelay=0(2)Here,thespecicationisassertingthatthemodelshouldneverenterastatewheretreatmentisadministeringinthePCAorBasal+PCAmodes(iMode=Continuous)whenthereisnodelaybetweendoses.

2Thus,ifEq.

(2)veriestotrue,thepumpwillneverallowaprogrammertoenterprescriptionsthatwouldallowpatientstocontinuouslyadministerPCAdosestothemselves[2].

2AdelaycanonlybeensetwhenthePCAorBasal+PCAmodeshavebeenselectedbythehumanoperator.

TherearenodelaysbetweendoseswhenthepumpisintheContinuousmode.

123Formallyverifyinghuman–automationinteraction2233Phase1a:arepresentativemodeloftheIpump3.

1ModeldescriptionAninitialmodelwascreatedtoconformtothearchitecturalanddesignphilosophyrepresentedinFig.

2:themissionwasrepresentedasasetofviableprescriptionsoptions;themis-sion,humanoperator,human-deviceinterface,anddeviceautomationweremodeledindependentlyofeachother;andthebehavioroftheautomatedsystemandHDImodelswasdesignedtoaccuratelyreectthebehaviorofthesesystemsasdescribedintheuser'smanual[2]andobservedthroughdirectinteractionwiththedevice.

Anunconstrainedhumanoperatorwasconstructedthatcouldissueanyvalidhumanactiontothehuman-deviceinterfacemodelatanygiventime.

BecausethePCApumpgenerallyoperatesinacon-trolledenvironment,awayfromtemperatureandhumidityconditionsthatmightaffecttheperformanceofthepump'sautomation,noenvironmentalmodelwasincluded.

Finally,becausedocumentationrelatedtotheinternalworkingsofthepumpwaslimited,thesystemautomationmodelwasrestrictedtothatassociatedwiththepumpprogrammingpro-cedure:behaviorthatcouldbegleanedfromtheoperator'smanual[2],correspondenceswithhospitalstaff,anddirectinteractionwiththepump.

3.

2ModelcoordinationModelinfrastructurewasrequiredtoensurethathumanoper-atoractionswereproperlyrecognizedbytheHDImodel.

Inanidealmodelingenvironment,humanactionbehaviororig-inatingfromthehumanoperatormodelcouldhavebothanasynchronousandsynchronousrelationshipwiththeHDImodel.

SynchronousbehaviorwouldallowtheHDImodeltoreacttouseractionsinthesametransitioninwhichtheywereissued/performedbythehumanoperatormodel.

How-ever,boththehumanoperatorandHDImodelsoperateinde-pendentlyofeachother,andmayhavestatetransitionsthataredependentoninternalorexternalconditionsthatarenotdirectlyrelatedtothestateoftheothermodel.

Thissuggestsanasynchronousrelationship.

SALonlyallowsmodelstobecomposedwitheachotherasynchronouslyorsynchronously(butnotboth).

Thus,itwasnecessarytoadaptthemodelstosupportfeaturesassociatedwiththeunusedcomposition.

AsynchronouscompositionwasusedtocomposethehumanoperatorandHDImodels.

ThisnecessitatedsomeadditionalinfrastructuretopreventthehumanoperatormodelfromissuinguserinputsbeforetheHDImodelwasreadytointerpretthemandtopreventthehumanoperatormodelfromterminatingagiveninputbeforetheinterfacecouldrespondtoit.

Thiswasaccomplishedthroughtheaddi-tionoftwoBooleanvariables:oneindicatingthatinputhadbeensubmitted(henceforthcalledSubmitted)andavariableindicatingtheinterfacewasreadytoreceiveactions(hence-forthcalledReady).

Thiscoordinationoccurredasfollows:–IfReadyistrueandSubmittedisfalse,thehumanoperatormodulesetsoneormoreofthehumanactionvariablestoanewinputvalueandsetsSubmittedtotrue.

–IfReadyandSubmittedaretrue,thehuman-deviceinter-facemodulerespondstothevaluesofthehumanactionvariablesandsetsReadytofalse.

–IfReadyisnottrueandSubmittedistrue,thehumanoper-atormodulesetsSubmittedtofalse.

