macroporositycomodo官网

comodo官网 时间:2021-01-14 阅读:()

Size-dependentmortalityinaNeotropicalsavannatree:theroleofheight-relatedadjustmentsinhydraulicarchitectureandcarbonallocationpce_20121456.

.

1466YONG-JIANGZHANG1,2,3,FREDERICKC.

MEINZER4,GUANG-YOUHAO1,2,3,FABIANG.

SCHOLZ5,SANDRAJ.

BUCCI5,FREDERICOS.

C.

TAKAHASHI6,RANDOLVILLALOBOS-VEGA2,JUANP.

GIRALDO7,KUN-FANGCAO1,WILLIAMA.

HOFFMANN8&GUILLERMOGOLDSTEIN2,91KeyLaboratoryofTropicalForestEcology,XishuangbannaTropicalBotanicalGarden,ChineseAcademyofSciences,Mengla,Yunnan666303,China,2DepartmentofBiology,UniversityofMiami,POBox249118,CoralGables,FL33124,USA,3GraduateSchooloftheChineseAcademyofSciences,Beijing100039,China,4USDAForestService,ForestrySciencesLaboratory,3200SWJeffersonWay,Corvallis,OR97331,USA,5ConsejoNacionaldeInvestigacionesCienticasyTecnicas(CONICET)andLaboratoriodeEcologiaFuncional,DepartamentodeBiologia,UniversidadNacionaldelaPatagoniaSanJuanBosco,ComodoroRivadavia,Argentina,6DepartamentodeEcologia,UniversidadedeBrasilia,CaixaPostal04457,Brasilia,DF70904970,Brazil,7DepartmentofOrganismicandEvolutionaryBiology,HarvardUniversity,Cambridge,MA02138,USA,8DepartmentofPlantBiology,NorthCarolinaStateUniversity,Raleigh,NC27695-7612,USAand9ConsejoNacionaldeInvestigacionesCienticasyTecnicas(CONICET)andLaboratoriodeEcologíaFuncional,DepartamentodeEcologia,GeneticayEvolucion,FacultaddeCienciasExactasyNaturales,UniversidaddeBuenosAires,CiudadUniversitaria,Nuez,BuenosAires,ArgentinaABSTRACTSize-relatedchangesinhydraulicarchitecture,carbonallocationandgasexchangeofSclerolobiumpaniculatum(Leguminosae),adominanttreespeciesinNeotropicalsavannasofcentralBrazil(Cerrado),wereinvestigatedtoassesstheirpotentialroleinthediebackoftallindivi-duals.

Treesgreaterthan~6-m-tallexhibitedmorebranchdamage,largernumbersofdeadindividuals,higherwooddensity,greaterleafmassperarea,lowerleafareatosapwoodarearatio(LA/SA),lowerstomatalconductanceandlowernetCO2assimilationthansmalltrees.

Stem-specichydraulicconductivitydecreased,whileleaf-specichydraulicconductivityremainednearlyconstant,withincreasingtreesizebecauseoflowerLA/SAinlargertrees.

Leavesweresubstantiallymorevulnerabletoembolismthanstems.

Largetreeshadlowermaximumleafhydraulicconductance(Kleaf)thansmalltreesandalltreesizesexhib-itedlowerKleafatmiddaythanatdawn.

Thesesize-relatedadjustmentsinhydraulicarchitectureandcarbonallocationapparentlyincurredalargephysiologicalcost:largetreesreceivedalowerreturnincarbongainfromtheirinvest-mentinstemandleafbiomasscomparedwithsmalltrees.

Additionally,largetreesmayexperiencemoreseverewaterdecitsindryyearsduetolowercapacityforbufferingtheeffectsofhydraulicpath-lengthandsoilwaterdecits.

Key-words:carbonbalance;hydraulicconductivity;popula-tiondynamics;treedieback;xylemcavitation.

INTRODUCTIONTreemortalityandtheconsequentreleaseofcarbonandnutrientsareimportantprocessesthatinuencethestruc-ture,composition,dynamicsandfunctioningofwoodyeco-systems(Franklin,Shugart&Harmon1987).

Treedieback,thesynchronizedmortalityofanentirepopulationoracohortofthatpopulation,isaphenomenonthathasbeendocumentedinavarietyoftreespeciesandecosystemtypes(e.

g.

Watt1987;Woodman1987;Gerrish,Mueller-Dombois&Bridges1988;Crombie&Tippett1990;MacGregor&O'Connor2002;Riceetal.

2004).

Factorscontributingtotreediebackincludeairpollution(Woodman1987),her-bivorybyinsects(Haugen&Underdown1990),fungalinfection(Crombie&Tippett1990),climatechange(Watt1987),nutrientlimitation(Gerrishetal.

1988)anddrought(MacGregor&O'Connor2002;Riceetal.

2004).

Fre-quently,deathoftreesisattributedtomorethanonetrig-geringagent,andistheresultofacombinationofbioticandabioticfactors(Manion&Lachance1992).

However,diebackcouldalsobeanaturalrecurringphenomenonresultingfromcohortsenescence(Mueller-Dombois1985)orrelatedtoreproduction(Foster1977)ratherthanfromdiseasesorenvironmentalstresses.

DiebackinAustralianandAfricansavannashasbeenattributedtotheeffectsofdrought(MacGregor&O'Connor2002;Riceetal.

2004),buttoourknowledge,notreediebackhasbeenreportedandnostudieshavebeendonetolinktreephysiologicalprocessesandpopulationdynamicsforNeotropicalsavannas.

Sincesavannaecosystemsareusuallycharacterizedbystrongseasonalityinprecipitation,plant–waterrelationsareconsideredtobekeydeterminantsoftheirstructureCorrespondence:F.

C.

Meinzer.

Fax:+15417587760;e-mail:rick.

meinzer@oregonstate.

eduPlant,CellandEnvironment(2009)32,1456–1466doi:10.

1111/j.

1365-3040.

2009.

02012.

x2009BlackwellPublishingLtd1456andcomposition(Huntley&Walker1982).

Drought,ingeneral,notonlyinuencesthewaterrelationsandhydrau-licpropertiesofplantsbutalsonegativelyaffectsphotosyn-thesis(Chavesetal.

2002),aswellasresistancetoherbivory(Lowman&Heatwole1992)andinfectionbyfungi(Gibbsetal.

1990).

CentralBraziliansavannas(Cerrado)aresub-jectedtoapronounceddryseasonthatmaylastforaslongas5months.

Waterdecitsplayacrucialroleinthegrowthandphysiologyofsavannatreesbecauseofthehighatmo-sphericevaporativedemandandthelimitedamountofwaterthattreescanobtaindailyfromtheuppersoillayersduringthedryseason(Meinzeretal.

1999).

Althoughmanysavannawoodyspecieshavedeeprootsystemsthataccesswateravailableatdepthduringthedryseason(Rawitscher1948;Oliveiraetal.

2005),theparadigmthattheyallhavesimilaraccesstodeepsoilwaterreservesdoesnotappeartobeuniversallyapplicable(Jacksonetal.

1999;Buccietal.

2005;Goldsteinetal.

2008;Scholzetal.

2008).

Waterdecitsareampliedintalltreesowingtoincreasedtensioninthexylemrequiredtodrawwaterfromthesoiltothecanopy.

Increasedtensioninxylemconduitsintalltreesmayinduceembolismandhydraulicdysfunc-tion,leadingtoincreasedwaterdecits,decreasedstomatalconductance(gs)andphotosynthesis,lowergrowthrates(Ryan&Yoder1997;Kochetal.

2004;Woodruff,Bond&Meinzer2004;Ryan,Phillips&Bond2006;Domecetal.

2008)and,eventually,treemortality.

Inordertomitigatetheeffectsofincreasedwaterdecits,treesmaydecreasegs,down-regulatephotosynthesis,intensifyrellingofembo-lizedxylemand/ormodifytheirhydraulicarchitecture,inparticular,theleafareatosapwoodarearatio(LA/SA)(McDowelletal.

2002).

Recently,ithasbeenshownthatleavesareahydraulicbottleneckinthewatertransportpathwayoftheplant,representingabout30%ofwholeplantresistanceforarangeoflifeforms(Sacketal.

2003)andthatmaximumleafhydraulicconductance(Kleaf)decreaseswithincreasingheight(Woodruff,Meinzer&Lachenbruch2008).

Therelationshipbetweenadjustmentinhydraulicarchitecturewhengrowingtallerandwhole-treecarbonbalance,aswellastheirrolesintreemortality,however,ispoorlyunderstood.

SclerolobiumpaniculatumVog.

(Leguminosae)isadomi-nanttallevergreensavannaspeciesexhibitingconspicuousbranchdiebackandtreemortalityamonglargerindividuals.

Itisafast-growingpioneerspecies(Pires&Marcati2005)andisamongthefewBrazilianCerradotreespecieswithrelativelyshallowrootsystems(Jacksonetal.

1999;Scholz2006).

Theobjectiveofthisstudywastoidentifypotentialcausalrelationshipsbetweensize-relatedchangesintreehydraulicarchitecture,carbonallocation,growth,gasexchange,waterdecitsandmortalityinS.

paniculatumtreesgrowinginaCerradositewhererehasbeenexcludedduringthelast35years.

Weinvestigatedstemandleafhydraulicproperties,leafwaterstatus,growthrates,gasexchangeandotherfunctionaltraitssuchaswooddensityandleafmassperarea(LMA)inS.

paniculatumtreesofdifferentheights.

MATERIALSANDMETHODSStudysiteandplantmaterialThisresearchwascarriedoutinasavannasiteattheInsti-tutoBrasileirodeGeograaeEstatística(IBGE)reserve,aeldexperimentalstationlocated35kmsouthofBrasilia(15°56′S,47°53′W,elevation1100m).

Averageannualpre-cipitationinthereserveis1500mmwithapronounceddryseasonfromMaytoSeptember.

Averagerelativehumidityduringthedryseasonis55%andminimumrelativehumid-itycandroptovaluesaslowas10%.

Meanmonthlytem-peraturesrangefrom19to23°C.

Thesoilsareverynutrientpoor,deepandwell-drainedoxisols.

Soilbulkdensityisabout0.

99gcm-3,macroporosityisabout18%andtexturefraction(silt/clay)isabout0.

22intheupper100cmofatypicalsoilprole(Buccietal.

2008).

TheIBGEreservecontainsallmajorphysiognomictypesofsavannasfromveryopentoclosedsavannas.

Sclerolobiumpaniculatumisadominantspeciesinsavannaswithahightreedensityandexhibitshighchronicmortalityoflargetrees.

A'cerradodenso'sitewithrelativelyuniformtopogra-phyandsoilcharacteristicsandintermediatetreedensitywaschosentominimizeshadingeffectsandincreasethelikelihoodthatsmallandlargetreesexperiencedsimilarlightregimes.

Firehadbeenexcludedfromthesiteformorethan35years.

AlloftheS.

paniculatumtreesinsidea200-m-long,40-m-widetransectweresurveyedandlatercatego-rizedintofourheightclassesformeasurementsoffunctionaltraits(Table1).

Boththeheightandstemdiam-eterat1.

3m(DBH)oftheindividualsusedforphysiologi-calstudiesweredetermined.

ThepercentageofdeadbranchespertreeofeachS.

paniculatumindividualwasdeterminedbycountingthetotalnumberofdeadbranchesperplantinsmallertrees,orvisuallyestimatingthepercent-agesofdeadbranchesinthecrownsoftallertreesinwhichTable1.

Numberofindividualsusedforphysiologicalmeasurements,height,DBHandrelativeabundanceoftreesineachsizeclassTreeheightclass(m)NumberofindividualsHeight(m)DBH(cm)Relativeabundance(%)8118.

950.

1916.

260.

8842TheheightandDBHvaluesaremeansSEfromallthesampledtreesusedtomeasurephysiologicalvariables.

TherelativeabundancecorrespondstoallSclerolobiumpaniculatumtreesinthestudysite,eveniftheyweredead.

