NYPDzhuo爱

zhuo爱 时间:2021-04-11 阅读:()

ResearchArticleViolenceandSexinTelevisionProgramsDoNotSellProductsinAdvertisementsBradJ.

BushmanInstituteforSocialResearch,DepartmentofPsychology,andDepartmentofCommunicationStudies,UniversityofMichiganABSTRACT—Adults(N5336)18to54yearsoldwatchedatelevisionprogramcontainingviolence,sex,bothviolenceandsex,ornoviolenceandsex.

Programswereshowninacomfortableroomcontainingpaddedchairsandtastysnacks.

Eachprogramcontainedthesame12ads.

Em-beddinganadinaprogramcontainingviolenceorsexreduced(a)viewers'likelihoodofrememberingthead-vertisedbrand,(b)theirinterestinbuyingthatbrand,and(c)theirlikelihoodofselectingacouponforthatbrand.

Theseeffectsoccurredformalesandfemalesofallages,regardlessofwhethertheylikedprogramscontainingvi-olenceandsex.

Theseresultsshowthatviolenceandsexintelevisionprogramsdonotsellproductsinadvertisements.

Thenumberonepriorityintelevisionisnottotransmitqualityprogrammingtoviewers,buttodeliverconsumerstoadvertisers.

—JeffSagansky,formerCBSprogrammingchief(quotedinKim,1994,p.

1434)Mostnetworkandcabletelevisioncompaniesare100%sup-portedbyadrevenue.

Advertisersarewillingtopayalotofmoneyforairtime.

Forexample,advertiserspaid$2.

3millionforasingle30-sadairingduringSuperBowlXXXVIII(Sutel,2004).

Thegoalofadvertisingistopresentgoodsorservicesinaneffectivemannersoindividualswillpurchasethem.

Televi-sionisanidealmediumtoadvertisegoodsorservicesbecausesomanypeopleownTVsets.

IntheUnitedStates,therearemoreTVsetsthantherearetoilets(AmericanPsychologicalAssociation,1993).

Televisionreachesmoreofanadvertiser'spotentialcustomersthandoesanyothermedium,andadultsspendsignificantlymoretimewithtelevisionthanwithanyothermedium(TelevisionBureauofAdvertising,2003).

Itiscommonlyassumedthattelevisedviolenceandsexsellproducts.

AlthoughTVprogramswithviolenceandsexdoat-tractyoungerviewers,overalltheyattractfewerviewersthanprogramswithoutviolenceandsex(Hamilton,1998;ParentsTelevisionCouncil,2003).

Thesmalleraudiencesizereducesthepotentialimpactofanadvertisement.

ThisimpactwouldbefurtherreducedifTVviewerscannotremembertheproductbeingadvertised.

Researchhasalreadyshownthattelevisedviolenceandseximpairmemoryforadvertisedproducts.

Ameta-analysisof16studiesinvolving2,474participantsfoundthatmemoryforadvertisedbrandswas27%lowerifadswereembeddedinaviolentprogramthanifthesameadswereem-beddedinanonviolentprogram(Bushman,2003;seealsoBushman&Phillips,2001).

Televisedsexalsomayimpairmemoryforadvertisedbrands(Bushman&Bonacci,2002).

Aplausiblecauseofthismemoryimpairmentisthatindi-vidualshavealimitedamountofattentiontodirecttowardtele-visionprograms(Lang,Newhagen,&Reeves,1996).

Researchsuggeststhatindividualspaymoreattentiontoviolentmediathantononviolentmedia(Furnham&Gunter,1987;Langetal.

,1996;Williamson,Kosmitzki,&Kibler,1995).

Individualsalsopaymoreattentiontosexualmediathantononsexualmedia(e.

g.

,Geer,Judice,&Jackson,1994;Geer&McGlone,1990).

Fromanevolutionaryperspective,thismakessense.

Ouran-cestorswhopaidattentiontoviolentandsexualcuesweremorelikelytosurviveandpassontheirgenesthanwerethosewhoignoredviolentandsexualcues.

Themoreattentionviewerspaytosexualorviolentprograms,thelessattentiontheyhaveavailableforthecommercialsembeddedinthoseprograms.

Eventhoughcommercialsoccurduringbreaksinaprogram,viewersmaystillbedevotingcognitiveresourcestothinkingabouttheprogramthatattractedtheirattentionsostrongly.

Thepresentstudyprovidesanimportantextensionoverpre-viousstudiesbecauseittestedwhethertelevisedviolenceandsexalsoinuencebuyingintentionsandconsumerbehaviors.

Thisresearchisimportantfortheoreticalandpracticalreasons.

AddresscorrespondencetoBradJ.

Bushman,InstituteforSocialResearch,426ThompsonSt.

,AnnArbor,MI48106;e-mail:bbushman@umich.

edu.

PSYCHOLOGICALSCIENCE702Volume16—Number9Copyrightr2005AmericanPsychologicalSocietyInthetheoryofreasonedaction,behavioralintentionsareviewedasanimportantmediatorofbehavior(e.

g.

,Ajzen&Fishbein,1977).

Thepresentstudyincludedameasureofbuyingintentions,whicharerelatedtoconsumerbehaviors(e.

g.

,Bagozzi,Baumgartner,&Yi,1991,1992;Shimp&Kavas,1984).

Specifically,thisstudytestedwhetherbuyingintentionsme-diatetheeffectofviolenceandsexinaTVprogramonthechoiceofacouponforanadvertisedproduct.

In2000,morethan77%ofAmericansusedcoupons,whichsavedthemmorethan$3.

6billion(CouponUsageStatistics,2000).

Ofcourse,thevalueofthegoodstheypurchasedwasmuchgreaterthanthefacevalueofthecouponstheyused.

Althoughcouponchoicesarenottechnicallyconsumerbehaviors(i.

e.

,theconsumerhastore-deemthecoupon),numerousstudieshaveshownthatcouponsincreaseproductsales(e.

g.

,Ailawadi,Lehmann,&Neslin,2001;Bawa&Shoemaker,1989;Lam,Vandenbosch,Hulland,&Pearce,2001;Schindler,1992).

Couponredeemersarealsoover7timesmorelikelytomakerepeatpurchasesthanarenonredeemers(Taylor,2001).

Insummary,thepresentstudytestedwhethertelevisedvio-lenceandsexreducememoryforanadvertisedproduct,in-tentionstobuythatproduct,andthelikelihoodofchoosingacouponforthatproduct.

Italsotestedwhethermemoryforbrandsisrelatedtobuyingintentionsandcouponchoices.

Televisedviolenceandsexwereexpectedtohaveanindirecteffectoncouponchoices,withbrandmemoryandbuyingin-tentionsservingasimportantmediators.

METHODParticipantsParticipantswere336adults18to54yearsold.

Theiragedis-tributionwasrepresentativeoftheagedistributionof18-to54-year-oldU.

S.

adultswholiveinhouseholdswithTV(i.

e.

,17%ages18–24,12%ages25–29,14%ages30–34,15%ages35–39,16%ages40–44,14%ages45–49,and13%ages50–54;NielsenMediaResearch,2000).

Theseagegroupsarethemostimportanttoadvertisers(Hamilton,1988).

ParticipantswererecruitedusingnewspaperadvertisementsincentralIowa(e.

g.

,DesMoines,Ames).

TheywerewarnedthatsomeoftheTVprogramscontainedviolenceandsex.

Partici-pantsreceived$20inexchangefortheirvoluntaryparticipation.

ProcedureParticipantsweretestedinsmallgroups,buteachworkedin-dependently.

TheyweretoldthattheresearcherswerestudyingattitudestowardTVprograms.

Thesessionswereconductedinacomfortablesetting.

Participantswereseatedinpaddedchairsandweregivensoftdrinksandsnacks(e.

g.

,potatochips,pret-zels,cookies).

Aftergivingtheirinformedconsent,participantswereran-domlyassignedtowatchaTVprogramthatcontainedviolence,sex,violenceandsex,ornoviolenceandsex.

Therewere84participants(42men,42women)ineachofthefourgroups.

Sothatthefourtypesofprogramswouldbeadequatelysampled,sixexemplarsofeachwereused(Wells&Windschitl,1999).

Adiewasrolledtodeterminewhatprogramtoshow.

Thesixviolentprogramswere''24,''''Cops,''''ProtectandServe,''''TerrorontheJob,''''TourofDuty,''and''X-Files.

''Alloftheseprogramshadaviolent(V)contentcode;nonehadasex(S)contentcode.

Thesixsexuallyexplicitprogramswere''AllyMcBeal,''''HowardStern,''''ManShow,''''SexintheCity,''''WildonE,''and''WillandGrace.

''Alloftheseprogramshadasex(S)contentcode;nonehadaviolent(V)contentcode.

Thesixviolentandsexualprogramswere''Angel,''''BuffytheVampireSlayer,''''CSIMi-ami,''''NYPDBlue,''''SouthPark,''and''WorldWrestlingEn-tertainmentRAW.

''Alloftheseprogramshadviolent(V)andsex(S)contentcodes.

Thesixneutralprogramswere''ADatingStory,''''America'sFunniestAnimals,''''HollywoodBeyondtheStars,''''It'saMiracle,''''MiraclePets,''and''TradingSpaces.

''Noneoftheseprogramshadviolent(V)orsex(S)contentcodes.

AlloftheprogramscontainingviolenceorsexwereratedTV-14(ParentsStronglyCautioned).

AlloftheneutralprogramswereratedTV-G(GeneralAudience).

Theadsoriginallyembeddedintheprogramswereeditedout,andthesame12(30-s)adswereembeddedineachprogram.

Becauseconsumersarequiteloyaltobrands(e.

g.

,Chaudhuri,2001),weusedadsforrelativelyunfamiliarbrands(i.

e.

,BodyFantasies,Dermoplast,FerraroRaffaelloChocolates,JoseOle,LibmanNittyGrittyRollerMop,Mederma,NatraTaste,NewSkin,NutraNails,Proheart6,SenokotNaturalVegetableLaxative,andSuddenChangeUndereyeLift).

Therewerethreecommercialbreaksatap-proximately12min,24min,and36minintoeachprogram.

Fouradswerepresentedineachbreak.