–IfReadyandSubmittedarebothfalseandtheautomatedsystemisreadyforadditionalhumanoperatorinput,thehuman-deviceinterfacemodulesetsReadytotrue.

3.

3VericationresultsAttemptstoverifythismodelusingthespecicationsinEqs.

1and2resultedintwoproblemsrelatedtothefeasibilityandusefulnessofthevericationprocedure.

First,theSAL–SMCprocedurefortranslatingtheSALcodeintoabinarydecisiondiagram(BDD)tookexcessivelylong(morethan24h),atimeframeimpracticalformodeldebugging.

Second,thevericationprocesswhichfollowedtheconstructionoftheBDDeventuallyranoutofmemory,thusnotreturningavericationresult.

4Phase1b:areducedBaxterIpumpmodelAsaresultofthefailedvericationofthemodelproducedinPhase1a,significantrevisionswererequiredtomakethemodelmoretractable.

Thesearediscussedbelow.

4.

1RepresentationofnumericalvaluesToreducethetimeneededtoconverttheSAL-codemodeltoaBDD,anumberofmodicationsweremadetothemodelfromPhase1abyrepresentingmodelconstructsinwaysmorereadilyprocessedbythemodelchecker.

Assuch,themod-icationsdiscussedheredidnotultimatelymaketheBDDrepresentationofthemodelsmaller,butmerelyexpediteditsconstruction.

4.

1.

1RedundantrepresentationofvaluesTwodifferentrepresentationsofthevaluesprogrammedintothepumpbytheoperatorwereusedintheHDIanddeviceautomationmodels.

BecausetheHDIrequiredthehumanoperatortoentervaluesbyscrollingthroughtheavailablevaluesforindividualdigits,anarrayofintegerdigitswasappropriatefortheHDImodel.

However,becausethesystem123224M.

L.

Bolton,E.

J.

Bassautomationwasconcernedwithdynamicallycheckinglimitsandusingenteredvaluestocomputeothervalues,anumer-icalrepresentationoftheactualvaluewasmoreconvenientfortheautomatedsystemmodel.

ThisredundancyburdenedtheBDDtranslator.

Thiswasremediedbyeliminatingthedigitarrayrepresentationsandusingfunctionstoenableactionsfromthehumantaskmodeltoincrementallychangeindividualdigitswithinavalue.

4.

1.

2RealnumbersandintegersInthemodelproducedinPhase1a,allnumericalvalueswererepresentedasrealvalueswithrestrictedranges.

Thiswasdonebecausemostuserspeciedvalueswereeitherinte-gersoroatingpointnumbers(precisetoasingledecimalpoint).

Nodataabstractionswereinitiallyconsideredbecausethenatureofthehumantask(modeledinPhase2)requiredmanipulationofvalues'individualdigits.

However,repre-sentingvaluesthiswayprovedespeciallychallengingfortheBDDtranslator.

Thus,allvaluesweremodiedsothattheycouldberepresentedasrestrictedrangeintegers.

Forintegervariablesrepresentingoatingpointnumbers,thismeantthatthemodelvaluewastentimesthevalueitrepresented.

Thisrepresentationallowedthevaluestostillbemanipulatedattheindividualdigitlevel,whilemakingthemmorereadilyinterpretablebytheBDDtranslator.

4.

1.

3VariablerangesInthePhase1amodel,theupperboundontherangeofallvalue-basedvariableswassettothetheoreticalmaximumofanyvaluethatcouldbeprogrammedintothepump:99,999.

3However,toreducetheamountofworkrequiredfortheBDDconversion,therangeofeachnumericallyvaluedvariablewasgivenaspecicupperboundthatcorrespondedtothemaximumvalueitcouldactuallyassumeinthedevice.

4.

2ModelreductionToreducethesizeofthemodel,avarietyofelementswereremoved.

InallcasesthesereductionsweremeanttoreducethenumberofstatevariablesintheHDIordeviceautoma-tionmodels(slicing),orreducetherangeofvaluesavariablecouldassume(dataabstraction).

Unfortunately,eachofthesereductionsalsoaffectedwhathumantaskscouldultimatelybemodeledandthusveriedinsubsequentmodeliterations.