Size-dependentmortalityinaNeotropicalsavannatree14572009BlackwellPublishingLtd,Plant,CellandEnvironment,32,1456–1466branchesweretoonumeroustoaccuratelycountfromtheground.

LeafwaterpotentialApressurechamber(PMS,Corvallis,OR,USA)wasusedtomeasureleafwaterpotential(YL)duringthedryseasonof2006.

Sixto10newestfullydevelopedmatureleavesfromsun-exposedterminalbranchesofdifferentindivi-dualswereselectedtomeasuredawnandmiddayYL.

SamplesfordawnYLwerecollectedbetween0630and0730h,whileleavesformiddaymeasurementswerecol-lectedbetween1230and1400h.

PreviousstudiesattheIBGEreservehaveshownthatdailymaximum(leastnega-tive)valuesofYLaretypicallyattainedbetween0600and0630hwithadeclineof0.

2MPaby0730h(Buccietal.

2003,2004a).

Thetoptwoleaetsofthelargecompoundleaveswereexcised,immediatelysealedinplasticbagsandkeptinacoolerwithsmallamountoficeuntilbalancingpressuresweredeterminedinthelaboratorywithin1hofsamplecollection.

Kleaf,pressure-volumerelationshipsandleafcapacitanceKleafwasestimatedusingthepartialrehydrationmethod(Brodribb&Holbrook2003).

SamplesfordawnKleafwerecollectedbetween0630and0730h,whileleavesformiddaymeasurementswerecollectedbetween1230and1400h.

Largebrancheswerecut,baggedandkeptinthedarkwithslightlywetpapertowelsforabout30minforwaterpoten-tialequilibrationofleavesandleaets.

TwoleaveswerechosentomeasuretheinitialYLinthetwotopleaetsofthecompoundleaf.

Then,thetoptwoleaetsoftwoadja-centleaveswerecutfromtherachisunderwater,andallowedtoabsorbwaterfor3to15sdependingontheinitialwaterpotential,afterwhich,theirrachisendsweredriedcarefully.

ThenalvalueofYLwasimmediatelymea-suredusingthepressurechamber.

Kleafwasthencalculatedfromtheequation:KCtleafof=*()lnΨΨ(1)whereCistheleafcapacitance,YoistheYLpriortorehy-drationandYfistheYLafterrehydrationfortseconds.

ValuesofleafcapacitanceusedtocalculateKleafwerederivedfrompressure–volumerelationships(Tyree&Hammel1972)usingthemethoddescribedbyBrodribb&Holbrook(2003).

Briey,theYLcorrespondingtoturgorlosswasestimatedastheinectionpoint(thetransitionfromtheinitialcurvilinear,steeperportionofthecurvetothemorelinearlesssteepportion)ofthegraphofYLversusrelativewatercontent(RWC).

TheslopeofthecurvepriortoandfollowingturgorlossprovidedCintermsofRWC(CRWC)forpre-turgorlossandpost-turgorloss,respectively.

LeafareatodrymassratioswereusedtonormalizeConaleafareabasis.

Pressure–volumecurvesweredeterminedforsixfullydevelopedexposedleavesfromdifferentindividuals.

Leavesforpressure–volumeanalyseswereobtainedfrombranchescutintheeldintheearlymorning,re-cutimmediatelyunderwaterandcoveredwithblackplasticbagswiththecutendinwaterforabout2huntilmeasurementsbegan.

Datawerettedbyapressure–volumeprogramdevelopedbySchulte&Hinckley(1985).

LeafvulnerabilitycurveswereplottedasKleafagainstinitialYLbeforerehydration.

ArangeofYLwasattainedthroughslowbenchdryingofleafybranchescollectedfromtheeldatdawn.

Branchesweredehydratedfordifferenttimeperiods,afterwhich,theywereenclosedinblackplasticbagswithslightlywetpapertowels.

After0.

5to1hequilibrationperiod,YL,beforeandafterrehydration,weremeasured.

StemhydraulicconductivityHydraulicconductivity(kh)wasmeasuredonsun-exposedterminalbranchesexcisedatdawn(0630to0730h)andmidday(1300to1400h)fromfourtoveindividualsofeachheightclassexceptthesmallest(6mtallexhibitedslightlylowervulnerabilitytoembolismthanthoseofsmalltrees.

TheY50was-0.

8MPainleavesoftrees8mtall(Fig.

3).

They-interceptofthefunctionttedtoYLversusKleafrelationships(KleafataYLof0MPa)was22mmolm-2s-1MPa-1fortrees>8mtall,whileitrangedfrom30to40mmolm-2s-1MPa-1fortreesintheotherheightclasses.

Leafturgorlosspointsrangedbetween-1.

5and-1.

7MPa,andcoincidedapproximatelywiththeYLatwhichKleafapproachedzero(Fig.

3).

Stem-specichydraulicconductivity(ks)didnotchangesignicantlybetweendawnandmidday(Fig.

4).

Ontheotherhand,middayKleafwassubstantiallylowercomparedwithdawnvaluesintreesfromallsizeclasses(Fig.

4).

Therewasamarginallysignicant(P=0.

06)declineindawnKleafwithincreasingtreeheight.

ThemiddayKleafvalueswereslightlyhigherthanthevaluesderivedfromleafvulnerabil-itycurvesandmiddayYL,probablyasaresultoftheequili-brationbetweenleafandstemwaterpotentials,whilethebranchesremainedbaggedbeforemeasurements.

Sincenosignicantdifferencewasfoundbetweendawnandmiddaykh,ksandkl(datanotshownforkhandkl),themeansofmiddayanddawnvalueswereusedinFig.

5.

Therewasasignicant(P=0.

003)height-relateddeclineinkh(Fig.

5).

ksalsodecreasedsignicantly(P6mtallfallingfurtherbelowtheYLatturgorlossthanintrees8mtall.

Inplantsfromaridenvironments,rehydra-tionofsamplesforpressure–volumeanalysismaysome-timescauseartefactsbyshiftingtheturgorlosspointtolessnegativevalues(Meinzeretal.

1986).

However,CerradotreesexperienceYLcloseto0MPaatnightandFigure3.

Leafandstemhydraulicvulnerabilitycurvesfortreesindifferentheightclasses.

Asigmoidfunctionwasttedtothedata(P8Kleaf(mmolm–2s–1MPa–1)0102030*******Figure4.

Dawn(blackbars)andmidday(greybars)stem-specichydraulicconductivity(ks),andleafhydraulicconductance(Kleaf),oftreesfromdifferentheightclasses.

ksoftreesshorterthan3mwasnotmeasured(seemethods).

BarsaremeansSEforn=4to6.

SignicantdifferencesbetweendawnandmiddayKleafwerefound(**P8LA/SA(m2cm–2)0.

00.

10.

20.

30.

40.

50.

60.

7Treeheight(m)3to66to8>8Kl(x10–4kgm–1s–1MPa–1)024681012141462Y.

-J.

Zhangetal.

2009BlackwellPublishingLtd,Plant,CellandEnvironment,32,1456–1466atabout-1MPa,whereasstemswere50%embolizedbelow-3.

2MPa(Fig.

3).

StemxylemwasoperatingfarfromthepointofcatastrophicdysfunctionsensuTyree&Sperry(1988),andthereforeterminalstemshadawidersafetymarginintermsofwaterdecitsthanleaves.

LeafwaterpotentialsatwhichKleafreachedminimumvalueswereclosetotheirturgorlosspoints.

ThemortalityofS.

panicu-latumtreesisnotlikelytoresultfromcatastrophicstemxylemdysfunctionduringperiodsofdroughtbecauseminimumstemwaterpotentialsintheeldwerenotonlywellabovethosecorrespondingtoP50,butalsowellabovethewaterpotentialthresholdatwhichcavitationstartstoincreaseaccordingtothestemxylemvulnerabilitycurves.

Ontheotherhand,YLintheeldandleafvulnerabilitycurvessuggestthatembolisminleavesoccurredregularly.

LowermaximumKleafintallerS.

paniculatumtreesmayreectheight-relatedtrendsinxylemstructureassociatedwithreducedleafexpansion(Woodruffetal.

2008).

LeavesofS.

paniculatumshowedaconsistentdailypatternofdepressionandrecoveryofKleaf(Fig.

4).

DailychangesinKleafcouldbepartiallyexplainedbyembolismformationduringthemorningwhenYLdecreasedasevapo-rativedemandandtranspirationincreased.

Intheafternoonoratnight,Kleafincreased,consistentwithdailyembolismrepair.

ResultsofdyeexperimentsbyBuccietal.

(2003)supportthehypothesisthatdielvariationofpetiolekhofsavannatreeswasassociatedwithembolismformationandrepair.

Dyeexperimentsaredifculttoperformwiththeleaflamina,butresultsobtainedwithothertechniques,LMA(gcm–2)0.

0160.

0170.

0180.

0190.

0200.

021Leafsize(cm2)200250300350Treeheight(m)8Wooddensity(gcm–3)0.

560.

580.

600.

620.

640.

660.

68Figure6.

Leafmassperarea(LMA),leafsizeandwooddensityoftreesindifferentheightclasses.

BarsaremeansSEofsixindividuals.

gs(mmolg–1s–1)0123456A(mmolg–1s–1)0.

000.

020.

040.

060.

080.

100.

120.

14Treeheight(m)0246810A/gs(mmolmol–1)020406080100r2=0.

40r2=0.

30r2=0.

31Figure7.

Stomatalconductance(gs),netassimilationrate(A)andintrinsicwateruseefciency(A/gs)inrelationtoheightofS.

paniculatumtrees.

Thelinesarelinearregressionsttedtothedata.

Size-dependentmortalityinaNeotropicalsavannatree14632009BlackwellPublishingLtd,Plant,CellandEnvironment,32,1456–1466suchascryoscanningelectronmicroscopy(Canny2001;Woodruffetal.

2007)andacousticemission(e.

g.

LoGulloetal.

2003;Johnsonetal.

2009),indicatethatcavitationcommonlyoccursinleavesofmanyspecies.

Cochardetal.

(2004),ontheotherhand,suggestedthatdiurnalvariationsinKleafofconiferscouldbepartiallyexplainedbychangesinconduitdimensionsundercyclesoftensionincreaseandtensionrelease,reversiblyconstrictingthewaterowthroughtheleaf.

RegardlessofthemechanismgoverningdiurnalchangesinKleaf,thereversiblelossofhydraulicconductanceintheleaflaminamaybeanadaptivemeansofamplifyingtheevaporativedemandsignaltothestomatainordertoexpe-diteastomatalresponse(Brodribb&Holbrook2004).

Althoughwedidnotnddailychangesinksofstemsinourstudy,diurnaldepressionandrecoveryofstemkshasbeenobservedinotherspecies(Zwieniecki&Holbrook1998;Melcheretal.

2001).

Embolismformationandrellingisprobablyoflimitedsignicanceforstemsofwoodyplantsatmosttimesbecauseofthehighenergeticcostsofrellingalargevolumeoftissuethatisdistantfromthesitesofcarbohydratesynthesisintheleaves.

Comparedwithstems,diurnalrellinginleavesmaybelessenergeticallycostlyandmayinvolvesimplermechanisms(Buccietal.

2003;Brodribb&Holbrook2004).

Sclerolobiumpaniculatumstemswerelessvulnerabletocavitationthanleavesononehand,andalsowereprotectedbyregulationoftranspira-tionthroughdiurnaldepressionandrecoveryofKleaf.

DuetothehighsafetyofS.

paniculatumstems,andtheeffectiveregulationofKleafandgs,thediebackoftallindividualscouldnotbeexplainedbycatastrophicxylemdysfunctionwhenexperiencingdroughtbutmayberelatedtochangesinwhole-treewaterandcarbonbalanceresultingfromsize-relatedstructuralchanges,asdiscussedbelow.

CarbonbalanceinrelationtohydraulicarchitectureandcarbonallocationTreesadjustedtheirbranchhydraulicarchitecturewithincreasingheight,resultinginlowerLA/SAintallertreesandarelativelyconstantkl,sotheamountofwaterthatcouldbedeliveredbythevascularsystemperunitleafareawassimilarindifferentsizetreesdespiteasharpreductioninbranchkswithincreasingtreesize.