Tworandomordersofadswereused.

ImmediatelyafterviewingtheTVprogram,participantsratedhowexciting,boring,involving,humorous,violent,andsexuallyarousingtheythoughtitwas,usingascalerangingfrom1(notatall)to10(extremely).

Theviolenceandsexualarousalratingswereusedasmanipulationchecksfortheprogramcontentcodes.

TheotherratingswereusedascovariatestocontrolfordifferencesamongTVprogramsotherthandifferencesinviolentandsexualcontent.

AfterratingtheTVprogram,participantsreceivedsur-prisememorytests.

First,theylistedasmanybrandnamesastheycouldrecall.

Second,theyreceivedalistofproducts.

Foreachtypeofproduct(e.

g.

,sugarsubstitute),fourbrandswerelisted—theadvertisedbrand(e.

g.

,NatraTaste)andthreefoilbrands(e.

g.

,SugarTwin,SweetDeal,Sweet'n'Smart).

Aswiththeactualbrands,foilbrandsthatwouldberelativelyunfamiliartomostparticipantswereselected.

Foreachkindofproduct,participantscircledthebrandthatwasadvertised.

Volume16—Number9703BradJ.

BushmanNext,participantsreportedtheirbuyingintentionsusingthesamelist.

Foreachtypeofproduct,theycircledthebrandthey''wouldbemostlikelytobuy.

''Thenumberofcouponsselectedforadvertisedproductswasusedasameasureofconsumerbehavior.

Couponsforall40brandsonthelistwereavailable,andparticipantscouldchoose10.

Becauseinadequatefacevaluesoncouponscanreducetheireffectiveness(Chakraborty&Cole,1991;Cheong,2003),allofthecouponsofferedparticipants$1offthelistedprice—asub-stantialsavingsfortheproductsusedinthisstudy,andabout30centshigherthantheaveragecouponfacevalue(PromotionMarketingAssociation,2000).

Professionallyprinted(bogus)couponswereavailablefortheadvertisedandfoilbrands.

Next,participantsreportedtheirdemographics(i.

e.

,age,gender,ethnicbackground)andtheirtelevisionviewinghabits(i.

e.

,thenumberofhourseachweektheyspentwatchingTVandthepercentageoftimetheyspentwatchingviolentandsexualprograms).

Thelattermeasureswereusedtocontrolforhabitualexposuretotelevisedviolenceandsex.

Participantsalsore-portediftheyhadseentheassignedprogrambefore(thatepi-sodeoranyepisodes),iftheyhadseenanyoftheadsbefore,andiftheyhadheardofanyoftheadvertisedproductsbefore.

TheseresponseswereusedtocontrolforpreviousexposuretotheTVprogramsandads.

Finally,participantswerefullydebriefed.

Becausethecouponswerebogus,wegaveparticipantsthefacevalueofthecouponsinstead(i.

e.

,$10).

Thus,eachparticipantreceived$30($20forparticipatinginthestudyand$10fortheboguscoupons).

RESULTSPreliminaryAnalysesandManipulationChecksViolenceRatingsTypeofTVprogramhadasignificanteffectonviolenceratings,F(3,332)5173.

56,p.

05.

Thus,thedatawerecollapsedacrossexemplarsofprogramtypesforsubsequentanalyses.

DemographicDataThedemographicvariables(i.

e.

,sex,age,ethnicbackground)hadnomaineffectsonanyoftheoutcomemeasuresandwereTABLE1MeanViolenceandSexRatings,Memory,BuyingIntentions,andConsumerBehaviorsintheFourConditionsVariableConditionNeutralViolenceSexViolenceandsexViolencerating(1–10)1.

31b(0.

20)6.

12a(0.

20)1.

61b(0.

20)5.

82a(0.

20)Sexrating(1–10)1.

05b(0.

15)1.

43b(0.

15)3.

60a(0.

15)3.

42a(0.

15)NumberofbrandsrecalledAdjusted1.

21a(0.

12)0.

91ab(0.

12)0.

52c(0.

12)0.

72bc(0.

12)Unadjusted1.

18a(0.

12)0.

95ab(0.

12)0.

52c(0.

12)0.

70bc(0.

12)NumberofbrandsrecognizedAdjusted5.

76a(0.

27)4.

36b(0.

28)3.

54c(0.

28)3.

58c(0.

27)Unadjusted5.

70a(0.

28)4.

61b(0.

28)3.

44c(0.

28)3.

50c(0.

28)BuyingintentionsAdjusted5.

61a(0.

26)4.

15b(0.

26)4.

13b(0.

26)4.

16b(0.

26)Unadjusted5.

48a(0.

26)4.

23b(0.

26)4.

23b(0.

26)4.

13b(0.

26)CouponchoicesAdjusted5.

75a(0.

36)4.

31b(0.

37)4.

54b(0.

36)4.

10b(0.

36)Unadjusted5.

50a(0.

36)4.

41b(0.

36)4.

74ab(0.

36)4.

05b(0.

36)Note.

Standarderrorsareinparentheses.

AdjustedmeanswereadjustedforwhetherparticipantshadseentheTVprogram(theepisodeshownaswellasotherepisodes);whethertheyhadseentheadsbefore;whethertheywerefamiliarwiththeproductsadvertised;howexciting,boring,humorous,andinvolvingtheyratedtheTVprogram;howmanyhourstheyspentwatchingTVperweek;andthepercentageoftimetheyspentwatchingtelevisedsexandviolence.

Unadjustedmeanswerenotadjustedforanycovariates.

''Buyingintentions''referstothenumberofadvertisedproductsparticipantsintendedtobuy,and''couponchoices''referstothenumberofadvertisedproductswhosecouponswerechosen.

Withinarow,meanssharingthesamesubscriptarenotsignificantlydifferentatthe.

05significancelevel.

704Volume16—Number9ViolenceandSexDon'tSellnotinvolvedinanysignificantinteractions,ps>.

05.

Thus,thedatawerecollapsedacrossdemographicgroupsforsubsequentanalyses.

RandomOrdersofAdsTwodifferentrandomordersofadswereused.

Becauseran-domizationorderdidnotaffectanyoftheoutcomemeasures(ps>.

05),thedatawerecollapsedacrossthetwoordersofads.

FamiliarityWithAdsandBrandsAsexpected,mostparticipantshadnotseentheadsbeforeandwerenotfamiliarwiththeadvertisedbrands(meannumberofadsseenbefore51.

61,SE50.

13;meannumberoffamiliarbrands51.

93,SE50.

15).

PrimaryAnalysesAnalysisofcovariance(ANCOVA)wasusedtotesttheeffectsoftelevisedviolenceandsexontheoutcomemeasures.

CovariatesincludedwhetherparticipantshadseentheTVprogram(theepisodeshownaswellasotherepisodes);whethertheyhadseentheadsbefore;whethertheywerefamiliarwiththeadvertisedbrands;howexciting,boring,humorous,andinvolvingtheyratedtheTVprogram;howmanyhourstheyspentwatchingTVperweek;andthepercentageoftimetheyspentwatchingtele-visedviolenceandsex.

Theresults,however,weresimilarwhennocovariateswereincludedintheanalyses(seeTable1).

IfasignificanteffectwasfoundfortypeofTVprogram,aplannedcontrastwasperformedtotestwhetherparticipantswhosawaprogramwithoutviolenceandsexrespondeddifferentlyfromparticipantswhosawaprogramwithviolenceorsex.

Onthebasisofpreviousresearch,nodifferencesbetweenviolentandsexualprogrammingwerepredicted(Bushman&Bonacci,2002).

Thus,therespectivecontrastweightsfortheneutral,violent,sexual,andviolentsexualprogramswere3,11,11,and11.

Posthocttestswerealsoconductedtoexplorepossiblediffer-encesbetweenviolentandsexualprogramming(seeTable1).

CouponChoicesTypeofTVprogramsignificantlyinuencedwhetherpartici-pantsselectedcouponsforadvertisedbrands,F(3,320)54.

16,p<.

007(seeTable1).

Participantswhowatchedaprogramwithoutviolenceandsexselected33%morecouponsforadvertisedbrandsthandidparticipantswhowatchedaprogramwithviolenceorsex,F(1,320)511.

05,p<.

001,rpb5.

14.

1Posthoccomparisonsshowedsimilareffectsforviolentandsexualprogrammingoncouponchoices(seeTable1).

Onlyonecovariatewassignificant.

Themoretelevisionparticipantswatched,themorelikelytheyweretochoosecouponsforadvertisedbrands,F(1,320)54.

20,p<.

05,r5.

16.

BuyingIntentionsForeachtypeofproduct,participantsindicatedthebrandtheyweremostlikelytobuy.

TypeofTVprogramsignificantlyin-uencedbuyingintentions,F(3,320)58.

00,p<.

0001(seeTable1).

Participantswhowatchedaprogramwithoutviolenceandsexselected35%moreoftheadvertisedbrandsthandidparticipantswhowatchedaprogramwithviolenceorsex,F(1,320)523.

35,p<.

0001,rpb5.

23.

Posthoccomparisonsshowedsimilareffectsforviolentandsexualprogrammingonbuyingintentions(seeTable1).

Noneofthecovariatesweresignificant.

RecallTypeofTVprogramsignificantlyinuencedbrandrecall,F(3,320)56.

51,p<.

0003(seeTable1).

Brandrecallwas68%higherforpeoplewhosawaprogramwithoutviolenceandsexthanforpeoplewhosawaprogramwithviolenceorsex,F(1,320)513.

98,p<.

0002,rpb5.

18.

Therecallimpairmenttendedtobelargerforsexualprogrammingthanforviolentprogramming(seeTable1).

Onlyonecovariatewassignificant.

Brandrecallwaspositivelycorrelatedwiththenumberofad-vertisedproductsparticipantswerefamiliarwith,F(1,320)56.

94,p<.

009,r5.

27.

RecognitionTypeofTVprogramsignificantlyinuencedbrandrecognition,F(3,320)514.

25,p<.

0001(seeTable1).

Brandrecognitionwas51%higherforparticipantswhosawaprogramwithoutviolenceandsexthanforparticipantswhosawaprogramwithviolenceorsex,F(1,320)536.