Allofthefollowingreductionswereundertaken:–InthePhase1amodel,themissionmodelcouldgener-ateaprescriptionfromtheentireavailablerangeofvalidprescriptions.

Thiswaschangedsothatfewerprescription3Alllowerboundsweresetto0.

optionsweregeneratedinPhase1b'smissionmodel:thatofprogrammingaprescriptionwithacontinuousdosagewithtwooptionsforbolusdelivery(0.

0and1.

0ml)andtwocontinuousowrateoptions(1.

0and9.

0ml/h).

Whilethissignificantlyreducedthenumberofmodelstates,italsoreducedthenumberofprescriptionsthatcouldbeusedinvericationprocedures.

–InthePhase1amodel,theHDImodelwouldallowtheoperatortoselectwhatunitstousewhenenteringprescrip-tions(ml,mg,org).

OnlythemlunitoptionwasincludedinthePhase1bmodel.

Thisreducedthenumberofinter-facemessagesinthemodel,allowedfortheremovalofseveralvariables(thoserelatedtotheunitoptionselection,andsolutionconcentrationspecication),andreducedtherangesrequiredforseveralnumericalvaluesrelatedtotheprescription.

Thiseliminatedtheoptionofincludingunitselectionandconcentrationspecicationtaskbehaviorsinthemodel.

–InthePhase1amodel,boththeHDIanddeviceautomationmodelsencompassedbehaviorrelatedtothedeliveryofmedicationsolutionduringtheprimingandbolusadmin-istrationprocedures.

Duringpriming,theHDIallowstheoperatortorepeatedlyinstructthepumptoprimeuntilallairhasbeenpushedoutoftheconnectedtubing.

Duringbolusadministration,theHDIallowstheoperatortotermi-natebolusinfusionbypressingthestopbuttontwice.

ThisfunctionalitywasremovedfromthePhase1bmodels,thuseliminatinginterfacemessagestatesandnumericalvaluesindicatinghowmuchuidhadbeendeliveredinbothpro-cedures.

Thiseliminatedthepossibilityofincorporatingtaskbehaviorrelatedtopumpprimingandbolusadminis-trationinthemodel.

–ThePhase1amodelmimickedthesecurityfeaturesfoundintheoriginaldevicewhichrequiredthehumanoperatortounlockandlockthedeviceonstartupandenterasecu-ritycode.

ThisfunctionalitywasremovedfromthePhase1bmodelwhichreducedthenumberofinterfacemessagesinthemodelandremovedthenumericalvariable(witha0–999range)associatedwithenteringthesecuritycode.

Thiseliminatedthepossibilityofmodelinghumantaskbehaviorrelatedtounlockingandlockingthepumpaswellasenteringthesecuritycodeinthemodel.

–InthePhase1amodel,theinterfacemessagecouldauto-maticallytransitiontobeingblank:mimickingtheactualpump'sabilitytoblankitsscreenafterthreesecondsofoperatorinactivity.

Becausefurtheroperatorinactionwouldresultintheoriginaldeviceissuinga"leftinpro-grammingmode"alert,ablankinterfacemessagecouldautomaticallytransitiontoanalertissuance.

Thisfunction-alitywasremovedfromthePhase1bmodel,eliminatingseveralinterfacemessagesaswellasvariablesthatkepttrackofthepreviousinterfacemessage.

Thus,theoption123Formallyverifyinghuman–automationinteraction225ofmodelingoperatortaskresponsetoscreenblankingandalertswasremovedfromthemodel.

WhilethesereductionsresultedinthePhase1bmodelbeingmuchsmallerandmoremanageablethantheoriginal,theabilitytomodelsomeofthetaskbehaviorsoriginallyasso-ciatedwiththedevicehadtobesacriced.

4.

3ResultsThePhase1bmodelwasabletocompletethevericationprocedurewithEq.

(1)andproduceacounterexamplewithasearchdepthof54inapproximately5.

9h,withthemajorityofthattime(5.

4h)usedforcreatingtheBDDrepresentation[3].

4Notsurprisingly,themodelcheckerranoutofmemorywhenattemptingtoverifyEq.

(2).