Theserelationshipswerenotdirectlycharacterizedatthewhole-treelevel,butsize-dependentincreasesinbranchdiebackandsimilarvaluesofdawnandmiddayYLacrosssizeclasseswereconsistentwithmaintenanceofwhole-treeleaf-specicconductance.

SeasonaladjustmentsinleafareaofCerradotreeshavebeenshowntoreduceseasonalvariationinmiddayYLandwhole-plantleaf-specicconductance(Buccietal.

2005).

Otherstudieshaveshowncompensatoryadjustmentsintreeallometryandstandstructurethatcon-tributetohomeostasisofminimumYL(Whitehead,Jarvis&Waring1984;Williams&Cooper2005).

Nevertheless,adjustmentsthatmaintainanadequatewaterbalancecouldresultinanunsustainablesituationintermsofwhole-treecarbonbalanceinS.

paniculatum.

ThelargestS.

paniculatumtreesarelikelytoreceiveasubstantiallylowerreturnincarbongainfromtheirinvestmentinstemandleafbiomasscomparedwithsmallertreesasexplainedinthefollowingexercisebasedonourdataonsize-dependentchangesinallometry,carbonallocationandgasexchange.

Foragiveninvestmentinsapwoodarea,thelargesttrees(>8mtall)displayonly55%asmuchleafareacomparedwith3to6-m-talltrees(LA/SA=0.

33and0.

60m2cm-2intrees>8mtalland3to6mtall,respectively).

WhenthedifferencesabovearenormalizedbythedifferenceinbranchwooddensityandLMAbetweenthelargesttreesandsmallertrees(anestimateoftheamountofleafmassdevelopedperbiomassinvested),thenthelargesttreesdevelopedonly54%asmuchleafmassperbiomassinvestedinstemtissue.

Furthermore,accordingtothelinearrelationshipbetweenA(massbasednetCO2uptake)andH(treeheight)(A=0.

122-0.

0062H),Aintrees10mtallwouldbeabout64%ofthatintrees3to6mtall.

Thus,largetreesmayonlyget35%asmuchcarbonreturnperbiomassinvestedassmalltreesdo.

ItisnoteworthythatAofdetachedshootsdeclinedby~50%between1and10m(Fig.

7),suggestingthatthisheight-relatedchangewasasso-ciatedwithinherentleafstructuralandphysiologicalcon-straintsongasexchange(e.

g.

Niinemets2002;Woodruffetal.

2009)ratherthanextrinsiceffectsofhydraulicpath-lengthresistances.

Gasexchangeofattachedshootsislikelytodeclinemoresteeplywithincreasingheightbecauseofhydraulicconstraints(Schfer,Oren&Tenhunen2000;McDowell,Licata&Bond2005).

Sclerolobiumpaniculatumisafast-growingpioneerspecieswitharelativelyshortlifecycle.

Thesespeciesshouldhaveallocationpatternsthatfavoursurvivalandgrowthofyoungtrees,eveniftheperformanceofthesametreeiscompromisedwhenolder(Williams1957).

InS.

pan-iculatum,patternsofhydraulicarchitectureadoptedearlyindevelopmentappeartoconstrainwaterandcarbonrela-tionslateindevelopment.

Highadultmortalityhasalsobeenfoundinmonocarpicspecies(Stearns1992),alifehistorystrategyinwhichindividualsreproduceonlyonceandsubsequentlydie.

SeveralspeciesofTachigali,agenusnowconsideredsynonymouswithSclerolobium(Lewis2005),aremonocarpic(Foster1977;Poorteretal.

2005),anextremelyrarecharacteristicfortropicaltrees.

IftheobservedpatternsofhydraulicarchitectureandcarbonimbalancerepresentmoregeneralcharacteristicsoftheSclerolobium–Tachigaliclade,thissuggeststhathydraulicconstraintsmayhaveresultedinthelife-historytrade-offresponsibleforthemonocarpyinsomeTachigalispecies.

TheheightoftallS.

paniculatumtreesmayconferanadvantageincompetitionforlightandestablishingdomi-nance,particularlyindenseCerradophysiognomies,butmayalsocarrytheriskofgreaterwaterdecitsinexcep-tionallydryyears.

Compensatoryadjustmentsinleafandbranchhydraulicarchitecturewithincreasingtreeheightappearedtocarryalargephysiologicalcost:apoorreturnincarbongainforagiveninvestmentinstemandleafbiomasscomparedwithsmalltrees,whicheventuallycouldleadtodiebackofthewholetree.

Ourresultsprovideapotential1464Y.

-J.

Zhangetal.

2009BlackwellPublishingLtd,Plant,CellandEnvironment,32,1456–1466explanationforthemassmortalityinlargeS.

paniculatumtrees,aswellasinsightsintothephysiologicalcostsofsize-relatedchangesincarbonallocationpatterns.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSWethanktheReservaEcologicadoInstitutoBrasileirodeGeograaeEstatistica(IBGE)forlogisticsupport.

WealsothankEricManzanéforhelpwitheldwork,aswellasDavidJanos,CatalinaAristizábal,TaniaWyss,SarahGaramzegiandXinWangforhelpfulcommentsonthemanuscript.

ThisstudywassupportedbyNationalScienceFoundation(USA)grants#0296174and#0322051.

ThisworkcomplieswithBrazilianlaw.

REFERENCESAbramoffM.

D.

,MagelhaesP.

J.

&RamS.

J.

(2004)Imageprocess-ingwithImagej.

BiophotonicsInternational11,36–42.

BrodribbT.

J.

&HolbrookN.

M.

(2003)Stomatalclosureduringleafdehydration,correlationwithotherleafphysiologicaltraits.

PlantPhysiology132,2166–2173.

BrodribbT.

J.

&HolbrookN.

M.

(2004)Stomatalprotectionagainsthydraulicfailure:acomparisonofcoexistingfernsandangiosperms.

NewPhytologist162,663–670.

BucciS.

J.

,ScholzF.

G.

,GoldsteinG.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,SternbergL.

&DaS.

L.

(2003)Dynamicchangesinhydraulicconductivityinpetiolesoftwosavannatreespecies:factorsandmechanismscontributingtotherellingofembolizedvessels.

Plant,Cell&Environment26,1633–1645.

BucciS.

J.

,ScholzF.

G.

,GoldsteinG.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,HinojosaJ.

A.

,HoffmannW.

A.

&FrancoA.

C.

(2004a)Processespreventingnocturnalequilibrationbetweenleafandsoilwaterpotentialintropicalsavannawoodyspecies.

TreePhysiology24,1119–1127.

BucciS.

J.

,GoldsteinG.

H.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,ScholzF.

G.

,FrancoA.

C.

&BustamanteM.

(2004b)Functionalconvergenceinhydraulicarchitectureandwaterrelationsoftropicalsavannatrees:fromleaftowholeplant.

TreePhysiology24,891–899.

BucciS.

J.

,GoldsteinG.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,FrancoA.

C.

,CampanelloP.

&ScholzF.

G.

(2005)Mechanismscontributingtoseasonalhomeostasisofminimumleafwaterpotentialandpredawndis-equilibriumbetweensoilandplantsinNeotropicalsavannatrees.

Trees19,296–304.

BucciS.

J.

,ScholzF.

G.

,GoldsteinG.

,HoffmannW.

A.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,FrancoA.

C.

,GiambellucaT.

&Miralles-WilhelmF.

(2008)Con-trolsonstandtranspirationandsoilwaterutilizationalongatreedensitygradientinaNeotropicalsavanna.

AgriculturalandForestMeteorology148,839–849.

CannyM.

(2001)Embolismandrellinginthemaizeleaflaminaandtheroleoftheprotoxylemlacuna.

AmericanJournalofBotany88,47–51.

ChavesM.

M.

,PereiraJ.

S.

,MarocoJ.

,RodriguesM.

L.

,RicardoC.

P.

,OsorioM.

L.

,CarvalhoI.

,FariaT.

&PinheiroC.

(2002)HowplantscopewithwaterstressintheeldPhotosynthesisandgrowth.

AnnalsofBotany89,907–916.

CochardH.

,FrouxF.

,MayrS.

&CoutardC.

(2004)Xylemwallcollapseinwater-stressedpineneedles.

PlantPhysiology134,401–408.

CrombieD.

S.

&TippettJ.

T.

(1990)Acomparisonofwaterrela-tions,visualsymptoms,andchangesinstemgirthforevaluatingimpactofPhytophthoracinnamomionEucalyptusmarginata.

CanadianJournalofForestResources20,233–240.

DomecJ.

-C.

,LachenbruchB.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,WoodruffD.

R.

,WarrenJ.

M.

&McCullohK.

A.

(2008)Maximumheightinaconiferisassociatedwithconictingrequirementsforxylemdesign.

ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciencesoftheUnitedStatesofAmerica105,12069–12074.

FosterR.

B.

(1977)TachigaliaversicolorisasuicidalNeotropicaltree.

Nature268,624–626.

FranklinJ.

F.

,ShugartH.

H.

&HarmonM.

E.

(1987)Treedeathasanecologicalprocess.

Bioscience37,550–556.

GerrishG.

,Mueller-DomboisD.

&BridgesK.

W.

(1988)NutrientlimitationandMetrosiderosforestdiebackinHawaii.

Ecology69,723–727.

GibbsR.

,CraigI.

,MyersB.

J.

&YuanZ.

Q.

(1990)EffectofdroughtanddefoliationonthesusceptibilityofeucalyptstocankerscausedbyEndothiagyrosaandBotryoshaeriaribis.

AustralianJournalofBotany38,571–581.

GoldsteinG.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,BucciS.

J.

,ScholzF.

G.

,FrancoA.

C.

&HoffmannW.

A.

(2008)WatereconomyofNeotropicalsavanna:sixparadigmsrevisited.

TreePhysiology28,395–404.

HaugenD.

A.

&UnderdownM.

G.

(1990)Sirexnoctiliocontrolprograminresponsetothe1987GreenTriangleoutbreak.

AustralianForestry53,33–40.

HuntleyB.

J.

&WalkerB.

H.

(1982)EcologyofTropicalSavanna.

Springer,Heidelburg,Germany.

JacksonP.

C.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,BustamanteM.

,GoldsteinG.

,FrancoA.

,RundelP.

W.

,CaldasL.

S.

,IglerE.

&CausinF.

(1999)Parti-tioningofsoilwateramongtreespeciesinaBrazilianCerradoecosystem.

TreePhysiology36,237–268.

JamesS.

A.

,ClearwaterM.

J.

,MeinzerF.

C.

&GoldsteinG.

(2002)Heatdissipationsensorsofvariablelengthforthemeasurementofsapowintreeswithdeepsapwood.

TreePhysiology22,277–283.

JohnsonD.

M.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,WoodruffD.

R.

&McCullohK.

A.

(2009)Leafxylemembolism,detectedacousticallyandbycryo-SEM,correspondstodecreasesinleafhydraulicconductanceinfourevergreenspecies.

Plant,Cell&Environment32,828–836.

KochG.

W.

,SillettS.

C.

,JenningsG.

M.

&DavisS.

D.

(2004)Thelimitstotreeheight.

Nature428,851–854.

LewisG.

P.

(2005)LegumesoftheWorld.

RoyalBotanicGardens,Kew,Richmond,UK.

LoGulloM.

A.

,NardiniA.

,TriioP.

&SalleoS.

(2003)ChangesinleafhydraulicandstomatalconductancefollowingdroughtstressandirrigationinCeratoniasiliqua(Carobtree).

Physiolo-giaPlantarum117,186–194.

LowmanM.

D.

&HeatwoleH.

(1992)Spatialandtemporalvari-abilityindefoliationofAustralianeucalypts.

Ecology73,129–142.

McDowellN.

,BarnardH.

,BondB.

J.

,etal.

(2002)Therelationshipbetweentreeheightandleafarea:sapwoodarearatio.

Oecologia132,12–20.

McDowellN.

G.

,LicataJ.

&BondB.

J.