62,p<.

0001,rpb5.

29.

Therecognitionimpairmenttendedtobelargerforsexualpro-grammingthanforviolentprogramming(seeTable1).

Brandrecognitionwasalsopositivelycorrelatedwiththenumberofproductsparticipantswerefamiliarwith,F(1,320)513.

71,p<.

0003,r5.

31.

TheRoleofMemoryandBuyingIntentionsinCouponChoicesStructuralequationmodelswerecomputedwithAMOSusingmaximumlikelihoodestimation(Arbuckle,1999).

Thehy-pothesizedmodelwasthatbrandmemoryandbuyingintentionsmediatetheeffectofTVviolenceandsexoncouponchoices.

Inspecifyingthemodel,adummyvariablewasusedtorepresentTVviolenceandsex(violentorsexualprogram51,neutralprogram50).

Brandmemorywastreatedasalatentvariable,measuredusingbrandrecallandrecognition.

Thevariance-covariancematrixusedfortheanalysesisgiveninTable2.

Thehypothesizedmediationmodeltthedataextremelywell,w2(5,N5336)54.

76,p<.

45,GFI(goodness-of-tindex)5.

995,1ThecomparativepercentagesreportedhereandlaterinResultswerecal-culatedbysummingthevaluesfortheparticipantswhowatchedviolentpro-gramming,sexualprogramming,andviolentsexualprogramming;dividingby3;andthendividingtheresultintothevaluefortheparticipantswhowatchedneutralprogramming:neutral/[(violence1sex1violenceandsex)/3].

Forex-ample,usingthedatainTable1,onecanseethatthenumberofadvertisedbrandswhosecouponswerechosenwas33%higherforparticipantswhosawaneutralprogramthanfortheothergroups:5.

75/[(4.

3114.

5414.

10)/3]51.

33,or33%higher.

Volume16—Number9705BradJ.

BushmanCFI(comparativetindex)51,RMSEA(rootmeansquareerrorofapproximation)5.

005.

AscanbeseeninFigure1,TVvio-lenceandseximpairedbrandmemory.

Brandmemoryandbuyingintentionswereimportantmediators.

Peopleintendedtobuybrandstheycouldremember,andtheychosecouponsforbrandstheyintendedtobuy.

AnalternativemodelincludeddirectpathsfromTVviolenceandsextobuyingintentionsandtocouponchoice.

Becausethemediationmodelisnestedwithinthisalternativemodel,achi-squaredifferencetestcanbeusedtocomparethetwomodels.

Thedifferencetestwasnonsignificant,w2(3,N5336)53.

68,p<.

30.

Thus,TVviolenceandsexdidnothaveadirecteffectonbuyingintentionsorcouponchoice.

TheeffectsofTVviolenceandsexoncouponchoicewereindirect,throughbrandmemoryandbuyingintentions.

Similaranalyseswereperformedtotesttheseparateeffectsofviolenceandsexonbrandmemory,buyingintentions,andcouponchoices.

TheseanalysesfoundsimilareffectsforTVviolenceandsex(seetheappendix).

DISCUSSIONItiscommonlyassumedthatviolenceandsexsellproducts,buttheymightactuallyhavetheoppositeeffect.

Thepresentstudyreplicatespreviousstudiesshowingthattelevisedviolenceandseximpairmemoryforadvertisedproducts.

Becausetelevisedviolenceandsexhadsimilareffectsonrecallandrecognition,thememoryfailureisprobablyduetoencodingratherthanre-trieval.

Televisedviolenceandsexalsodecreasedintentionstobuytheadvertisedbrandsandreducedthenumberofadver-tisedbrandswhosecouponsparticipantschose.

Memoryisanimportantoutcomemeasure,becauseitispositivelyrelatedtobuyingintentionsandcouponchoices.

Itistruethatviolentandsexyprogramsattractyoungviewers,andthisagegroupishighlydesirabletoadvertisers.

However,theeffectsinthepresentresearchheldformenandwomenofallages,regardlessofwhethertheylikedtowatchviolentorsexualprograms.

Theobtainedresultsareconsistentwiththetheoryofreasonedaction(e.

g.

,Ajzen&Fishbein,1977),whichpositsthatbe-havioralintentionsmediatetheeffectofapersuasivemessageonbehavior.

Inthepresentstudy,buyingintentionsmediatedtheeffectoftelevisedviolenceandsexoncouponchoices.

Thepresentstudyhasimportantpracticalimplicationsforsociety.

IfadvertisersrefusedtosponsorviolentandsexualTVprograms,suchprogramswouldbecomeextinct.

About60%ofTVprogramscontainviolenceorsex(Kunkeletal.

,1999;Na-tionalTelevisionViolenceStudy,1998).

TVviolenceandsexcanhaveanegativeimpactonsociety.

Researchfromhundredsofstudiesconductedoverseveraldecadeshasshownthattele-visedviolenceincreasessocietalviolence(e.

g.

,Anderson&Bushman,2002).

Sexuallyexplicitmediapromotesexualcal-lousness,cynicalattitudesaboutloveandmarriage,andper-ceptionsthatpromiscuityisthenorm(e.

g.

,Allen,Emmers,&Gebhardt,1995;Zillmann,2000).

Moreover,mediainwhichsexiscombinedwithviolencemayhaveparticularlyperniciouseffects(e.

g.

,Allen,D'Alessio,&Brezgel,1995;Linz,Donner-TABLE2Variance-CovarianceMatrixfortheStructuralEquationAnalysesMeasure123451.

TVviolenceorsex0.

18(0.

750).

18n.

29n.

23n.

14n2.

Brandrecall0.

0851.

174(0.

839).

58n.

33n.

18n3.

Brandrecognition0.

3491.

7377.

618(4.

313).

51n.

21n4.

Buyingintentions0.

2410.

8563.

3885.

833(4.

515).

37n5.

Consumerbehavior0.

2070.

6551.

9882.

95911.

229(4.

676)Note.

N5336.

Variancesandmeans(inparentheses)areonthediagonal;covariancesarebelowthediagonal.

Fordescriptivepurposes,correlationsareabovethediagonal.

np<.

05.

Fig.

1.

Effectoftelevisionviolenceandsexonviewers'consumerbehavior(i.

e.

,choosingcouponsforadvertisedbrands).

Theanalysisdepictedheretestedbrandmemoryandbuyingintentionsasmediatorsoftheeffect.

Asterisksindicatesignificantpathcoefcients,np<.

05.

Standardizedestimatesareshown.

706Volume16—Number9ViolenceandSexDon'tSellstein,&Penrod,1988).

Thus,sponsoringviolentandsexualprogramsmightbebadforsocietyandbadforbusiness.

Acknowledgments—ThisresearchwasfundedinpartbyaresearchgrantfromIowaStateUniversity.

IwouldliketothankRebeccaMarzenandLauraValenzianofortheirhelprecordingtheprograms,NicoleOswaltforherhelptestingparticipants,andMikeGillespieforhishelpwiththestructuralequationanalyses.

IalsowouldliketothankRowellHuesmannforhishelpfulfeedbackonadraftofthismanuscript.

REFERENCESAilawadi,K.

L.

,Lehmann,D.

R.

,&Neslin,S.

A.

(2001).

Marketresponsetoamajorpolicychangeinthemarketingmix:LearningfromProcter&Gamble'svaluepricingstrategy.

JournalofMarketing,65,44–61.

Ajzen,I.

,&Fishbein,M.

(1977).

Attitude-behaviorrelations:Atheo-reticalanalysisandreviewofempiricalresearch.

PsychologicalBulletin,84,888–914.

Allen,M.

,D'Alessio,D.

,&Brezgel,K.

A.

(1995).

Ameta-analysissummarizingtheeffectsofpornography:II.

Aggressionafterex-posure.

HumanCommunicationResearch,22,258–283.

Allen,M.

,Emmers,T.

,&Gebhardt,L.

(1995).

Exposuretopornographyandacceptanceoftherapemyths.

JournalofCommunication,45,5–26.

AmericanPsychologicalAssociation.

(1993).

Violenceandyouth:Psychology'sresponse.

Washington,DC:Author.

Anderson,C.

A.

,&Bushman,B.

J.

(2002).

Mediaviolenceandsocietalviolence.

Science,295,2377–2378.

Arbuckle,J.

L.

(1999).

AMOS(Version4.

01)[Computersoftware].

Chicago:SmallWatersCorp.

Bagozzi,R.

P.

,Baumgartner,H.

,&Yi,Y.

(1991).

Couponusageandthetheoryofreasonedaction.

AdvancesinConsumerResearch,8,24–27.

Bagozzi,R.

P.

,Baumgartner,H.

,&Yi,Y.

(1992).

Stateversusactionorientationandthetheoryofreasonedaction:Anapplicationtocouponusage.

JournalofConsumerResearch,18,505–518.

Bawa,K.

,&Shoemaker,R.

(1989).

Analyzingincrementalsalesfromadirectmailcouponpromotion.

JournalofMarketing,53,66–78.

Bushman,B.

J.

(2003,August).

Ifthetelevisionprogrambleeds,memoryfortheadvertisementrecedes.

PaperpresentedattheannualmeetingoftheAmericanPsychologicalAssociation,Toronto,Ontario,Canada.

Bushman,B.

J.

,&Bonacci,A.

M.

(2002).

Violenceandseximpairmemoryfortelevisionads.

JournalofAppliedPsychology,87,557–564.

Bushman,B.

J.

,&Phillips,C.

M.

(2001).

Ifthetelevisionprogrambleeds,memoryfortheadvertisementrecedes.

CurrentDirectionsinPsychologicalScience,10,44–47.

Chakraborty,G.

,&Cole,C.

(1991).

Theeffectsofcouponcharacter-isticsonbrandchoice:Alaboratorystudy.

PsychologyandMar-keting,8,145–159.

Chaudhuri,A.

(2001).

Thechainofeffectsfrombrandtrustandbrandaffecttobrandperformance:Theroleofbrandloyalty.

JournalofMarketing,65,81–93.

Cheong,K.

J.

(2003).

Observations:Arecents-offcouponseffectiveJournalofAdvertisingResearch,33,73–78.

Furnham,A.