5Phase1c:asimplerPCApumpmodelWhilethemodeldevelopedinPhase1bdidproduceusableresultsandhassubsequentlybeenusedinthevericationofadditionalproperties(see[5]),thispowercameattheexpenseofareductioninthescopeofthemissionmodel.

Sincethemissiondirectlyinuenceswhathumanbehaviorwillexe-cute,thislimitedthehumantaskbehaviorthatcouldulti-matelybeveriedaspartofthesystemmodel.

Further,thefactthatthePhase1bmodelwastoocomplexforEq.

(2)tobeveriedpotentiallylimitedanyfuturemodeldevelopmentthatmightaddcomplexity.

Toremedytheseshortcoming,themodelproducedinPhase1bwasfurtherreducedtoonethatencompassedtheprogrammingofthemostbasicPCApumpfunctionalitywhiletherangesofpossiblevaluesfortheremainingmissionmodelvariableswereexpandedtobemorerealistic.

5.

1ModelreductionToobtainasmallerPCAmodel,allofthefollowingwereremoved:theselectionofmodeandtheabilitytospecifyabasalrate,continuousrate,bolusdosage,anduidvolume.

Asaresult,associatedinterfacemessagesandvariableswereremovedalongwiththeabilitytomodeltheirprogrammingaspartofthehumantaskbehaviormodel.

ThisresultedinamodelthatonlyencompassedfunctionalityforprogrammingaPCAdose,programmingthedelaybetweenPCAdoses,turningthepumponandoff,andstartingandstoppingtheadministrationoftreatment:functionalitycompatiblewiththemostbasicPCApumpoperations(see[1]).

4Completedmodels,SALoutputs,andcounterexamplescanbefoundathttp://cog.

sys.

virginia.

edu/ISSE2010/.

Valuerangeswerefurtherrestrictedtoreducethesizeofthemodel.

Specifically,theupperboundontheacceptabledelaybetweenPCAdosageswaschangedfrom240to60minutes.

This,coupledwiththeotherreductions,hadtheaddedbenetofallowingthenumberofdigitsrequiredfortheprogrammingofpumpvaluestobereducedto2ratherthantheoriginal4.

ThereductionsinotherareasallowedthescopeofthedelaysandPCAdosagesgeneratedbythemissionmodeltobeexpandedtoamorerepresentativeset.

ForPCAdosages,thefullrangeofvaluesfrom0.

1to9.

9in0.

1mlincrementsweresupported.

Fordelaybetweendosages,veoptionswereavailable:delaysof10,15,30,45,and60min.

Allpumpinterfacefunctionalitywasretainedfromthepreviousmodels.

Thus,theunconstrainedhumantaskmodelwasunchangedaswasthehumantaskandHDImodels'communicationprotocol.

5.

2ResultsThePhase1cmodelranthevericationprocedureforEq.

(1)(withtheeliminatedvariablesremoved)in6swithasearchdepthof22,muchfasterthanthemodelfromPhase1b.

ThevericationofthespecicationinEq.

(2)veriedtotruein129swithasearchdepthof259and78,768,682,750visitedstates.

6Phase2:incorporatingmodelsofhumanbehaviorInthesecondphaseofmodeling,weexpandedourinstantia-tionoftheframeworkbyincorporatingarealistichumantaskbehaviormodel.

WethereforereplacedtheunconstrainedhumanoperatorinthePhase1cmodelwithahumantaskbehaviormodelderivedfrompumpdocumentation[2]andtrainingmaterials.

ThismodelutilizedtheEOFMconceptsandthusrequiredsomeadditionalinfrastructureinordertoincorporateitintotheformalsystemmodel.

Wedescribethebehaviorsthatweremodeled,howtheseweretranslatedintotheformalmodel,andreportvericationresultsforthepro-ducedsystemmodel.

6.

1HumantaskbehaviormodelingandtranslationThepump'smaterialscontainedsixhigh-levelgoaldirectedbehaviorsforperformingavarietyofpumpactivitiesrelevanttothePhase1cmodelasfollows:–Turningonthepump.

–Stoppingtheinfusionofmedication.

–Turningoffthepump.

–EnteringaprescribedvalueforPCAdosagevolumes(inmilliliter).