(2005)Environmentalsen-sitivityofgasexchangeindifferent-sizedtrees.

Oecologia145,9–20.

MacGregorS.

D.

&O'ConnorT.

G.

(2002)PatchdiebackofColo-phospermummopaneinadysfunctionalsemi-aridAfricansavanna.

AustralEcology27,385–395.

ManionP.

D.

&LachanceD.

(1992)ForestDeclineConcepts.

APSPress,St.

Paul,MN,USA.

MeinzerF.

C.

,RundelP.

W.

,ShariM.

R.

&NilsenE.

T.

(1986)TurgorandosmoticrelationsofthedesertshrubLarreatriden-tata.

Plant,Cell&Environment9,467–475.

MeinzerF.

C.

,GoldsteinG.

,FrancoA.

C.

,BustamanteM.

,IglerE.

,JacksonP.

,CaldasL.

&RundelP.

W.

(1999)AtmosphericandhydrauliclimitationsontranspirationinBrazilianCerradowoodyspecies.

FunctionalEcology13,273–282.

MeinzerF.

C.

,CampanelloP.

I.

,DomecJ.

C.

,GattiM.

G.

,GoldsteinG.

,Villalobos-VegaR.

&WoodruffD.

R.

(2008)ConstraintsonphysiologicalfunctionassociatedwithbrancharchitectureandSize-dependentmortalityinaNeotropicalsavannatree14652009BlackwellPublishingLtd,Plant,CellandEnvironment,32,1456–1466wooddensityintropicalforesttrees.

TreePhysiology28,1609–1617.

MelcherP.

J.

,GoldsteinG.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,YountD.

,JonesT.

,Hol-brookN.

M.

&HuangC.

X.

(2001)WaterrelationsofcoastalandestuarineRhizophoramangle:xylemtensionanddynamicsofembolismformationandrepair.

Oecologia126,182–192.

Mueller-DomboisD.

(1985)Ohi'adiebackandprotectionmanage-mentoftheHawaiianrainforest.

InHawaii'sTerrestrialEcosys-temsPreservationandManagement(edsC.

P.

Stone&J.

M.

Scott)pp.

403–421.

CooperativeNationalParkResourcesStudiesUnit,UniversityofHawaii,Honolulu,HI,USA.

Niinemets,.

(2002)StomatalconductancealonedoesnotexplainthedeclineinfoliarphotosyntheticrateswithincreasingtreeageandsizeinPiceaabiesandPinussylvestris.

TreePhysiology22,515–535.

OliveiraR.

S.

,BezerraL.

,DavidsonE.

A.

,PintoF.

,KlinkC.

A.

,NepstadD.

C.

&MoreiraA.

(2005)DeeprootfunctioninsoilwaterdynamicsincerradosavannasofcentralBrazil.

FunctionalEcology19,574–581.

PiresI.

P.

&MarcatiC.

R.

(2005)AnatomiaeusodamadeiradeduasvariedadesdeSclerolobiumpaniculatumVog.

dosuldoMaranhao,Brazil.

ActaBotanicaBrasilica19,669–678.

PoorterL.

,ZuidemaP.

A.

,Pena-ClarosM.

&BootR.

G.

A.

(2005)Amonocarpictreespeciesinapolycarpicworld:howcanTachigalivasqueziimaintainitselfsosuccessfullyinatropicalrainforestcommunityJournalofEcology93,268–278.

RawitscherF.

(1948)ThewatereconomyofthevegetationofthecamposcerradosinsouthernBrazil.

JournalofEcology36,237–267.

RiceK.

J.

,MatznerS.

L.

,ByerW.

&BrownJ.

R.

(2004)PatternsoftreediebackinQueensland,Australia:theimportanceofdroughtstressandtheroleofresistancetocavitaion.

Oecologia139,190–198.

RyanM.

J.

&YoderB.

J.

(1997)Hydrauliclimitstotreeheightandtreegrowth.

Bioscience47,235–242.

RyanM.

J.

,PhillipsN.

&BondB.

J.

(2006)Thehydrauliclimitationhypothesisrevisited.

Plant,Cell&Environment29,367–381.

SackL.

,CowanP.

D.

,JaikumarN.

&HolbrookN.

M.

(2003)The'hydrology'ofleaves:coordinationofstructureandfunctionintemperatewoodyspecies.

Plant,Cell&Environment26,1343–1356.

SalaA.

&HochG.

(2009)Height-relatedgrowthdeclinesinponderosapinearenotduetocarbonlimitation.

Plant,Cell&Environment32,22–30.

SchferK.

V.

R.

,OrenR.

&TenhunenJ.

D.

(2000)Theeffectoftreeheightoncrownlevelstomatalconductance.

Plant,Cell&Environment23,365–375.

ScholzF.

G.

(2006)Biosicadeltransportedeaguaenelsistemasuelo-planta:redistribucion,resistenciasycapacitanciashidrauli-cas.

PhDthesis,UniversityofBuenosAires,Argentina.

ScholzF.

G.

,BucciS.

J.

,GoldsteinG.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,FrancoA.

C.

&Miralles-WilhelmF.

(2007)Biophysicalpropertiesandfunc-tionalsignicanceofstemwaterstoragetissuesinNeotropicalsavannatrees.

Plant,Cell&Environment30,236–248.

ScholzF.

G.

,BucciS.

J.

,GoldsteinG.

,MoreiraM.

Z.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,DomecJ.

-C.

,VillalobosVegaR.

,FrancoA.

C.

&Miralles-WilhelmF.

(2008)Biophysicalandlifehistorydetermi-nantsofhydraulicliftinNeotropicalsavannatrees.

FunctionalEcology22,773–786.

doi:10.

1111/j.

1365-2435.

2008.

01452.

xSchulteP.

J.

&HinckleyT.

M.

(1985)Acomparisonofpressure–volumecurvedataanalysistechniques.

JournalofExperimentalBotany36,590–602.

StearnsS.

C.

(1992)TheEvolutionofLifeHistoryStrategies.

OxfordUniversityPress,Oxford,UK.

TyreeM.

T.

&HammelH.

T.

(1972)Themeasurementoftheturgorpressureandthewaterrelationsofplantsbythepressure-bombtechnique.

JournalofExperimentalBotany23,267–282.

TyreeM.

T.

&SperryJ.

S.

(1988)DowoodyplantsoperatenearthepointofcatastrophicxylemdysfunctioncausedbydynamicwaterstressPlantPhysiology88,574–580.

TyreeM.

T.

&SperryJ.

S.

(1989)Vulnerabilityofxylemtocavitationandembolism.

AnnualReviewofPlantPhysiologyandPlantMolecularBiology40,19–48.

WattK.

E.

F.

(1987)AnalternativeexplanationfortheincreasedforestmortalityinEuropeandNorthAmerica.

DanskSkov-foreningsTidsskrift72,210–224.

WhiteheadD.

,JarvisP.

G.

&WaringR.

H.

(1984)Stomatalconduc-tance,transpirationandresistancetowateruptakeinaPinussylvestrisspacingexperiment.

CanadianJournalofForestResearch14,692–700.

WilliamsC.

A.

&CooperD.

J.

(2005)Mechanismsofripariancottonwooddeclinealongregulatedrivers.

Ecosystems8,382–395.

WilliamsG.

C.

(1957)Pleiotropy,naturalselectionandtheevolu-tionofsenescence.

Evolution11,398–411.

WoodmanJ.

N.

(1987)Pollution-inducedinjuryinNorthAmericanforests:factsandsuspicions.

TreePhysiology3,1–15.

WoodruffD.

R.

,BondB.

J.

&MeinzerF.

C.

(2004)DoesturgorlimitgrowthintalltreesPlant,Cell&Environment27,229–236.

WoodruffD.

R.

,MccullohK.

A.

,WarrenJ.

M.

,MeinzerF.

C.

&LachenbruchB.

(2007)ImpactsoftreeheightonleafhydraulicarchitectureandstomatalcontrolinDouglas-r.

Plant,Cell&Environment30,559–569.

WoodruffD.

R.

,MeinzerF.

C.

&LachenbruchB.

(2008)Height-relatedtrendsinleafxylemanatomyandshoothydraulicchar-acteristicsinatallconifer:safetyversusefciencyinwatertransport.

NewPhytologist180,90–99.

WoodruffD.

R.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,LachenbruchB.

&JohnsonD.

M.

(2009)Coordinationofleafstructureandgasexchangealongaheightgradientinatallconifer.

TreePhysiology29,261–272.

ZimmermannM.

H.

&JejeA.

A.

(1981)Vessel-lengthdistributionofsomeAmericanwoodyplants.

CanadianJournalofBotany59,1882–1892.

ZwienieckiM.

A.

&HolbrookN.

M.

(1998)Diurnalvariationinxylemhydraulicconductivityinwhiteash(FraxinusamericanaL.

),redmaple(AcerrubrumL.

)andredspruce(PicearubensSarg.

).

Plant,Cell&Environment21,1173–1180.

Received4March2009;receivedinrevisedform20May2009;acceptedforpublication20May20091466Y.

-J.

Zhangetal.

2009BlackwellPublishingLtd,Plant,CellandEnvironment,32,1456–1466

.

1466YONG-JIANGZHANG1,2,3,FREDERICKC.

MEINZER4,GUANG-YOUHAO1,2,3,FABIANG.

SCHOLZ5,SANDRAJ.

BUCCI5,FREDERICOS.

C.

TAKAHASHI6,RANDOLVILLALOBOS-VEGA2,JUANP.

GIRALDO7,KUN-FANGCAO1,WILLIAMA.

HOFFMANN8&GUILLERMOGOLDSTEIN2,91KeyLaboratoryofTropicalForestEcology,XishuangbannaTropicalBotanicalGarden,ChineseAcademyofSciences,Mengla,Yunnan666303,China,2DepartmentofBiology,UniversityofMiami,POBox249118,CoralGables,FL33124,USA,3GraduateSchooloftheChineseAcademyofSciences,Beijing100039,China,4USDAForestService,ForestrySciencesLaboratory,3200SWJeffersonWay,Corvallis,OR97331,USA,5ConsejoNacionaldeInvestigacionesCienticasyTecnicas(CONICET)andLaboratoriodeEcologiaFuncional,DepartamentodeBiologia,UniversidadNacionaldelaPatagoniaSanJuanBosco,ComodoroRivadavia,Argentina,6DepartamentodeEcologia,UniversidadedeBrasilia,CaixaPostal04457,Brasilia,DF70904970,Brazil,7DepartmentofOrganismicandEvolutionaryBiology,HarvardUniversity,Cambridge,MA02138,USA,8DepartmentofPlantBiology,NorthCarolinaStateUniversity,Raleigh,NC27695-7612,USAand9ConsejoNacionaldeInvestigacionesCienticasyTecnicas(CONICET)andLaboratoriodeEcologíaFuncional,DepartamentodeEcologia,GeneticayEvolucion,FacultaddeCienciasExactasyNaturales,UniversidaddeBuenosAires,CiudadUniversitaria,Nuez,BuenosAires,ArgentinaABSTRACTSize-relatedchangesinhydraulicarchitecture,carbonallocationandgasexchangeofSclerolobiumpaniculatum(Leguminosae),adominanttreespeciesinNeotropicalsavannasofcentralBrazil(Cerrado),wereinvestigatedtoassesstheirpotentialroleinthediebackoftallindivi-duals.

Treesgreaterthan~6-m-tallexhibitedmorebranchdamage,largernumbersofdeadindividuals,higherwooddensity,greaterleafmassperarea,lowerleafareatosapwoodarearatio(LA/SA),lowerstomatalconductanceandlowernetCO2assimilationthansmalltrees.

Stem-specichydraulicconductivitydecreased,whileleaf-specichydraulicconductivityremainednearlyconstant,withincreasingtreesizebecauseoflowerLA/SAinlargertrees.

Leavesweresubstantiallymorevulnerabletoembolismthanstems.

Largetreeshadlowermaximumleafhydraulicconductance(Kleaf)thansmalltreesandalltreesizesexhib-itedlowerKleafatmiddaythanatdawn.