,&Gunter,B.

(1987).

Effectsoftimeofdayandmediumofpresentationonimmediaterecallofviolentandnonviolentnews.

AppliedCognitivePsychology,1,255–262.

Geer,J.

H.

,Judice,S.

,&Jackson,S.

(1994).

Readingtimesforeroticmaterial:Thepausetoreect.

TheJournalofGeneralPsychology,121,345–352.

Geer,J.

H.

,&McGlone,M.

S.

(1990).

Sexdifferencesinmemoryforerotica.

CognitionandEmotion,4,71–78.

Hamilton,J.

T.

(1998).

Channelingviolence:Theeconomicmarketforviolenttelevisionprogramming.

Princeton,NJ:PrincetonUniver-sityPress.

Kim,S.

J.

(1994).

''Viewerdiscretionisadvised'':Astructuralapproachtotheissueoftelevisionviolence.

UniversityofPennsylvaniaLawReview,142,1383–1441.

Kunkel,D.

,Cope,K.

M.

,MaynardFarinola,W.

J.

,Biely,E.

,Rollin,E.

,&Donnerstein,E.

(1999).

SexonTV.

MenloPark,CA:KaiserFamilyFoundation.

Lam,S.

Y.

,Vandenbosch,M.

,Hulland,J.

,&Pearce,M.

(2001).

Eval-uatingpromotionsinshoppingenvironments:Decomposingsalesresponseintoattraction,conversion,andspendingeffects.

Mar-ketingScience,20,194–215.

Lang,A.

,Newhagen,J.

,&Reeves,B.

(1996).

Negativevideoasstructure:Emotion,attention,capacity,andmemory.

JournalofBroadcastingandElectronicMedia,40,460–477.

Linz,D.

G.

,Donnerstein,E.

,&Penrod,S.

(1988).

Effectsoflong-termexposuretoviolentandsexuallydegradingdepictionsofwomen.

JournalofPersonalityandSocialPsychology,55,758–768.

NationalTelevisionViolenceStudy.

(1998).

NationalTelevisionVio-lenceStudy(Vol.

3).

SantaBarbara:UniversityofCalifornia,SantaBarbara,CenterforCommunicationandSocialPolicy.

NielsenMediaResearch.

(2000).

Nielsentelevisionindex,nationalaudiencedemographics(Vol.

1).

NewYork:Author.

ParentsTelevisionCouncil.

(2003).

Sexlosesitsappeal:AstateoftheindustryreportonsexonTV.

RetrievedDecember15,2003,fromhttp://www.

parentstv.

org/ptc/publications/reports/stateindustrysex/main.

aspPromotionMarketingAssociation.

(2000).

Couponusagestatistics.

RetrievedJuly21,2004,fromhttp://couponing.

about.

com/cs/aboutcouponing/a/couponusage2000.

htmSchindler,R.

M.

(1992).

Acouponismorethanalowprice:Evidencefromashopping-simulationstudy.

PsychologyandMarketing,9,431–451.

Shimp,T.

A.

,&Kavas,A.

(1984).

Thetheoryofreasonedactionappliedtocouponusage.

JournalofConsumerResearch,11,795–809.

Sutel,S.

(2004).

NewcropofoddSuperBowladstodebut.

RetrievedJune2005fromAPOnline:http://newslink.

nandomedia.

com/SportServer/football/n/playoffs/v-fresno/story/1127283p-7844151c.

htmlTaylor,G.

A.

(2001).

Couponresponseinservices.

JournalofRetailing,77,139–151.

TelevisionBureauofAdvertising.

(2003).

MediacomparisonstudybytheTelevisionBureauofAdvertising.

(AvailablefromtheTelevisionBureauofAdvertising,3East54thStreet,NewYork,NY10022-3108)Wells,G.

L.

,&Windschitl,P.

D.

(1999).

Stimulussamplingandsocialpsychologicalexperimentation.

PersonalityandSocialPsycholo-gyBulletin,25,1115–1125.

Williamson,S.

S.

,Kosmitzki,C.

,&Kibler,J.

L.

(1995).

Theeffectsofviewingviolenceonattentioninwomen.

TheJournalofPsychol-ogy,129,717–721.

Volume16—Number9707BradJ.

BushmanZillmann,D.

(2000).

Inuenceofunrestrainedaccesstoeroticaonadolescents'andyoungadults'dispositionstowardsexuality.

JournalofAdolescentHealth,27S,41–44.

(RECEIVED2/2/04;REVISIONACCEPTED3/29/05;FINALMATERIALSRECEIVED4/6/05)APPENDIX:SEPARATEEFFECTSOFTVVIOLENCEANDSEXIntheanalysisoftheseparateeffectsofviolentprogramming,adummyvariablewasusedtorepresentTVviolence(violentprogram51,neutralprogram50).

Thehypothesizedmedia-tionmodeltthedataextremelywell,w2(5,N5168)55.

27,p<.

49,GFI5.

988,CFI5.

998,RMSEA5.

018.

Thedirect-effectsmodeldidnotimprovethet,w2(2,N5168)50.

76,p<.

69.

Similarly,intheanalysisoftheseparateeffectsofsexualprogramming,adummyvariablewasusedtorepresentTVsex(sexualprogram51,neutralprogram50).

Thehypothesizedmediationmodeltthedataextremelywell,w2(5,N5168)56.

67,p<.

25,GFI5.

985,CFI5.

991,RMSEA5.

045.

Thedirect-effectsmodeldidnotimprovethet,w2(2,N5168)51.

00,p<.

61.

Similarresultswereobtainedfortheeffectsofprogrammingthatwasbothviolentandsexual.

AdummyvariablewasusedtorepresentTVviolenceandsex(violentandsexualprogram51,neutralprogram50).

Thehypothesizedmediationmodeltthedataextremelywell,w2(5,N5168)53.

61,p<.

61,GFI5.

992,CFI51,RMSEA50.

Thedirect-effectsmodeldidnotimprovethet,w2(2,N5168)50.

76,p<.

68.

Twoadditionalmediationmodelscompareddifferencesbetweenviolentandsexualprogramming.

Forthesemodels,scoresforbrandrecallandbrandrecognitionwerestandardizedandsummedtocreateacompositevariableforbrandmemory.

Thedirect-effectsmodelshad0degreesoffreedom(i.

e.

,satu-ratedmodels)andarenotpresentedherebecausetheyshouldnotbeinterpreted.

Onemodelcomparedprogramswithviolenceandsextoprogramswithonlyviolence.

AdummyvariablewasusedtorepresentTVsex(violentandsexualprogram51,violentprogram50).

Thehypothesizedmediationmodeltthedatawell,w2(3,N5168)53.

39,p<.

34,GFI5.

99,CFI5.

99,RMSEA5.

028.

However,thestandardizedre-gressioncoefcientforthepathbetweentheindicatorvariableandthememoryvariablewasnonsignificant(coefcient5.

07,p5.

853).

Thus,sexdidnotaddanythingabovetheeffectofviolence.

Theothermodelcomparedprogramswithviolenceandsextoprogramswithonlysex.

AdummyvariablewasusedtorepresentTVviolence(violentandsexualprogram51,sexualprogram50).

Thehypothesizedmediationmodeltthedatawell,w2(3,N5168)51.

20,p<.

75,GFI5.

996,CFI51,RMSEA50.

However,thestandardizedregressioncoefcientforthepathbetweentheindicatorvariableandthememoryvariablewasnonsignificant(coefcient5.

17,p5.

814).

Thus,violencedidnotaddanythingabovetheeffectofsex.

708Volume16—Number9ViolenceandSexDon'tSell

BushmanInstituteforSocialResearch,DepartmentofPsychology,andDepartmentofCommunicationStudies,UniversityofMichiganABSTRACT—Adults(N5336)18to54yearsoldwatchedatelevisionprogramcontainingviolence,sex,bothviolenceandsex,ornoviolenceandsex.

Programswereshowninacomfortableroomcontainingpaddedchairsandtastysnacks.

Eachprogramcontainedthesame12ads.

Em-beddinganadinaprogramcontainingviolenceorsexreduced(a)viewers'likelihoodofrememberingthead-vertisedbrand,(b)theirinterestinbuyingthatbrand,and(c)theirlikelihoodofselectingacouponforthatbrand.

Theseeffectsoccurredformalesandfemalesofallages,regardlessofwhethertheylikedprogramscontainingvi-olenceandsex.

Theseresultsshowthatviolenceandsexintelevisionprogramsdonotsellproductsinadvertisements.

Thenumberonepriorityintelevisionisnottotransmitqualityprogrammingtoviewers,buttodeliverconsumerstoadvertisers.

—JeffSagansky,formerCBSprogrammingchief(quotedinKim,1994,p.

1434)Mostnetworkandcabletelevisioncompaniesare100%sup-portedbyadrevenue.

Advertisersarewillingtopayalotofmoneyforairtime.

Forexample,advertiserspaid$2.

3millionforasingle30-sadairingduringSuperBowlXXXVIII(Sutel,2004).

Thegoalofadvertisingistopresentgoodsorservicesinaneffectivemannersoindividualswillpurchasethem.

Televi-sionisanidealmediumtoadvertisegoodsorservicesbecausesomanypeopleownTVsets.

IntheUnitedStates,therearemoreTVsetsthantherearetoilets(AmericanPsychologicalAssociation,1993).

Televisionreachesmoreofanadvertiser'spotentialcustomersthandoesanyothermedium,andadultsspendsignificantlymoretimewithtelevisionthanwithanyothermedium(TelevisionBureauofAdvertising,2003).

Itiscommonlyassumedthattelevisedviolenceandsexsellproducts.

AlthoughTVprogramswithviolenceandsexdoat-tractyoungerviewers,overalltheyattractfewerviewersthanprogramswithoutviolenceandsex(Hamilton,1998;ParentsTelevisionCouncil,2003).

Thesmalleraudiencesizereducesthepotentialimpactofanadvertisement.

ThisimpactwouldbefurtherreducedifTVviewerscannotremembertheproductbeingadvertised.

Researchhasalreadyshownthattelevisedviolenceandseximpairmemoryforadvertisedproducts.

Ameta-analysisof16studiesinvolving2,474participantsfoundthatmemoryforadvertisedbrandswas27%lowerifadswereembeddedinaviolentprogramthanifthesameadswereem-beddedinanonviolentprogram(Bushman,2003;seealsoBushman&Phillips,2001).

Televisedsexalsomayimpairmemoryforadvertisedbrands(Bushman&Bonacci,2002).

Aplausiblecauseofthismemoryimpairmentisthatindi-vidualshavealimitedamountofattentiontodirecttowardtele-visionprograms(Lang,Newhagen,&Reeves,1996).

Researchsuggeststhatindividualspaymoreattentiontoviolentmediathantononviolentmedia(Furnham&Gunter,1987;Langetal.

,1996;Williamson,Kosmitzki,&Kibler,1995).

Individualsalsopaymoreattentiontosexualmediathantononsexualmedia(e.

g.

,Geer,Judice,&Jackson,1994;Geer&McGlone,1990).

Fromanevolutionaryperspective,thismakessense.

Ouran-cestorswhopaidattentiontoviolentandsexualcuesweremorelikelytosurviveandpassontheirgenesthanwerethosewhoignoredviolentandsexualcues.

Themoreattentionviewerspaytosexualorviolentprograms,thelessattentiontheyhaveavailableforthecommercialsembeddedinthoseprograms.

Eventhoughcommercialsoccurduringbreaksinaprogram,viewersmaystillbedevotingcognitiveresourcestothinkingabouttheprogramthatattractedtheirattentionsostrongly.

Thepresentstudyprovidesanimportantextensionoverpre-viousstudiesbecauseittestedwhethertelevisedviolenceandsexalsoinuencebuyingintentionsandconsumerbehaviors.

Thisresearchisimportantfortheoreticalandpracticalreasons.

AddresscorrespondencetoBradJ.

Bushman,InstituteforSocialResearch,426ThompsonSt.

,AnnArbor,MI48106;e-mail:bbushman@umich.

edu.

PSYCHOLOGICALSCIENCE702Volume16—Number9Copyrightr2005AmericanPsychologicalSocietyInthetheoryofreasonedaction,behavioralintentionsareviewedasanimportantmediatorofbehavior(e.

g.

,Ajzen&Fishbein,1977).

Thepresentstudyincludedameasureofbuyingintentions,whicharerelatedtoconsumerbehaviors(e.

g.

,Bagozzi,Baumgartner,&Yi,1991,1992;Shimp&Kavas,1984).

Specifically,thisstudytestedwhetherbuyingintentionsme-diatetheeffectofviolenceandsexinaTVprogramonthechoiceofacouponforanadvertisedproduct.

In2000,morethan77%ofAmericansusedcoupons,whichsavedthemmorethan$3.

6billion(CouponUsageStatistics,2000).

Ofcourse,thevalueofthegoodstheypurchasedwasmuchgreaterthanthefacevalueofthecouponstheyused.

Althoughcouponchoicesarenottechnicallyconsumerbehaviors(i.

e.

,theconsumerhastore-deemthecoupon),numerousstudieshaveshownthatcouponsincreaseproductsales(e.

g.

,Ailawadi,Lehmann,&Neslin,2001;Bawa&Shoemaker,1989;Lam,Vandenbosch,Hulland,&Pearce,2001;Schindler,1992).

Couponredeemersarealsoover7timesmorelikelytomakerepeatpurchasesthanarenonredeemers(Taylor,2001).

Insummary,thepresentstudytestedwhethertelevisedvio-lenceandsexreducememoryforanadvertisedproduct,in-tentionstobuythatproduct,andthelikelihoodofchoosingacouponforthatproduct.

Italsotestedwhethermemoryforbrandsisrelatedtobuyingintentionsandcouponchoices.

Televisedviolenceandsexwereexpectedtohaveanindirecteffectoncouponchoices,withbrandmemoryandbuyingin-tentionsservingasimportantmediators.

METHODParticipantsParticipantswere336adults18to54yearsold.

Theiragedis-tributionwasrepresentativeoftheagedistributionof18-to54-year-oldU.

S.

adultswholiveinhouseholdswithTV(i.

e.

,17%ages18–24,12%ages25–29,14%ages30–34,15%ages35–39,16%ages40–44,14%ages45–49,and13%ages50–54;NielsenMediaResearch,2000).

Theseagegroupsarethemostimportanttoadvertisers(Hamilton,1988).

ParticipantswererecruitedusingnewspaperadvertisementsincentralIowa(e.

g.

,DesMoines,Ames).

TheywerewarnedthatsomeoftheTVprogramscontainedviolenceandsex.

Partici-pantsreceived$20inexchangefortheirvoluntaryparticipation.

ProcedureParticipantsweretestedinsmallgroups,buteachworkedin-dependently.

TheyweretoldthattheresearcherswerestudyingattitudestowardTVprograms.

Thesessionswereconductedinacomfortablesetting.

Participantswereseatedinpaddedchairsandweregivensoftdrinksandsnacks(e.

g.

,potatochips,pret-zels,cookies).

Aftergivingtheirinformedconsent,participantswereran-domlyassignedtowatchaTVprogramthatcontainedviolence,sex,violenceandsex,ornoviolenceandsex.

Therewere84participants(42men,42women)ineachofthefourgroups.

Sothatthefourtypesofprogramswouldbeadequatelysampled,sixexemplarsofeachwereused(Wells&Windschitl,1999).

Adiewasrolledtodeterminewhatprogramtoshow.

Thesixviolentprogramswere''24,''''Cops,''''ProtectandServe,''''TerrorontheJob,''''TourofDuty,''and''X-Files.

''Alloftheseprogramshadaviolent(V)contentcode;nonehadasex(S)contentcode.

Thesixsexuallyexplicitprogramswere''AllyMcBeal,''''HowardStern,''''ManShow,''''SexintheCity,''''WildonE,''and''WillandGrace.

''Alloftheseprogramshadasex(S)contentcode;nonehadaviolent(V)contentcode.

Thesixviolentandsexualprogramswere''Angel,''''BuffytheVampireSlayer,''''CSIMi-ami,''''NYPDBlue,''''SouthPark,''and''WorldWrestlingEn-tertainmentRAW.

''Alloftheseprogramshadviolent(V)andsex(S)contentcodes.

Thesixneutralprogramswere''ADatingStory,''''America'sFunniestAnimals,''''HollywoodBeyondtheStars,''''It'saMiracle,''''MiraclePets,''and''TradingSpaces.

''Noneoftheseprogramshadviolent(V)orsex(S)contentcodes.

AlloftheprogramscontainingviolenceorsexwereratedTV-14(ParentsStronglyCautioned).

AlloftheneutralprogramswereratedTV-G(GeneralAudience).

Theadsoriginallyembeddedintheprogramswereeditedout,andthesame12(30-s)adswereembeddedineachprogram.

Becauseconsumersarequiteloyaltobrands(e.

g.

,Chaudhuri,2001),weusedadsforrelativelyunfamiliarbrands(i.

e.

,BodyFantasies,Dermoplast,FerraroRaffaelloChocolates,JoseOle,LibmanNittyGrittyRollerMop,Mederma,NatraTaste,NewSkin,NutraNails,Proheart6,SenokotNaturalVegetableLaxative,andSuddenChangeUndereyeLift).

Therewerethreecommercialbreaksatap-proximately12min,24min,and36minintoeachprogram.

Fouradswerepresentedineachbreak.

Tworandomordersofadswereused.

ImmediatelyafterviewingtheTVprogram,participantsratedhowexciting,boring,involving,humorous,violent,andsexuallyarousingtheythoughtitwas,usingascalerangingfrom1(notatall)to10(extremely).

Theviolenceandsexualarousalratingswereusedasmanipulationchecksfortheprogramcontentcodes.

TheotherratingswereusedascovariatestocontrolfordifferencesamongTVprogramsotherthandifferencesinviolentandsexualcontent.

AfterratingtheTVprogram,participantsreceivedsur-prisememorytests.

First,theylistedasmanybrandnamesastheycouldrecall.

Second,theyreceivedalistofproducts.

Foreachtypeofproduct(e.

g.

,sugarsubstitute),fourbrandswerelisted—theadvertisedbrand(e.

g.

,NatraTaste)andthreefoilbrands(e.

g.

,SugarTwin,SweetDeal,Sweet'n'Smart).

Aswiththeactualbrands,foilbrandsthatwouldberelativelyunfamiliartomostparticipantswereselected.

Foreachkindofproduct,participantscircledthebrandthatwasadvertised.

Volume16—Number9703BradJ.

BushmanNext,participantsreportedtheirbuyingintentionsusingthesamelist.

Foreachtypeofproduct,theycircledthebrandthey''wouldbemostlikelytobuy.

''Thenumberofcouponsselectedforadvertisedproductswasusedasameasureofconsumerbehavior.

Couponsforall40brandsonthelistwereavailable,andparticipantscouldchoose10.

Becauseinadequatefacevaluesoncouponscanreducetheireffectiveness(Chakraborty&Cole,1991;Cheong,2003),allofthecouponsofferedparticipants$1offthelistedprice—asub-stantialsavingsfortheproductsusedinthisstudy,andabout30centshigherthantheaveragecouponfacevalue(PromotionMarketingAssociation,2000).

Professionallyprinted(bogus)couponswereavailablefortheadvertisedandfoilbrands.

Next,participantsreportedtheirdemographics(i.

e.

,age,gender,ethnicbackground)andtheirtelevisionviewinghabits(i.

e.

,thenumberofhourseachweektheyspentwatchingTVandthepercentageoftimetheyspentwatchingviolentandsexualprograms).

Thelattermeasureswereusedtocontrolforhabitualexposuretotelevisedviolenceandsex.

Participantsalsore-portediftheyhadseentheassignedprogrambefore(thatepi-sodeoranyepisodes),iftheyhadseenanyoftheadsbefore,andiftheyhadheardofanyoftheadvertisedproductsbefore.

TheseresponseswereusedtocontrolforpreviousexposuretotheTVprogramsandads.

Finally,participantswerefullydebriefed.

Becausethecouponswerebogus,wegaveparticipantsthefacevalueofthecouponsinstead(i.

e.

,$10).