Thesesize-relatedadjustmentsinhydraulicarchitectureandcarbonallocationapparentlyincurredalargephysiologicalcost:largetreesreceivedalowerreturnincarbongainfromtheirinvest-mentinstemandleafbiomasscomparedwithsmalltrees.

Additionally,largetreesmayexperiencemoreseverewaterdecitsindryyearsduetolowercapacityforbufferingtheeffectsofhydraulicpath-lengthandsoilwaterdecits.

Key-words:carbonbalance;hydraulicconductivity;popula-tiondynamics;treedieback;xylemcavitation.

INTRODUCTIONTreemortalityandtheconsequentreleaseofcarbonandnutrientsareimportantprocessesthatinuencethestruc-ture,composition,dynamicsandfunctioningofwoodyeco-systems(Franklin,Shugart&Harmon1987).

Treedieback,thesynchronizedmortalityofanentirepopulationoracohortofthatpopulation,isaphenomenonthathasbeendocumentedinavarietyoftreespeciesandecosystemtypes(e.

g.

Watt1987;Woodman1987;Gerrish,Mueller-Dombois&Bridges1988;Crombie&Tippett1990;MacGregor&O'Connor2002;Riceetal.

2004).

Factorscontributingtotreediebackincludeairpollution(Woodman1987),her-bivorybyinsects(Haugen&Underdown1990),fungalinfection(Crombie&Tippett1990),climatechange(Watt1987),nutrientlimitation(Gerrishetal.

1988)anddrought(MacGregor&O'Connor2002;Riceetal.

2004).

Fre-quently,deathoftreesisattributedtomorethanonetrig-geringagent,andistheresultofacombinationofbioticandabioticfactors(Manion&Lachance1992).

However,diebackcouldalsobeanaturalrecurringphenomenonresultingfromcohortsenescence(Mueller-Dombois1985)orrelatedtoreproduction(Foster1977)ratherthanfromdiseasesorenvironmentalstresses.

DiebackinAustralianandAfricansavannashasbeenattributedtotheeffectsofdrought(MacGregor&O'Connor2002;Riceetal.

2004),buttoourknowledge,notreediebackhasbeenreportedandnostudieshavebeendonetolinktreephysiologicalprocessesandpopulationdynamicsforNeotropicalsavannas.

Sincesavannaecosystemsareusuallycharacterizedbystrongseasonalityinprecipitation,plant–waterrelationsareconsideredtobekeydeterminantsoftheirstructureCorrespondence:F.

C.

Meinzer.

Fax:+15417587760;e-mail:rick.

meinzer@oregonstate.

eduPlant,CellandEnvironment(2009)32,1456–1466doi:10.

1111/j.

1365-3040.

2009.

02012.

x2009BlackwellPublishingLtd1456andcomposition(Huntley&Walker1982).

Drought,ingeneral,notonlyinuencesthewaterrelationsandhydrau-licpropertiesofplantsbutalsonegativelyaffectsphotosyn-thesis(Chavesetal.

2002),aswellasresistancetoherbivory(Lowman&Heatwole1992)andinfectionbyfungi(Gibbsetal.

1990).

CentralBraziliansavannas(Cerrado)aresub-jectedtoapronounceddryseasonthatmaylastforaslongas5months.

Waterdecitsplayacrucialroleinthegrowthandphysiologyofsavannatreesbecauseofthehighatmo-sphericevaporativedemandandthelimitedamountofwaterthattreescanobtaindailyfromtheuppersoillayersduringthedryseason(Meinzeretal.

1999).

Althoughmanysavannawoodyspecieshavedeeprootsystemsthataccesswateravailableatdepthduringthedryseason(Rawitscher1948;Oliveiraetal.

2005),theparadigmthattheyallhavesimilaraccesstodeepsoilwaterreservesdoesnotappeartobeuniversallyapplicable(Jacksonetal.

1999;Buccietal.

2005;Goldsteinetal.

2008;Scholzetal.

2008).

Waterdecitsareampliedintalltreesowingtoincreasedtensioninthexylemrequiredtodrawwaterfromthesoiltothecanopy.

Increasedtensioninxylemconduitsintalltreesmayinduceembolismandhydraulicdysfunc-tion,leadingtoincreasedwaterdecits,decreasedstomatalconductance(gs)andphotosynthesis,lowergrowthrates(Ryan&Yoder1997;Kochetal.

2004;Woodruff,Bond&Meinzer2004;Ryan,Phillips&Bond2006;Domecetal.

2008)and,eventually,treemortality.

Inordertomitigatetheeffectsofincreasedwaterdecits,treesmaydecreasegs,down-regulatephotosynthesis,intensifyrellingofembo-lizedxylemand/ormodifytheirhydraulicarchitecture,inparticular,theleafareatosapwoodarearatio(LA/SA)(McDowelletal.

2002).

Recently,ithasbeenshownthatleavesareahydraulicbottleneckinthewatertransportpathwayoftheplant,representingabout30%ofwholeplantresistanceforarangeoflifeforms(Sacketal.

2003)andthatmaximumleafhydraulicconductance(Kleaf)decreaseswithincreasingheight(Woodruff,Meinzer&Lachenbruch2008).

Therelationshipbetweenadjustmentinhydraulicarchitecturewhengrowingtallerandwhole-treecarbonbalance,aswellastheirrolesintreemortality,however,ispoorlyunderstood.

SclerolobiumpaniculatumVog.

(Leguminosae)isadomi-nanttallevergreensavannaspeciesexhibitingconspicuousbranchdiebackandtreemortalityamonglargerindividuals.

Itisafast-growingpioneerspecies(Pires&Marcati2005)andisamongthefewBrazilianCerradotreespecieswithrelativelyshallowrootsystems(Jacksonetal.

1999;Scholz2006).

Theobjectiveofthisstudywastoidentifypotentialcausalrelationshipsbetweensize-relatedchangesintreehydraulicarchitecture,carbonallocation,growth,gasexchange,waterdecitsandmortalityinS.

paniculatumtreesgrowinginaCerradositewhererehasbeenexcludedduringthelast35years.

Weinvestigatedstemandleafhydraulicproperties,leafwaterstatus,growthrates,gasexchangeandotherfunctionaltraitssuchaswooddensityandleafmassperarea(LMA)inS.

paniculatumtreesofdifferentheights.

MATERIALSANDMETHODSStudysiteandplantmaterialThisresearchwascarriedoutinasavannasiteattheInsti-tutoBrasileirodeGeograaeEstatística(IBGE)reserve,aeldexperimentalstationlocated35kmsouthofBrasilia(15°56′S,47°53′W,elevation1100m).

Averageannualpre-cipitationinthereserveis1500mmwithapronounceddryseasonfromMaytoSeptember.

Averagerelativehumidityduringthedryseasonis55%andminimumrelativehumid-itycandroptovaluesaslowas10%.

Meanmonthlytem-peraturesrangefrom19to23°C.

Thesoilsareverynutrientpoor,deepandwell-drainedoxisols.

Soilbulkdensityisabout0.

99gcm-3,macroporosityisabout18%andtexturefraction(silt/clay)isabout0.

22intheupper100cmofatypicalsoilprole(Buccietal.

2008).

TheIBGEreservecontainsallmajorphysiognomictypesofsavannasfromveryopentoclosedsavannas.

Sclerolobiumpaniculatumisadominantspeciesinsavannaswithahightreedensityandexhibitshighchronicmortalityoflargetrees.

A'cerradodenso'sitewithrelativelyuniformtopogra-phyandsoilcharacteristicsandintermediatetreedensitywaschosentominimizeshadingeffectsandincreasethelikelihoodthatsmallandlargetreesexperiencedsimilarlightregimes.

Firehadbeenexcludedfromthesiteformorethan35years.

AlloftheS.

paniculatumtreesinsidea200-m-long,40-m-widetransectweresurveyedandlatercatego-rizedintofourheightclassesformeasurementsoffunctionaltraits(Table1).

Boththeheightandstemdiam-eterat1.

3m(DBH)oftheindividualsusedforphysiologi-calstudiesweredetermined.

ThepercentageofdeadbranchespertreeofeachS.

paniculatumindividualwasdeterminedbycountingthetotalnumberofdeadbranchesperplantinsmallertrees,orvisuallyestimatingthepercent-agesofdeadbranchesinthecrownsoftallertreesinwhichTable1.

Numberofindividualsusedforphysiologicalmeasurements,height,DBHandrelativeabundanceoftreesineachsizeclassTreeheightclass(m)NumberofindividualsHeight(m)DBH(cm)Relativeabundance(%)8118.

950.

1916.

260.

8842TheheightandDBHvaluesaremeansSEfromallthesampledtreesusedtomeasurephysiologicalvariables.

TherelativeabundancecorrespondstoallSclerolobiumpaniculatumtreesinthestudysite,eveniftheyweredead.

Size-dependentmortalityinaNeotropicalsavannatree14572009BlackwellPublishingLtd,Plant,CellandEnvironment,32,1456–1466branchesweretoonumeroustoaccuratelycountfromtheground.

LeafwaterpotentialApressurechamber(PMS,Corvallis,OR,USA)wasusedtomeasureleafwaterpotential(YL)duringthedryseasonof2006.

Sixto10newestfullydevelopedmatureleavesfromsun-exposedterminalbranchesofdifferentindivi-dualswereselectedtomeasuredawnandmiddayYL.

SamplesfordawnYLwerecollectedbetween0630and0730h,whileleavesformiddaymeasurementswerecol-lectedbetween1230and1400h.

PreviousstudiesattheIBGEreservehaveshownthatdailymaximum(leastnega-tive)valuesofYLaretypicallyattainedbetween0600and0630hwithadeclineof0.

2MPaby0730h(Buccietal.

2003,2004a).

Thetoptwoleaetsofthelargecompoundleaveswereexcised,immediatelysealedinplasticbagsandkeptinacoolerwithsmallamountoficeuntilbalancingpressuresweredeterminedinthelaboratorywithin1hofsamplecollection.

Kleaf,pressure-volumerelationshipsandleafcapacitanceKleafwasestimatedusingthepartialrehydrationmethod(Brodribb&Holbrook2003).

SamplesfordawnKleafwerecollectedbetween0630and0730h,whileleavesformiddaymeasurementswerecollectedbetween1230and1400h.

Largebrancheswerecut,baggedandkeptinthedarkwithslightlywetpapertowelsforabout30minforwaterpoten-tialequilibrationofleavesandleaets.

TwoleaveswerechosentomeasuretheinitialYLinthetwotopleaetsofthecompoundleaf.

Then,thetoptwoleaetsoftwoadja-centleaveswerecutfromtherachisunderwater,andallowedtoabsorbwaterfor3to15sdependingontheinitialwaterpotential,afterwhich,theirrachisendsweredriedcarefully.

ThenalvalueofYLwasimmediatelymea-suredusingthepressurechamber.

Kleafwasthencalculatedfromtheequation:KCtleafof=*()lnΨΨ(1)whereCistheleafcapacitance,YoistheYLpriortorehy-drationandYfistheYLafterrehydrationfortseconds.

ValuesofleafcapacitanceusedtocalculateKleafwerederivedfrompressure–volumerelationships(Tyree&Hammel1972)usingthemethoddescribedbyBrodribb&Holbrook(2003).

Briey,theYLcorrespondingtoturgorlosswasestimatedastheinectionpoint(thetransitionfromtheinitialcurvilinear,steeperportionofthecurvetothemorelinearlesssteepportion)ofthegraphofYLversusrelativewatercontent(RWC).

TheslopeofthecurvepriortoandfollowingturgorlossprovidedCintermsofRWC(CRWC)forpre-turgorlossandpost-turgorloss,respectively.

LeafareatodrymassratioswereusedtonormalizeConaleafareabasis.

Pressure–volumecurvesweredeterminedforsixfullydevelopedexposedleavesfromdifferentindividuals.

Leavesforpressure–volumeanalyseswereobtainedfrombranchescutintheeldintheearlymorning,re-cutimmediatelyunderwaterandcoveredwithblackplasticbagswiththecutendinwaterforabout2huntilmeasurementsbegan.