Thus,eachparticipantreceived$30($20forparticipatinginthestudyand$10fortheboguscoupons).

RESULTSPreliminaryAnalysesandManipulationChecksViolenceRatingsTypeofTVprogramhadasignificanteffectonviolenceratings,F(3,332)5173.

56,p.

05.

Thus,thedatawerecollapsedacrossexemplarsofprogramtypesforsubsequentanalyses.

DemographicDataThedemographicvariables(i.

e.

,sex,age,ethnicbackground)hadnomaineffectsonanyoftheoutcomemeasuresandwereTABLE1MeanViolenceandSexRatings,Memory,BuyingIntentions,andConsumerBehaviorsintheFourConditionsVariableConditionNeutralViolenceSexViolenceandsexViolencerating(1–10)1.

31b(0.

20)6.

12a(0.

20)1.

61b(0.

20)5.

82a(0.

20)Sexrating(1–10)1.

05b(0.

15)1.

43b(0.

15)3.

60a(0.

15)3.

42a(0.

15)NumberofbrandsrecalledAdjusted1.

21a(0.

12)0.

91ab(0.

12)0.

52c(0.

12)0.

72bc(0.

12)Unadjusted1.

18a(0.

12)0.

95ab(0.

12)0.

52c(0.

12)0.

70bc(0.

12)NumberofbrandsrecognizedAdjusted5.

76a(0.

27)4.

36b(0.

28)3.

54c(0.

28)3.

58c(0.

27)Unadjusted5.

70a(0.

28)4.

61b(0.

28)3.

44c(0.

28)3.

50c(0.

28)BuyingintentionsAdjusted5.

61a(0.

26)4.

15b(0.

26)4.

13b(0.

26)4.

16b(0.

26)Unadjusted5.

48a(0.

26)4.

23b(0.

26)4.

23b(0.

26)4.

13b(0.

26)CouponchoicesAdjusted5.

75a(0.

36)4.

31b(0.

37)4.

54b(0.

36)4.

10b(0.

36)Unadjusted5.

50a(0.

36)4.

41b(0.

36)4.

74ab(0.

36)4.

05b(0.

36)Note.

Standarderrorsareinparentheses.

AdjustedmeanswereadjustedforwhetherparticipantshadseentheTVprogram(theepisodeshownaswellasotherepisodes);whethertheyhadseentheadsbefore;whethertheywerefamiliarwiththeproductsadvertised;howexciting,boring,humorous,andinvolvingtheyratedtheTVprogram;howmanyhourstheyspentwatchingTVperweek;andthepercentageoftimetheyspentwatchingtelevisedsexandviolence.

Unadjustedmeanswerenotadjustedforanycovariates.

''Buyingintentions''referstothenumberofadvertisedproductsparticipantsintendedtobuy,and''couponchoices''referstothenumberofadvertisedproductswhosecouponswerechosen.

Withinarow,meanssharingthesamesubscriptarenotsignificantlydifferentatthe.

05significancelevel.

704Volume16—Number9ViolenceandSexDon'tSellnotinvolvedinanysignificantinteractions,ps>.

05.

Thus,thedatawerecollapsedacrossdemographicgroupsforsubsequentanalyses.

RandomOrdersofAdsTwodifferentrandomordersofadswereused.

Becauseran-domizationorderdidnotaffectanyoftheoutcomemeasures(ps>.

05),thedatawerecollapsedacrossthetwoordersofads.

FamiliarityWithAdsandBrandsAsexpected,mostparticipantshadnotseentheadsbeforeandwerenotfamiliarwiththeadvertisedbrands(meannumberofadsseenbefore51.

61,SE50.

13;meannumberoffamiliarbrands51.

93,SE50.

15).

PrimaryAnalysesAnalysisofcovariance(ANCOVA)wasusedtotesttheeffectsoftelevisedviolenceandsexontheoutcomemeasures.

CovariatesincludedwhetherparticipantshadseentheTVprogram(theepisodeshownaswellasotherepisodes);whethertheyhadseentheadsbefore;whethertheywerefamiliarwiththeadvertisedbrands;howexciting,boring,humorous,andinvolvingtheyratedtheTVprogram;howmanyhourstheyspentwatchingTVperweek;andthepercentageoftimetheyspentwatchingtele-visedviolenceandsex.

Theresults,however,weresimilarwhennocovariateswereincludedintheanalyses(seeTable1).

IfasignificanteffectwasfoundfortypeofTVprogram,aplannedcontrastwasperformedtotestwhetherparticipantswhosawaprogramwithoutviolenceandsexrespondeddifferentlyfromparticipantswhosawaprogramwithviolenceorsex.

Onthebasisofpreviousresearch,nodifferencesbetweenviolentandsexualprogrammingwerepredicted(Bushman&Bonacci,2002).

Thus,therespectivecontrastweightsfortheneutral,violent,sexual,andviolentsexualprogramswere3,11,11,and11.

Posthocttestswerealsoconductedtoexplorepossiblediffer-encesbetweenviolentandsexualprogramming(seeTable1).

CouponChoicesTypeofTVprogramsignificantlyinuencedwhetherpartici-pantsselectedcouponsforadvertisedbrands,F(3,320)54.

16,p<.

007(seeTable1).

Participantswhowatchedaprogramwithoutviolenceandsexselected33%morecouponsforadvertisedbrandsthandidparticipantswhowatchedaprogramwithviolenceorsex,F(1,320)511.

05,p<.

001,rpb5.

14.

1Posthoccomparisonsshowedsimilareffectsforviolentandsexualprogrammingoncouponchoices(seeTable1).

Onlyonecovariatewassignificant.

Themoretelevisionparticipantswatched,themorelikelytheyweretochoosecouponsforadvertisedbrands,F(1,320)54.

20,p<.

05,r5.

16.

BuyingIntentionsForeachtypeofproduct,participantsindicatedthebrandtheyweremostlikelytobuy.

TypeofTVprogramsignificantlyin-uencedbuyingintentions,F(3,320)58.

00,p<.

0001(seeTable1).

Participantswhowatchedaprogramwithoutviolenceandsexselected35%moreoftheadvertisedbrandsthandidparticipantswhowatchedaprogramwithviolenceorsex,F(1,320)523.

35,p<.

0001,rpb5.

23.

Posthoccomparisonsshowedsimilareffectsforviolentandsexualprogrammingonbuyingintentions(seeTable1).

Noneofthecovariatesweresignificant.

RecallTypeofTVprogramsignificantlyinuencedbrandrecall,F(3,320)56.

51,p<.

0003(seeTable1).

Brandrecallwas68%higherforpeoplewhosawaprogramwithoutviolenceandsexthanforpeoplewhosawaprogramwithviolenceorsex,F(1,320)513.

98,p<.

0002,rpb5.

18.

Therecallimpairmenttendedtobelargerforsexualprogrammingthanforviolentprogramming(seeTable1).

Onlyonecovariatewassignificant.

Brandrecallwaspositivelycorrelatedwiththenumberofad-vertisedproductsparticipantswerefamiliarwith,F(1,320)56.

94,p<.

009,r5.

27.

RecognitionTypeofTVprogramsignificantlyinuencedbrandrecognition,F(3,320)514.

25,p<.

0001(seeTable1).

Brandrecognitionwas51%higherforparticipantswhosawaprogramwithoutviolenceandsexthanforparticipantswhosawaprogramwithviolenceorsex,F(1,320)536.

62,p<.

0001,rpb5.

29.

Therecognitionimpairmenttendedtobelargerforsexualpro-grammingthanforviolentprogramming(seeTable1).

Brandrecognitionwasalsopositivelycorrelatedwiththenumberofproductsparticipantswerefamiliarwith,F(1,320)513.

71,p<.

0003,r5.

31.

TheRoleofMemoryandBuyingIntentionsinCouponChoicesStructuralequationmodelswerecomputedwithAMOSusingmaximumlikelihoodestimation(Arbuckle,1999).

Thehy-pothesizedmodelwasthatbrandmemoryandbuyingintentionsmediatetheeffectofTVviolenceandsexoncouponchoices.

Inspecifyingthemodel,adummyvariablewasusedtorepresentTVviolenceandsex(violentorsexualprogram51,neutralprogram50).

Brandmemorywastreatedasalatentvariable,measuredusingbrandrecallandrecognition.

Thevariance-covariancematrixusedfortheanalysesisgiveninTable2.

Thehypothesizedmediationmodeltthedataextremelywell,w2(5,N5336)54.

76,p<.

45,GFI(goodness-of-tindex)5.

995,1ThecomparativepercentagesreportedhereandlaterinResultswerecal-culatedbysummingthevaluesfortheparticipantswhowatchedviolentpro-gramming,sexualprogramming,andviolentsexualprogramming;dividingby3;andthendividingtheresultintothevaluefortheparticipantswhowatchedneutralprogramming:neutral/[(violence1sex1violenceandsex)/3].

Forex-ample,usingthedatainTable1,onecanseethatthenumberofadvertisedbrandswhosecouponswerechosenwas33%higherforparticipantswhosawaneutralprogramthanfortheothergroups:5.

75/[(4.

3114.

5414.

10)/3]51.

33,or33%higher.

Volume16—Number9705BradJ.

BushmanCFI(comparativetindex)51,RMSEA(rootmeansquareerrorofapproximation)5.

005.

AscanbeseeninFigure1,TVvio-lenceandseximpairedbrandmemory.

Brandmemoryandbuyingintentionswereimportantmediators.

Peopleintendedtobuybrandstheycouldremember,andtheychosecouponsforbrandstheyintendedtobuy.

AnalternativemodelincludeddirectpathsfromTVviolenceandsextobuyingintentionsandtocouponchoice.

Becausethemediationmodelisnestedwithinthisalternativemodel,achi-squaredifferencetestcanbeusedtocomparethetwomodels.

Thedifferencetestwasnonsignificant,w2(3,N5336)53.

68,p<.

30.

Thus,TVviolenceandsexdidnothaveadirecteffectonbuyingintentionsorcouponchoice.

TheeffectsofTVviolenceandsexoncouponchoicewereindirect,throughbrandmemoryandbuyingintentions.