Datawerettedbyapressure–volumeprogramdevelopedbySchulte&Hinckley(1985).

LeafvulnerabilitycurveswereplottedasKleafagainstinitialYLbeforerehydration.

ArangeofYLwasattainedthroughslowbenchdryingofleafybranchescollectedfromtheeldatdawn.

Branchesweredehydratedfordifferenttimeperiods,afterwhich,theywereenclosedinblackplasticbagswithslightlywetpapertowels.

After0.

5to1hequilibrationperiod,YL,beforeandafterrehydration,weremeasured.

StemhydraulicconductivityHydraulicconductivity(kh)wasmeasuredonsun-exposedterminalbranchesexcisedatdawn(0630to0730h)andmidday(1300to1400h)fromfourtoveindividualsofeachheightclassexceptthesmallest(6mtallexhibitedslightlylowervulnerabilitytoembolismthanthoseofsmalltrees.

TheY50was-0.

8MPainleavesoftrees8mtall(Fig.

3).

They-interceptofthefunctionttedtoYLversusKleafrelationships(KleafataYLof0MPa)was22mmolm-2s-1MPa-1fortrees>8mtall,whileitrangedfrom30to40mmolm-2s-1MPa-1fortreesintheotherheightclasses.

Leafturgorlosspointsrangedbetween-1.

5and-1.

7MPa,andcoincidedapproximatelywiththeYLatwhichKleafapproachedzero(Fig.

3).

Stem-specichydraulicconductivity(ks)didnotchangesignicantlybetweendawnandmidday(Fig.

4).

Ontheotherhand,middayKleafwassubstantiallylowercomparedwithdawnvaluesintreesfromallsizeclasses(Fig.

4).

Therewasamarginallysignicant(P=0.

06)declineindawnKleafwithincreasingtreeheight.

ThemiddayKleafvalueswereslightlyhigherthanthevaluesderivedfromleafvulnerabil-itycurvesandmiddayYL,probablyasaresultoftheequili-brationbetweenleafandstemwaterpotentials,whilethebranchesremainedbaggedbeforemeasurements.

Sincenosignicantdifferencewasfoundbetweendawnandmiddaykh,ksandkl(datanotshownforkhandkl),themeansofmiddayanddawnvalueswereusedinFig.

5.

Therewasasignicant(P=0.

003)height-relateddeclineinkh(Fig.

5).

ksalsodecreasedsignicantly(P6mtallfallingfurtherbelowtheYLatturgorlossthanintrees8mtall.

Inplantsfromaridenvironments,rehydra-tionofsamplesforpressure–volumeanalysismaysome-timescauseartefactsbyshiftingtheturgorlosspointtolessnegativevalues(Meinzeretal.

1986).

However,CerradotreesexperienceYLcloseto0MPaatnightandFigure3.

Leafandstemhydraulicvulnerabilitycurvesfortreesindifferentheightclasses.

Asigmoidfunctionwasttedtothedata(P8Kleaf(mmolm–2s–1MPa–1)0102030*******Figure4.

Dawn(blackbars)andmidday(greybars)stem-specichydraulicconductivity(ks),andleafhydraulicconductance(Kleaf),oftreesfromdifferentheightclasses.

ksoftreesshorterthan3mwasnotmeasured(seemethods).

BarsaremeansSEforn=4to6.

SignicantdifferencesbetweendawnandmiddayKleafwerefound(**P8LA/SA(m2cm–2)0.

00.

10.

20.

30.

40.

50.

60.

7Treeheight(m)3to66to8>8Kl(x10–4kgm–1s–1MPa–1)024681012141462Y.

-J.

Zhangetal.

2009BlackwellPublishingLtd,Plant,CellandEnvironment,32,1456–1466atabout-1MPa,whereasstemswere50%embolizedbelow-3.

2MPa(Fig.

3).

StemxylemwasoperatingfarfromthepointofcatastrophicdysfunctionsensuTyree&Sperry(1988),andthereforeterminalstemshadawidersafetymarginintermsofwaterdecitsthanleaves.

LeafwaterpotentialsatwhichKleafreachedminimumvalueswereclosetotheirturgorlosspoints.

ThemortalityofS.

panicu-latumtreesisnotlikelytoresultfromcatastrophicstemxylemdysfunctionduringperiodsofdroughtbecauseminimumstemwaterpotentialsintheeldwerenotonlywellabovethosecorrespondingtoP50,butalsowellabovethewaterpotentialthresholdatwhichcavitationstartstoincreaseaccordingtothestemxylemvulnerabilitycurves.

Ontheotherhand,YLintheeldandleafvulnerabilitycurvessuggestthatembolisminleavesoccurredregularly.

LowermaximumKleafintallerS.

paniculatumtreesmayreectheight-relatedtrendsinxylemstructureassociatedwithreducedleafexpansion(Woodruffetal.

2008).

LeavesofS.

paniculatumshowedaconsistentdailypatternofdepressionandrecoveryofKleaf(Fig.

4).

DailychangesinKleafcouldbepartiallyexplainedbyembolismformationduringthemorningwhenYLdecreasedasevapo-rativedemandandtranspirationincreased.

Intheafternoonoratnight,Kleafincreased,consistentwithdailyembolismrepair.

ResultsofdyeexperimentsbyBuccietal.

(2003)supportthehypothesisthatdielvariationofpetiolekhofsavannatreeswasassociatedwithembolismformationandrepair.

Dyeexperimentsaredifculttoperformwiththeleaflamina,butresultsobtainedwithothertechniques,LMA(gcm–2)0.

0160.

0170.

0180.

0190.

0200.

021Leafsize(cm2)200250300350Treeheight(m)8Wooddensity(gcm–3)0.

560.

580.

600.

620.

640.

660.

68Figure6.

Leafmassperarea(LMA),leafsizeandwooddensityoftreesindifferentheightclasses.

BarsaremeansSEofsixindividuals.

gs(mmolg–1s–1)0123456A(mmolg–1s–1)0.

000.

020.

040.

060.

080.

100.

120.

14Treeheight(m)0246810A/gs(mmolmol–1)020406080100r2=0.

40r2=0.

30r2=0.

31Figure7.

Stomatalconductance(gs),netassimilationrate(A)andintrinsicwateruseefciency(A/gs)inrelationtoheightofS.

paniculatumtrees.

Thelinesarelinearregressionsttedtothedata.

Size-dependentmortalityinaNeotropicalsavannatree14632009BlackwellPublishingLtd,Plant,CellandEnvironment,32,1456–1466suchascryoscanningelectronmicroscopy(Canny2001;Woodruffetal.

2007)andacousticemission(e.

g.

LoGulloetal.

2003;Johnsonetal.

2009),indicatethatcavitationcommonlyoccursinleavesofmanyspecies.

Cochardetal.

(2004),ontheotherhand,suggestedthatdiurnalvariationsinKleafofconiferscouldbepartiallyexplainedbychangesinconduitdimensionsundercyclesoftensionincreaseandtensionrelease,reversiblyconstrictingthewaterowthroughtheleaf.

RegardlessofthemechanismgoverningdiurnalchangesinKleaf,thereversiblelossofhydraulicconductanceintheleaflaminamaybeanadaptivemeansofamplifyingtheevaporativedemandsignaltothestomatainordertoexpe-diteastomatalresponse(Brodribb&Holbrook2004).

Althoughwedidnotnddailychangesinksofstemsinourstudy,diurnaldepressionandrecoveryofstemkshasbeenobservedinotherspecies(Zwieniecki&Holbrook1998;Melcheretal.

2001).

Embolismformationandrellingisprobablyoflimitedsignicanceforstemsofwoodyplantsatmosttimesbecauseofthehighenergeticcostsofrellingalargevolumeoftissuethatisdistantfromthesitesofcarbohydratesynthesisintheleaves.

Comparedwithstems,diurnalrellinginleavesmaybelessenergeticallycostlyandmayinvolvesimplermechanisms(Buccietal.

2003;Brodribb&Holbrook2004).

Sclerolobiumpaniculatumstemswerelessvulnerabletocavitationthanleavesononehand,andalsowereprotectedbyregulationoftranspira-tionthroughdiurnaldepressionandrecoveryofKleaf.

DuetothehighsafetyofS.

paniculatumstems,andtheeffectiveregulationofKleafandgs,thediebackoftallindividualscouldnotbeexplainedbycatastrophicxylemdysfunctionwhenexperiencingdroughtbutmayberelatedtochangesinwhole-treewaterandcarbonbalanceresultingfromsize-relatedstructuralchanges,asdiscussedbelow.

CarbonbalanceinrelationtohydraulicarchitectureandcarbonallocationTreesadjustedtheirbranchhydraulicarchitecturewithincreasingheight,resultinginlowerLA/SAintallertreesandarelativelyconstantkl,sotheamountofwaterthatcouldbedeliveredbythevascularsystemperunitleafareawassimilarindifferentsizetreesdespiteasharpreductioninbranchkswithincreasingtreesize.

Theserelationshipswerenotdirectlycharacterizedatthewhole-treelevel,butsize-dependentincreasesinbranchdiebackandsimilarvaluesofdawnandmiddayYLacrosssizeclasseswereconsistentwithmaintenanceofwhole-treeleaf-specicconductance.

SeasonaladjustmentsinleafareaofCerradotreeshavebeenshowntoreduceseasonalvariationinmiddayYLandwhole-plantleaf-specicconductance(Buccietal.

2005).

Otherstudieshaveshowncompensatoryadjustmentsintreeallometryandstandstructurethatcon-tributetohomeostasisofminimumYL(Whitehead,Jarvis&Waring1984;Williams&Cooper2005).

Nevertheless,adjustmentsthatmaintainanadequatewaterbalancecouldresultinanunsustainablesituationintermsofwhole-treecarbonbalanceinS.

paniculatum.

ThelargestS.

paniculatumtreesarelikelytoreceiveasubstantiallylowerreturnincarbongainfromtheirinvestmentinstemandleafbiomasscomparedwithsmallertreesasexplainedinthefollowingexercisebasedonourdataonsize-dependentchangesinallometry,carbonallocationandgasexchange.

Foragiveninvestmentinsapwoodarea,thelargesttrees(>8mtall)displayonly55%asmuchleafareacomparedwith3to6-m-talltrees(LA/SA=0.

33and0.

60m2cm-2intrees>8mtalland3to6mtall,respectively).

WhenthedifferencesabovearenormalizedbythedifferenceinbranchwooddensityandLMAbetweenthelargesttreesandsmallertrees(anestimateoftheamountofleafmassdevelopedperbiomassinvested),thenthelargesttreesdevelopedonly54%asmuchleafmassperbiomassinvestedinstemtissue.

Furthermore,accordingtothelinearrelationshipbetweenA(massbasednetCO2uptake)andH(treeheight)(A=0.

122-0.

0062H),Aintrees10mtallwouldbeabout64%ofthatintrees3to6mtall.

Thus,largetreesmayonlyget35%asmuchcarbonreturnperbiomassinvestedassmalltreesdo.

ItisnoteworthythatAofdetachedshootsdeclinedby~50%between1and10m(Fig.

7),suggestingthatthisheight-relatedchangewasasso-ciatedwithinherentleafstructuralandphysiologicalcon-straintsongasexchange(e.

g.

Niinemets2002;Woodruffetal.

2009)ratherthanextrinsiceffectsofhydraulicpath-lengthresistances.

Gasexchangeofattachedshootsislikelytodeclinemoresteeplywithincreasingheightbecauseofhydraulicconstraints(Schfer,Oren&Tenhunen2000;McDowell,Licata&Bond2005).

Sclerolobiumpaniculatumisafast-growingpioneerspecieswitharelativelyshortlifecycle.

Thesespeciesshouldhaveallocationpatternsthatfavoursurvivalandgrowthofyoungtrees,eveniftheperformanceofthesametreeiscompromisedwhenolder(Williams1957).

InS.

pan-iculatum,patternsofhydraulicarchitectureadoptedearlyindevelopmentappeartoconstrainwaterandcarbonrela-tionslateindevelopment.

Highadultmortalityhasalsobeenfoundinmonocarpicspecies(Stearns1992),alifehistorystrategyinwhichindividualsreproduceonlyonceandsubsequentlydie.

SeveralspeciesofTachigali,agenusnowconsideredsynonymouswithSclerolobium(Lewis2005),aremonocarpic(Foster1977;Poorteretal.

2005),anextremelyrarecharacteristicfortropicaltrees.

IftheobservedpatternsofhydraulicarchitectureandcarbonimbalancerepresentmoregeneralcharacteristicsoftheSclerolobium–Tachigaliclade,thissuggeststhathydraulicconstraintsmayhaveresultedinthelife-historytrade-offresponsibleforthemonocarpyinsomeTachigalispecies.

TheheightoftallS.

paniculatumtreesmayconferanadvantageincompetitionforlightandestablishingdomi-nance,particularlyindenseCerradophysiognomies,butmayalsocarrytheriskofgreaterwaterdecitsinexcep-tionallydryyears.

Compensatoryadjustmentsinleafandbranchhydraulicarchitecturewithincreasingtreeheightappearedtocarryalargephysiologicalcost:apoorreturnincarbongainforagiveninvestmentinstemandleafbiomasscomparedwithsmalltrees,whicheventuallycouldleadtodiebackofthewholetree.

Ourresultsprovideapotential1464Y.

-J.

Zhangetal.

2009BlackwellPublishingLtd,Plant,CellandEnvironment,32,1456–1466explanationforthemassmortalityinlargeS.

paniculatumtrees,aswellasinsightsintothephysiologicalcostsofsize-relatedchangesincarbonallocationpatterns.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSWethanktheReservaEcologicadoInstitutoBrasileirodeGeograaeEstatistica(IBGE)forlogisticsupport.

WealsothankEricManzanéforhelpwitheldwork,aswellasDavidJanos,CatalinaAristizábal,TaniaWyss,SarahGaramzegiandXinWangforhelpfulcommentsonthemanuscript.

ThisstudywassupportedbyNationalScienceFoundation(USA)grants#0296174and#0322051.

ThisworkcomplieswithBrazilianlaw.

REFERENCESAbramoffM.

D.

,MagelhaesP.

J.

&RamS.

J.

(2004)Imageprocess-ingwithImagej.

BiophotonicsInternational11,36–42.

BrodribbT.

J.

&HolbrookN.

M.

(2003)Stomatalclosureduringleafdehydration,correlationwithotherleafphysiologicaltraits.

PlantPhysiology132,2166–2173.

BrodribbT.

J.

&HolbrookN.

M.

(2004)Stomatalprotectionagainsthydraulicfailure:acomparisonofcoexistingfernsandangiosperms.

NewPhytologist162,663–670.

BucciS.

J.

,ScholzF.

G.

,GoldsteinG.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,SternbergL.

&DaS.

L.

(2003)Dynamicchangesinhydraulicconductivityinpetiolesoftwosavannatreespecies:factorsandmechanismscontributingtotherellingofembolizedvessels.

Plant,Cell&Environment26,1633–1645.

BucciS.

J.

,ScholzF.

G.

,GoldsteinG.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,HinojosaJ.

A.

,HoffmannW.

A.

&FrancoA.

C.

(2004a)Processespreventingnocturnalequilibrationbetweenleafandsoilwaterpotentialintropicalsavannawoodyspecies.

TreePhysiology24,1119–1127.

BucciS.

J.

,GoldsteinG.

H.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,ScholzF.

G.

,FrancoA.

C.

&BustamanteM.

(2004b)Functionalconvergenceinhydraulicarchitectureandwaterrelationsoftropicalsavannatrees:fromleaftowholeplant.

TreePhysiology24,891–899.

BucciS.

J.

,GoldsteinG.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,FrancoA.

C.

,CampanelloP.

&ScholzF.

G.

(2005)Mechanismscontributingtoseasonalhomeostasisofminimumleafwaterpotentialandpredawndis-equilibriumbetweensoilandplantsinNeotropicalsavannatrees.

Trees19,296–304.

BucciS.

J.

,ScholzF.

G.

,GoldsteinG.

,HoffmannW.

A.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,FrancoA.

C.

,GiambellucaT.

&Miralles-WilhelmF.

(2008)Con-trolsonstandtranspirationandsoilwaterutilizationalongatreedensitygradientinaNeotropicalsavanna.

AgriculturalandForestMeteorology148,839–849.

CannyM.

(2001)Embolismandrellinginthemaizeleaflaminaandtheroleoftheprotoxylemlacuna.

AmericanJournalofBotany88,47–51.

ChavesM.

M.

,PereiraJ.

S.

,MarocoJ.

,RodriguesM.

L.

,RicardoC.

P.

,OsorioM.

L.

,CarvalhoI.

,FariaT.

&PinheiroC.

(2002)HowplantscopewithwaterstressintheeldPhotosynthesisandgrowth.

AnnalsofBotany89,907–916.

CochardH.

,FrouxF.

,MayrS.

&CoutardC.

(2004)Xylemwallcollapseinwater-stressedpineneedles.

PlantPhysiology134,401–408.

CrombieD.

S.

&TippettJ.

T.

(1990)Acomparisonofwaterrela-tions,visualsymptoms,andchangesinstemgirthforevaluatingimpactofPhytophthoracinnamomionEucalyptusmarginata.

CanadianJournalofForestResources20,233–240.

DomecJ.

-C.

,LachenbruchB.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,WoodruffD.

R.

,WarrenJ.

M.

&McCullohK.

A.

(2008)Maximumheightinaconiferisassociatedwithconictingrequirementsforxylemdesign.

ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciencesoftheUnitedStatesofAmerica105,12069–12074.

FosterR.

B.

(1977)TachigaliaversicolorisasuicidalNeotropicaltree.

Nature268,624–626.

FranklinJ.

F.

,ShugartH.

H.

&HarmonM.

E.

(1987)Treedeathasanecologicalprocess.

Bioscience37,550–556.

GerrishG.

,Mueller-DomboisD.

&BridgesK.

W.

(1988)NutrientlimitationandMetrosiderosforestdiebackinHawaii.

Ecology69,723–727.

GibbsR.

,CraigI.

,MyersB.

J.

&YuanZ.

Q.

(1990)EffectofdroughtanddefoliationonthesusceptibilityofeucalyptstocankerscausedbyEndothiagyrosaandBotryoshaeriaribis.

AustralianJournalofBotany38,571–581.

GoldsteinG.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,BucciS.

J.

,ScholzF.

G.

,FrancoA.

C.

&HoffmannW.

A.

(2008)WatereconomyofNeotropicalsavanna:sixparadigmsrevisited.

TreePhysiology28,395–404.

HaugenD.

A.

&UnderdownM.

G.

(1990)Sirexnoctiliocontrolprograminresponsetothe1987GreenTriangleoutbreak.

AustralianForestry53,33–40.

HuntleyB.

J.

&WalkerB.

H.

(1982)EcologyofTropicalSavanna.

Springer,Heidelburg,Germany.

JacksonP.

C.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,BustamanteM.

,GoldsteinG.

,FrancoA.

,RundelP.

W.

,CaldasL.

S.

,IglerE.

&CausinF.

(1999)Parti-tioningofsoilwateramongtreespeciesinaBrazilianCerradoecosystem.

TreePhysiology36,237–268.

JamesS.

A.

,ClearwaterM.

J.

,MeinzerF.

C.

&GoldsteinG.

(2002)Heatdissipationsensorsofvariablelengthforthemeasurementofsapowintreeswithdeepsapwood.

TreePhysiology22,277–283.

JohnsonD.

M.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,WoodruffD.

R.

&McCullohK.

A.

(2009)Leafxylemembolism,detectedacousticallyandbycryo-SEM,correspondstodecreasesinleafhydraulicconductanceinfourevergreenspecies.

Plant,Cell&Environment32,828–836.

KochG.

W.

,SillettS.

C.

,JenningsG.

M.

&DavisS.

D.

(2004)Thelimitstotreeheight.

Nature428,851–854.

LewisG.

P.

(2005)LegumesoftheWorld.

RoyalBotanicGardens,Kew,Richmond,UK.

LoGulloM.

A.

,NardiniA.

,TriioP.

&SalleoS.

(2003)ChangesinleafhydraulicandstomatalconductancefollowingdroughtstressandirrigationinCeratoniasiliqua(Carobtree).

Physiolo-giaPlantarum117,186–194.

LowmanM.

D.

&HeatwoleH.

(1992)Spatialandtemporalvari-abilityindefoliationofAustralianeucalypts.

Ecology73,129–142.

McDowellN.

,BarnardH.

,BondB.

J.

,etal.

(2002)Therelationshipbetweentreeheightandleafarea:sapwoodarearatio.

Oecologia132,12–20.

McDowellN.

G.

,LicataJ.

&BondB.

J.

(2005)Environmentalsen-sitivityofgasexchangeindifferent-sizedtrees.

Oecologia145,9–20.

MacGregorS.

D.

&O'ConnorT.

G.

(2002)PatchdiebackofColo-phospermummopaneinadysfunctionalsemi-aridAfricansavanna.

AustralEcology27,385–395.

ManionP.

D.

&LachanceD.

(1992)ForestDeclineConcepts.

APSPress,St.

Paul,MN,USA.

MeinzerF.

C.

,RundelP.

W.

,ShariM.

R.

&NilsenE.

T.

(1986)TurgorandosmoticrelationsofthedesertshrubLarreatriden-tata.

Plant,Cell&Environment9,467–475.

MeinzerF.

C.

,GoldsteinG.

,FrancoA.

C.

,BustamanteM.

,IglerE.

,JacksonP.

,CaldasL.

&RundelP.

W.

(1999)AtmosphericandhydrauliclimitationsontranspirationinBrazilianCerradowoodyspecies.

FunctionalEcology13,273–282.

MeinzerF.

C.

,CampanelloP.

I.

,DomecJ.

C.

,GattiM.

G.

,GoldsteinG.

,Villalobos-VegaR.

&WoodruffD.

R.

(2008)ConstraintsonphysiologicalfunctionassociatedwithbrancharchitectureandSize-dependentmortalityinaNeotropicalsavannatree14652009BlackwellPublishingLtd,Plant,CellandEnvironment,32,1456–1466wooddensityintropicalforesttrees.

TreePhysiology28,1609–1617.

MelcherP.

J.

,GoldsteinG.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,YountD.

,JonesT.

,Hol-brookN.

M.

&HuangC.

X.

(2001)WaterrelationsofcoastalandestuarineRhizophoramangle:xylemtensionanddynamicsofembolismformationandrepair.

Oecologia126,182–192.

Mueller-DomboisD.

(1985)Ohi'adiebackandprotectionmanage-mentoftheHawaiianrainforest.

InHawaii'sTerrestrialEcosys-temsPreservationandManagement(edsC.

P.

Stone&J.

M.

Scott)pp.

403–421.

CooperativeNationalParkResourcesStudiesUnit,UniversityofHawaii,Honolulu,HI,USA.

Niinemets,.

(2002)StomatalconductancealonedoesnotexplainthedeclineinfoliarphotosyntheticrateswithincreasingtreeageandsizeinPiceaabiesandPinussylvestris.

TreePhysiology22,515–535.

OliveiraR.

S.

,BezerraL.

,DavidsonE.

A.

,PintoF.

,KlinkC.

A.

,NepstadD.

C.

&MoreiraA.

(2005)DeeprootfunctioninsoilwaterdynamicsincerradosavannasofcentralBrazil.

FunctionalEcology19,574–581.

PiresI.

P.

&MarcatiC.

R.

(2005)AnatomiaeusodamadeiradeduasvariedadesdeSclerolobiumpaniculatumVog.

dosuldoMaranhao,Brazil.

ActaBotanicaBrasilica19,669–678.

PoorterL.

,ZuidemaP.

A.

,Pena-ClarosM.

&BootR.

G.

A.

(2005)Amonocarpictreespeciesinapolycarpicworld:howcanTachigalivasqueziimaintainitselfsosuccessfullyinatropicalrainforestcommunityJournalofEcology93,268–278.