Similaranalyseswereperformedtotesttheseparateeffectsofviolenceandsexonbrandmemory,buyingintentions,andcouponchoices.

TheseanalysesfoundsimilareffectsforTVviolenceandsex(seetheappendix).

DISCUSSIONItiscommonlyassumedthatviolenceandsexsellproducts,buttheymightactuallyhavetheoppositeeffect.

Thepresentstudyreplicatespreviousstudiesshowingthattelevisedviolenceandseximpairmemoryforadvertisedproducts.

Becausetelevisedviolenceandsexhadsimilareffectsonrecallandrecognition,thememoryfailureisprobablyduetoencodingratherthanre-trieval.

Televisedviolenceandsexalsodecreasedintentionstobuytheadvertisedbrandsandreducedthenumberofadver-tisedbrandswhosecouponsparticipantschose.

Memoryisanimportantoutcomemeasure,becauseitispositivelyrelatedtobuyingintentionsandcouponchoices.

Itistruethatviolentandsexyprogramsattractyoungviewers,andthisagegroupishighlydesirabletoadvertisers.

However,theeffectsinthepresentresearchheldformenandwomenofallages,regardlessofwhethertheylikedtowatchviolentorsexualprograms.

Theobtainedresultsareconsistentwiththetheoryofreasonedaction(e.

g.

,Ajzen&Fishbein,1977),whichpositsthatbe-havioralintentionsmediatetheeffectofapersuasivemessageonbehavior.

Inthepresentstudy,buyingintentionsmediatedtheeffectoftelevisedviolenceandsexoncouponchoices.

Thepresentstudyhasimportantpracticalimplicationsforsociety.

IfadvertisersrefusedtosponsorviolentandsexualTVprograms,suchprogramswouldbecomeextinct.

About60%ofTVprogramscontainviolenceorsex(Kunkeletal.

,1999;Na-tionalTelevisionViolenceStudy,1998).

TVviolenceandsexcanhaveanegativeimpactonsociety.

Researchfromhundredsofstudiesconductedoverseveraldecadeshasshownthattele-visedviolenceincreasessocietalviolence(e.

g.

,Anderson&Bushman,2002).

Sexuallyexplicitmediapromotesexualcal-lousness,cynicalattitudesaboutloveandmarriage,andper-ceptionsthatpromiscuityisthenorm(e.

g.

,Allen,Emmers,&Gebhardt,1995;Zillmann,2000).

Moreover,mediainwhichsexiscombinedwithviolencemayhaveparticularlyperniciouseffects(e.

g.

,Allen,D'Alessio,&Brezgel,1995;Linz,Donner-TABLE2Variance-CovarianceMatrixfortheStructuralEquationAnalysesMeasure123451.

TVviolenceorsex0.

18(0.

750).

18n.

29n.

23n.

14n2.

Brandrecall0.

0851.

174(0.

839).

58n.

33n.

18n3.

Brandrecognition0.

3491.

7377.

618(4.

313).

51n.

21n4.

Buyingintentions0.

2410.

8563.

3885.

833(4.

515).

37n5.

Consumerbehavior0.

2070.

6551.

9882.

95911.

229(4.

676)Note.

N5336.

Variancesandmeans(inparentheses)areonthediagonal;covariancesarebelowthediagonal.

Fordescriptivepurposes,correlationsareabovethediagonal.

np<.

05.

Fig.

1.

Effectoftelevisionviolenceandsexonviewers'consumerbehavior(i.

e.

,choosingcouponsforadvertisedbrands).

Theanalysisdepictedheretestedbrandmemoryandbuyingintentionsasmediatorsoftheeffect.

Asterisksindicatesignificantpathcoefcients,np<.

05.

Standardizedestimatesareshown.

706Volume16—Number9ViolenceandSexDon'tSellstein,&Penrod,1988).

Thus,sponsoringviolentandsexualprogramsmightbebadforsocietyandbadforbusiness.

Acknowledgments—ThisresearchwasfundedinpartbyaresearchgrantfromIowaStateUniversity.

IwouldliketothankRebeccaMarzenandLauraValenzianofortheirhelprecordingtheprograms,NicoleOswaltforherhelptestingparticipants,andMikeGillespieforhishelpwiththestructuralequationanalyses.

IalsowouldliketothankRowellHuesmannforhishelpfulfeedbackonadraftofthismanuscript.

REFERENCESAilawadi,K.

L.

,Lehmann,D.

R.

,&Neslin,S.

A.

(2001).

Marketresponsetoamajorpolicychangeinthemarketingmix:LearningfromProcter&Gamble'svaluepricingstrategy.

JournalofMarketing,65,44–61.

Ajzen,I.

,&Fishbein,M.

(1977).

Attitude-behaviorrelations:Atheo-reticalanalysisandreviewofempiricalresearch.

PsychologicalBulletin,84,888–914.

Allen,M.

,D'Alessio,D.

,&Brezgel,K.

A.

(1995).

Ameta-analysissummarizingtheeffectsofpornography:II.

Aggressionafterex-posure.

HumanCommunicationResearch,22,258–283.

Allen,M.

,Emmers,T.

,&Gebhardt,L.

(1995).

Exposuretopornographyandacceptanceoftherapemyths.

JournalofCommunication,45,5–26.

AmericanPsychologicalAssociation.

(1993).

Violenceandyouth:Psychology'sresponse.

Washington,DC:Author.

Anderson,C.

A.

,&Bushman,B.

J.

(2002).

Mediaviolenceandsocietalviolence.

Science,295,2377–2378.

Arbuckle,J.

L.

(1999).

AMOS(Version4.

01)[Computersoftware].

Chicago:SmallWatersCorp.

Bagozzi,R.

P.

,Baumgartner,H.

,&Yi,Y.

(1991).

Couponusageandthetheoryofreasonedaction.

AdvancesinConsumerResearch,8,24–27.

Bagozzi,R.

P.

,Baumgartner,H.

,&Yi,Y.

(1992).

Stateversusactionorientationandthetheoryofreasonedaction:Anapplicationtocouponusage.

JournalofConsumerResearch,18,505–518.

Bawa,K.

,&Shoemaker,R.

(1989).

Analyzingincrementalsalesfromadirectmailcouponpromotion.

JournalofMarketing,53,66–78.

Bushman,B.

J.

(2003,August).

Ifthetelevisionprogrambleeds,memoryfortheadvertisementrecedes.

PaperpresentedattheannualmeetingoftheAmericanPsychologicalAssociation,Toronto,Ontario,Canada.

Bushman,B.

J.

,&Bonacci,A.

M.

(2002).

Violenceandseximpairmemoryfortelevisionads.

JournalofAppliedPsychology,87,557–564.

Bushman,B.

J.

,&Phillips,C.

M.

(2001).

Ifthetelevisionprogrambleeds,memoryfortheadvertisementrecedes.

CurrentDirectionsinPsychologicalScience,10,44–47.

Chakraborty,G.

,&Cole,C.

(1991).

Theeffectsofcouponcharacter-isticsonbrandchoice:Alaboratorystudy.

PsychologyandMar-keting,8,145–159.

Chaudhuri,A.

(2001).

Thechainofeffectsfrombrandtrustandbrandaffecttobrandperformance:Theroleofbrandloyalty.

JournalofMarketing,65,81–93.

Cheong,K.

J.

(2003).

Observations:Arecents-offcouponseffectiveJournalofAdvertisingResearch,33,73–78.

Furnham,A.

,&Gunter,B.

(1987).

Effectsoftimeofdayandmediumofpresentationonimmediaterecallofviolentandnonviolentnews.

AppliedCognitivePsychology,1,255–262.

Geer,J.

H.

,Judice,S.

,&Jackson,S.

(1994).

Readingtimesforeroticmaterial:Thepausetoreect.

TheJournalofGeneralPsychology,121,345–352.

Geer,J.

H.

,&McGlone,M.

S.

(1990).

Sexdifferencesinmemoryforerotica.

CognitionandEmotion,4,71–78.

Hamilton,J.

T.

(1998).

Channelingviolence:Theeconomicmarketforviolenttelevisionprogramming.

Princeton,NJ:PrincetonUniver-sityPress.

Kim,S.

J.

(1994).

''Viewerdiscretionisadvised'':Astructuralapproachtotheissueoftelevisionviolence.

UniversityofPennsylvaniaLawReview,142,1383–1441.

Kunkel,D.

,Cope,K.

M.

,MaynardFarinola,W.

J.

,Biely,E.

,Rollin,E.

,&Donnerstein,E.

(1999).

SexonTV.

MenloPark,CA:KaiserFamilyFoundation.

Lam,S.

Y.

,Vandenbosch,M.

,Hulland,J.

,&Pearce,M.

(2001).

Eval-uatingpromotionsinshoppingenvironments:Decomposingsalesresponseintoattraction,conversion,andspendingeffects.

Mar-ketingScience,20,194–215.

Lang,A.

,Newhagen,J.

,&Reeves,B.

(1996).

Negativevideoasstructure:Emotion,attention,capacity,andmemory.

JournalofBroadcastingandElectronicMedia,40,460–477.

Linz,D.

G.

,Donnerstein,E.

,&Penrod,S.

(1988).

Effectsoflong-termexposuretoviolentandsexuallydegradingdepictionsofwomen.

JournalofPersonalityandSocialPsychology,55,758–768.

NationalTelevisionViolenceStudy.

(1998).

NationalTelevisionVio-lenceStudy(Vol.

3).

SantaBarbara:UniversityofCalifornia,SantaBarbara,CenterforCommunicationandSocialPolicy.

NielsenMediaResearch.

(2000).

Nielsentelevisionindex,nationalaudiencedemographics(Vol.

1).

NewYork:Author.

ParentsTelevisionCouncil.

(2003).

Sexlosesitsappeal:AstateoftheindustryreportonsexonTV.

RetrievedDecember15,2003,fromhttp://www.

parentstv.

org/ptc/publications/reports/stateindustrysex/main.

aspPromotionMarketingAssociation.

(2000).

Couponusagestatistics.

RetrievedJuly21,2004,fromhttp://couponing.

about.

com/cs/aboutcouponing/a/couponusage2000.

htmSchindler,R.

M.

(1992).