RawitscherF.

(1948)ThewatereconomyofthevegetationofthecamposcerradosinsouthernBrazil.

JournalofEcology36,237–267.

RiceK.

J.

,MatznerS.

L.

,ByerW.

&BrownJ.

R.

(2004)PatternsoftreediebackinQueensland,Australia:theimportanceofdroughtstressandtheroleofresistancetocavitaion.

Oecologia139,190–198.

RyanM.

J.

&YoderB.

J.

(1997)Hydrauliclimitstotreeheightandtreegrowth.

Bioscience47,235–242.

RyanM.

J.

,PhillipsN.

&BondB.

J.

(2006)Thehydrauliclimitationhypothesisrevisited.

Plant,Cell&Environment29,367–381.

SackL.

,CowanP.

D.

,JaikumarN.

&HolbrookN.

M.

(2003)The'hydrology'ofleaves:coordinationofstructureandfunctionintemperatewoodyspecies.

Plant,Cell&Environment26,1343–1356.

SalaA.

&HochG.

(2009)Height-relatedgrowthdeclinesinponderosapinearenotduetocarbonlimitation.

Plant,Cell&Environment32,22–30.

SchferK.

V.

R.

,OrenR.

&TenhunenJ.

D.

(2000)Theeffectoftreeheightoncrownlevelstomatalconductance.

Plant,Cell&Environment23,365–375.

ScholzF.

G.

(2006)Biosicadeltransportedeaguaenelsistemasuelo-planta:redistribucion,resistenciasycapacitanciashidrauli-cas.

PhDthesis,UniversityofBuenosAires,Argentina.

ScholzF.

G.

,BucciS.

J.

,GoldsteinG.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,FrancoA.

C.

&Miralles-WilhelmF.

(2007)Biophysicalpropertiesandfunc-tionalsignicanceofstemwaterstoragetissuesinNeotropicalsavannatrees.

Plant,Cell&Environment30,236–248.

ScholzF.

G.

,BucciS.

J.

,GoldsteinG.

,MoreiraM.

Z.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,DomecJ.

-C.

,VillalobosVegaR.

,FrancoA.

C.

&Miralles-WilhelmF.

(2008)Biophysicalandlifehistorydetermi-nantsofhydraulicliftinNeotropicalsavannatrees.

FunctionalEcology22,773–786.

doi:10.

1111/j.

1365-2435.

2008.

01452.

xSchulteP.

J.

&HinckleyT.

M.

(1985)Acomparisonofpressure–volumecurvedataanalysistechniques.

JournalofExperimentalBotany36,590–602.

StearnsS.

C.

(1992)TheEvolutionofLifeHistoryStrategies.

OxfordUniversityPress,Oxford,UK.

TyreeM.

T.

&HammelH.

T.

(1972)Themeasurementoftheturgorpressureandthewaterrelationsofplantsbythepressure-bombtechnique.

JournalofExperimentalBotany23,267–282.

TyreeM.

T.

&SperryJ.

S.

(1988)DowoodyplantsoperatenearthepointofcatastrophicxylemdysfunctioncausedbydynamicwaterstressPlantPhysiology88,574–580.

TyreeM.

T.

&SperryJ.

S.

(1989)Vulnerabilityofxylemtocavitationandembolism.

AnnualReviewofPlantPhysiologyandPlantMolecularBiology40,19–48.

WattK.

E.

F.

(1987)AnalternativeexplanationfortheincreasedforestmortalityinEuropeandNorthAmerica.

DanskSkov-foreningsTidsskrift72,210–224.

WhiteheadD.

,JarvisP.

G.

&WaringR.

H.

(1984)Stomatalconduc-tance,transpirationandresistancetowateruptakeinaPinussylvestrisspacingexperiment.

CanadianJournalofForestResearch14,692–700.

WilliamsC.

A.

&CooperD.

J.

(2005)Mechanismsofripariancottonwooddeclinealongregulatedrivers.

Ecosystems8,382–395.

WilliamsG.

C.

(1957)Pleiotropy,naturalselectionandtheevolu-tionofsenescence.

Evolution11,398–411.

WoodmanJ.

N.

(1987)Pollution-inducedinjuryinNorthAmericanforests:factsandsuspicions.

TreePhysiology3,1–15.

WoodruffD.

R.

,BondB.

J.

&MeinzerF.

C.

(2004)DoesturgorlimitgrowthintalltreesPlant,Cell&Environment27,229–236.

WoodruffD.

R.

,MccullohK.

A.

,WarrenJ.

M.

,MeinzerF.

C.

&LachenbruchB.

(2007)ImpactsoftreeheightonleafhydraulicarchitectureandstomatalcontrolinDouglas-r.

Plant,Cell&Environment30,559–569.

WoodruffD.

R.

,MeinzerF.

C.

&LachenbruchB.

(2008)Height-relatedtrendsinleafxylemanatomyandshoothydraulicchar-acteristicsinatallconifer:safetyversusefciencyinwatertransport.

NewPhytologist180,90–99.

WoodruffD.

R.

,MeinzerF.

C.

,LachenbruchB.

&JohnsonD.

M.

(2009)Coordinationofleafstructureandgasexchangealongaheightgradientinatallconifer.

TreePhysiology29,261–272.

ZimmermannM.

H.

&JejeA.

A.

(1981)Vessel-lengthdistributionofsomeAmericanwoodyplants.

CanadianJournalofBotany59,1882–1892.

ZwienieckiM.

A.

&HolbrookN.

M.

(1998)Diurnalvariationinxylemhydraulicconductivityinwhiteash(FraxinusamericanaL.

),redmaple(AcerrubrumL.

)andredspruce(PicearubensSarg.

).

Plant,Cell&Environment21,1173–1180.

Received4March2009;receivedinrevisedform20May2009;acceptedforpublication20May20091466Y.

-J.

Zhangetal.

2009BlackwellPublishingLtd,Plant,CellandEnvironment,32,1456–1466

- macroporositycomodo官网相关文档

- Internationalcomodo官网

- scalecomodo官网

- selectscomodo官网

- multicomodo官网

- 7.5comodo官网

- sconocomodo官网

PIGYUN:美国联通CUVIPCUVIP限时cuvip、AS9929、GIA/韩国CN2机房限时六折

pigyun怎么样?PIGYunData成立于2019年,2021是PIGYun为用户提供稳定服务的第三年,目前商家提供香港CN2线路、韩国cn2线路、美西CUVIP-9929、GIA等线路优质VPS,基于KVM虚拟架构,商家采用魔方云平台,所有的配置都可以弹性选择,目前商家推出了七月优惠,韩国和美国所有线路都有相应的促销,六折至八折,性价比不错。点击进入:PIGYun官方网站地址PIGYUN优惠...

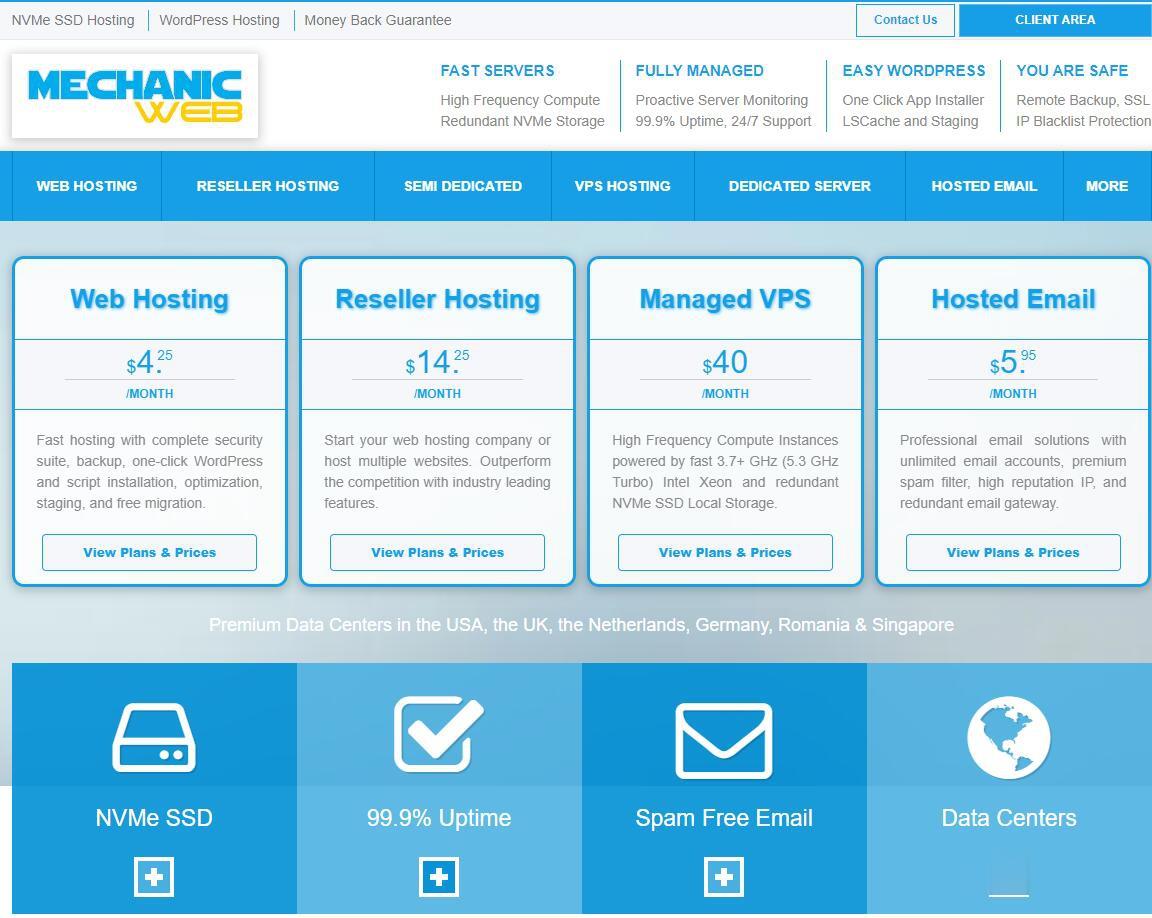

MechanicWeb免费DirectAdmin/异地备份

MechanicWeb怎么样?MechanicWeb好不好?MechanicWeb成立于2008年,目前在美国洛杉矶、凤凰城、达拉斯、迈阿密、北卡、纽约、英国、卢森堡、德国、加拿大、新加坡有11个数据中心,主营全托管型虚拟主机、VPS主机、半专用服务器和独立服务器业务。MechanicWeb只做高端的托管vps,这次MechanicWeb上新Xeon W-1290P处理器套餐,基准3.7GHz最高...

HostYun(月18元),CN2直连香港大带宽VPS 50M带宽起

对于如今的云服务商的竞争着实很激烈,我们可以看到国内国外服务商的各种内卷,使得我们很多个人服务商压力还是比较大的。我们看到这几年的服务商变动还是比较大的,很多新服务商坚持不超过三个月,有的是多个品牌同步进行然后分别的跑路赚一波走人。对于我们用户来说,便宜的服务商固然可以试试,但是如果是不确定的,建议月付或者主力业务尽量的还是注意备份。HostYun 最近几个月还是比较活跃的,在前面也有多次介绍到商...

comodo官网为你推荐

-

租用虚拟主机租用虚拟主机 与 网络空间租赁有什么区别虚拟主机购买虚拟主机需要购买吗?我想自己做个网站,只买了域名了,请问还需要怎么做呢?ip代理地址代理ip地址是怎么来的?香港虚拟空间请大哥帮个忙,介绍可靠的香港虚拟主机?美国网站空间我想买个国外的网站空间,那家好,懂的用过的来说说香港虚拟主机推荐一下香港的虚拟主机公司!100m虚拟主机虚拟主机 100M 和200M 的区别?那个速度快?为什么?虚拟主机管理系统虚拟主机管理系统那一家好?虚拟主机评测麻烦看一下这些虚拟主机商那个好?下载虚拟主机电脑虚拟机怎么弄