Acouponismorethanalowprice:Evidencefromashopping-simulationstudy.

PsychologyandMarketing,9,431–451.

Shimp,T.

A.

,&Kavas,A.

(1984).

Thetheoryofreasonedactionappliedtocouponusage.

JournalofConsumerResearch,11,795–809.

Sutel,S.

(2004).

NewcropofoddSuperBowladstodebut.

RetrievedJune2005fromAPOnline:http://newslink.

nandomedia.

com/SportServer/football/n/playoffs/v-fresno/story/1127283p-7844151c.

htmlTaylor,G.

A.

(2001).

Couponresponseinservices.

JournalofRetailing,77,139–151.

TelevisionBureauofAdvertising.

(2003).

MediacomparisonstudybytheTelevisionBureauofAdvertising.

(AvailablefromtheTelevisionBureauofAdvertising,3East54thStreet,NewYork,NY10022-3108)Wells,G.

L.

,&Windschitl,P.

D.

(1999).

Stimulussamplingandsocialpsychologicalexperimentation.

PersonalityandSocialPsycholo-gyBulletin,25,1115–1125.

Williamson,S.

S.

,Kosmitzki,C.

,&Kibler,J.

L.

(1995).

Theeffectsofviewingviolenceonattentioninwomen.

TheJournalofPsychol-ogy,129,717–721.

Volume16—Number9707BradJ.

BushmanZillmann,D.

(2000).

Inuenceofunrestrainedaccesstoeroticaonadolescents'andyoungadults'dispositionstowardsexuality.

JournalofAdolescentHealth,27S,41–44.

(RECEIVED2/2/04;REVISIONACCEPTED3/29/05;FINALMATERIALSRECEIVED4/6/05)APPENDIX:SEPARATEEFFECTSOFTVVIOLENCEANDSEXIntheanalysisoftheseparateeffectsofviolentprogramming,adummyvariablewasusedtorepresentTVviolence(violentprogram51,neutralprogram50).

Thehypothesizedmedia-tionmodeltthedataextremelywell,w2(5,N5168)55.

27,p<.

49,GFI5.

988,CFI5.

998,RMSEA5.

018.

Thedirect-effectsmodeldidnotimprovethet,w2(2,N5168)50.

76,p<.

69.

Similarly,intheanalysisoftheseparateeffectsofsexualprogramming,adummyvariablewasusedtorepresentTVsex(sexualprogram51,neutralprogram50).

Thehypothesizedmediationmodeltthedataextremelywell,w2(5,N5168)56.

67,p<.

25,GFI5.

985,CFI5.

991,RMSEA5.

045.

Thedirect-effectsmodeldidnotimprovethet,w2(2,N5168)51.

00,p<.

61.

Similarresultswereobtainedfortheeffectsofprogrammingthatwasbothviolentandsexual.

AdummyvariablewasusedtorepresentTVviolenceandsex(violentandsexualprogram51,neutralprogram50).

Thehypothesizedmediationmodeltthedataextremelywell,w2(5,N5168)53.

61,p<.

61,GFI5.

992,CFI51,RMSEA50.

Thedirect-effectsmodeldidnotimprovethet,w2(2,N5168)50.

76,p<.

68.

Twoadditionalmediationmodelscompareddifferencesbetweenviolentandsexualprogramming.

Forthesemodels,scoresforbrandrecallandbrandrecognitionwerestandardizedandsummedtocreateacompositevariableforbrandmemory.

Thedirect-effectsmodelshad0degreesoffreedom(i.

e.

,satu-ratedmodels)andarenotpresentedherebecausetheyshouldnotbeinterpreted.

Onemodelcomparedprogramswithviolenceandsextoprogramswithonlyviolence.

AdummyvariablewasusedtorepresentTVsex(violentandsexualprogram51,violentprogram50).

Thehypothesizedmediationmodeltthedatawell,w2(3,N5168)53.

39,p<.

34,GFI5.

99,CFI5.

99,RMSEA5.

028.

However,thestandardizedre-gressioncoefcientforthepathbetweentheindicatorvariableandthememoryvariablewasnonsignificant(coefcient5.

07,p5.

853).

Thus,sexdidnotaddanythingabovetheeffectofviolence.

Theothermodelcomparedprogramswithviolenceandsextoprogramswithonlysex.

AdummyvariablewasusedtorepresentTVviolence(violentandsexualprogram51,sexualprogram50).

Thehypothesizedmediationmodeltthedatawell,w2(3,N5168)51.

20,p<.

75,GFI5.

996,CFI51,RMSEA50.

However,thestandardizedregressioncoefcientforthepathbetweentheindicatorvariableandthememoryvariablewasnonsignificant(coefcient5.

17,p5.

814).

Thus,violencedidnotaddanythingabovetheeffectofsex.

708Volume16—Number9ViolenceandSexDon'tSell

易探云:香港CN2云服务器低至18元/月起,183.60元/年

易探云怎么样?易探云最早是主攻香港云服务器的品牌商家,由于之前香港云服务器性价比高、稳定性不错获得了不少用户的支持。易探云推出大量香港云服务器,采用BGP、CN2线路,机房有香港九龙、香港新界、香港沙田、香港葵湾等,香港1核1G低至18元/月,183.60元/年,老站长建站推荐香港2核4G5M+10G数据盘仅799元/年,性价比超强,关键是延迟全球为50ms左右,适合国内境外外贸行业网站等,如果需...

易探云:香港物理机服务器仅550元/月起;E3-1230/16G DDR3/SATA 1TB/香港BGP/20Mbps

易探云怎么样?易探云(yitanyun.com)是一家知名云计算品牌,2017年成立,从业4年之久,目前主要从事出售香港VPS、香港独立服务器、香港站群服务器等,在售VPS线路有三网CN2、CN2 GIA,该公司旗下产品均采用KVM虚拟化架构。目前,易探云推出免备案香港物理机服务器性价比很高,E3-1230 8 核*1/16G DDR3/SATA 1TB/香港BGP线路/20Mbps/不限流量,仅...

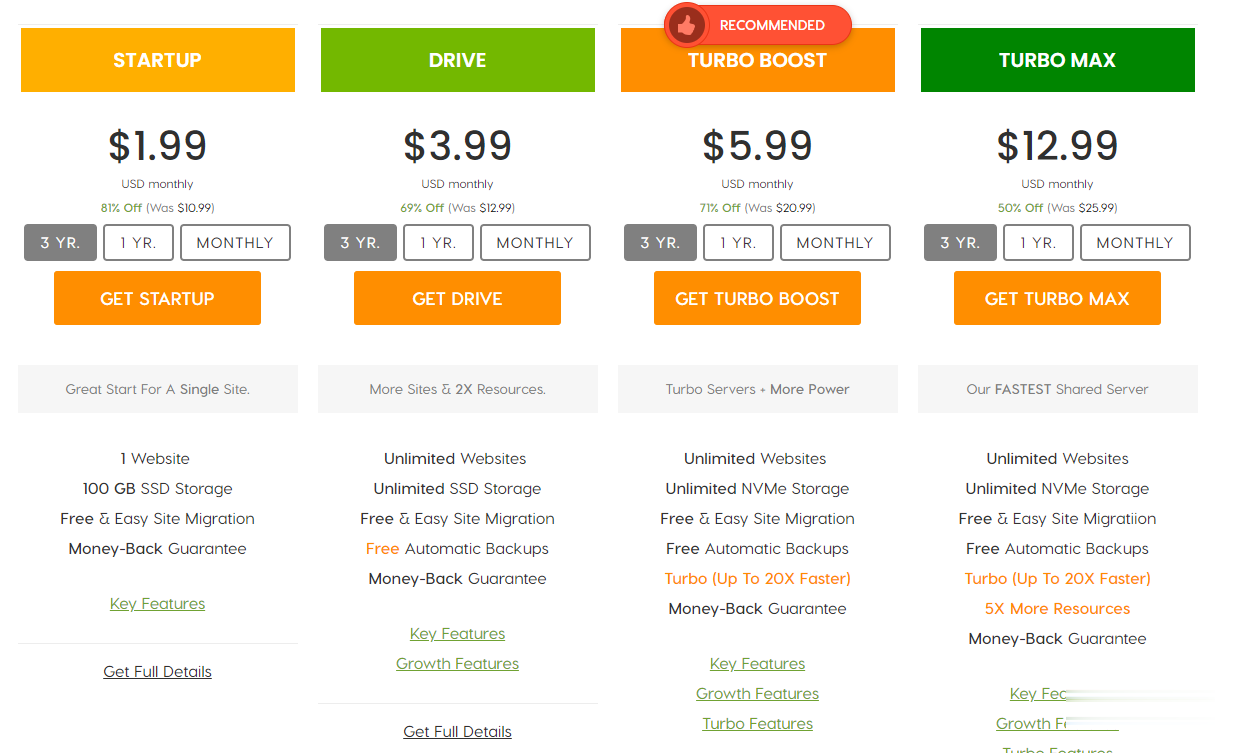

A2Hosting三年付$1.99/月,庆祝18周年/WordPress共享主机最高优惠81%/100GB SSD空间/无限流量

A2Hosting主机,A2Hosting怎么样?A2Hosting是UK2集团下属公司,成立于2003年的老牌国外主机商,产品包括虚拟主机、VPS和独立服务器等,数据中心提供包括美国、新加坡softlayer和荷兰三个地区机房。A2Hosting在国外是一家非常大非常有名气的终合型主机商,拥有几百万的客户,非常值得信赖,国外主机论坛对它家的虚拟主机评价非常不错,当前,A2Hosting主机庆祝1...

zhuo爱为你推荐

-

特朗普吐槽iPhone为什么那么多人吐槽iphoneipad代理想买个ipad买几代性价比比较高文档下载怎么下载百度文档宜人贷官网我在宜人财富贷款2万元,下款的时候时候系统说银行卡号错误,然 我在宜人财富贷款2万我在宜人财富贷款腾讯公司电话腾讯总公司服务热线是多少腾讯公司电话是多少腾讯公司电话是多少tumblr上不去为什么,爱看软件打不开?页面一直在加载即时通平台有好的放单平台吗?123456hd有很多App后面都有hd是什么意思什么是seoseo怎么学呢?